The Neighborhood Concept: An Evaluation A

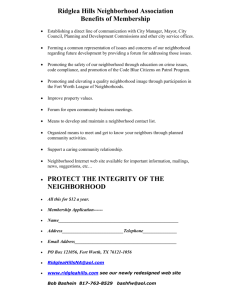

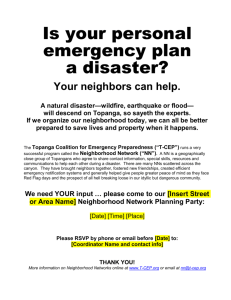

advertisement