American Anthropological Association Annual Meeting 2007

advertisement

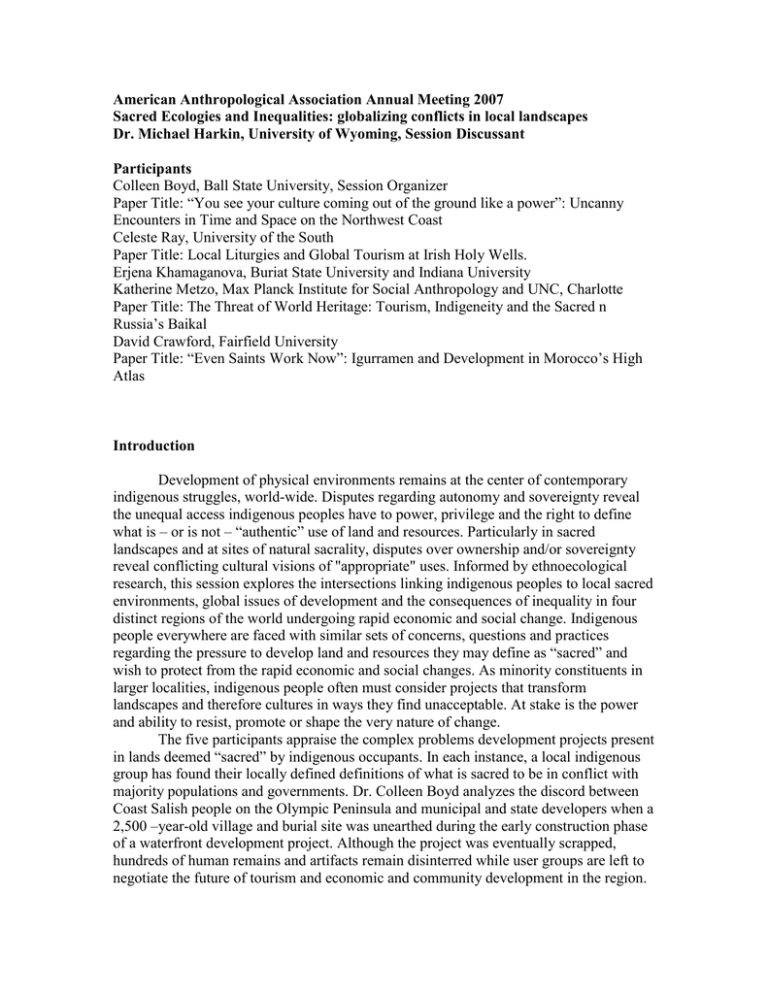

American Anthropological Association Annual Meeting 2007 Sacred Ecologies and Inequalities: globalizing conflicts in local landscapes Dr. Michael Harkin, University of Wyoming, Session Discussant Participants Colleen Boyd, Ball State University, Session Organizer Paper Title: “You see your culture coming out of the ground like a power”: Uncanny Encounters in Time and Space on the Northwest Coast Celeste Ray, University of the South Paper Title: Local Liturgies and Global Tourism at Irish Holy Wells. Erjena Khamaganova, Buriat State University and Indiana University Katherine Metzo, Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology and UNC, Charlotte Paper Title: The Threat of World Heritage: Tourism, Indigeneity and the Sacred n Russia’s Baikal David Crawford, Fairfield University Paper Title: “Even Saints Work Now”: Igurramen and Development in Morocco’s High Atlas Introduction Development of physical environments remains at the center of contemporary indigenous struggles, world-wide. Disputes regarding autonomy and sovereignty reveal the unequal access indigenous peoples have to power, privilege and the right to define what is – or is not – “authentic” use of land and resources. Particularly in sacred landscapes and at sites of natural sacrality, disputes over ownership and/or sovereignty reveal conflicting cultural visions of "appropriate" uses. Informed by ethnoecological research, this session explores the intersections linking indigenous peoples to local sacred environments, global issues of development and the consequences of inequality in four distinct regions of the world undergoing rapid economic and social change. Indigenous people everywhere are faced with similar sets of concerns, questions and practices regarding the pressure to develop land and resources they may define as “sacred” and wish to protect from the rapid economic and social changes. As minority constituents in larger localities, indigenous people often must consider projects that transform landscapes and therefore cultures in ways they find unacceptable. At stake is the power and ability to resist, promote or shape the very nature of change. The five participants appraise the complex problems development projects present in lands deemed “sacred” by indigenous occupants. In each instance, a local indigenous group has found their locally defined definitions of what is sacred to be in conflict with majority populations and governments. Dr. Colleen Boyd analyzes the discord between Coast Salish people on the Olympic Peninsula and municipal and state developers when a 2,500 –year-old village and burial site was unearthed during the early construction phase of a waterfront development project. Although the project was eventually scrapped, hundreds of human remains and artifacts remain disinterred while user groups are left to negotiate the future of tourism and economic and community development in the region. Similarly, Dr. Katherine Metzo and Ms. Erjena Khamaganova, Ph.C. explore plans to turn Russia’s Baikal region into a “free economic zone.” The dominant form of development will likely be tourism. This raises concerns for local peoples about crossing boundaries between ritual and sacred practices and what will ultimately be offered to tourists for public ‘consumption.’ Dr. Celeste Ray examines the impact of economic development and tourism on Irish holy wells. Recent agricultural reforms in Ireland have resulted in the destruction of many wells. Furthermore, the increasing presence of international spiritual tourists and neopagans contests the sacrality and community ownership of these numinous landscapes. Family stewards of particular sites worry that "inappropriate" visits and rituals may cause wells to loose their thaumaturgical power, yet pressures to support local developing economies makes resistance difficult to fully realize. Finally, Dr. David Crawford, Fairfield University, considers the contemporary struggles of Morocco’s famous “Saints of the Atlas.” With their traditional role as conflict mediators usurped by the state, and their pastures seized as eco-tourist destinations, saintly lineages of the High Atlas have been left behind in terms of economic development and educational opportunities. In a globalizing era, the traditions of saintly lineages are becoming a social liability.