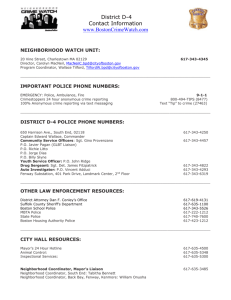

1962 by SCOTT -

advertisement