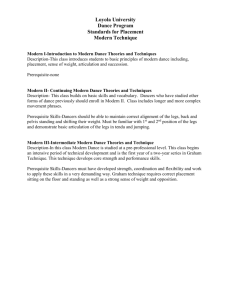

1 USER A by

advertisement