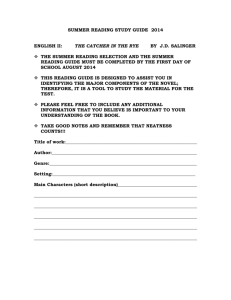

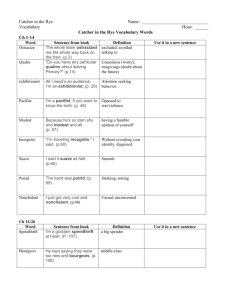

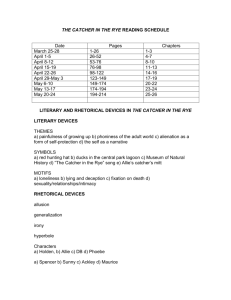

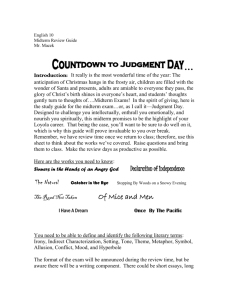

(1960)

advertisement