Last Time CSE 486/586 Distributed Systems Logical Time •

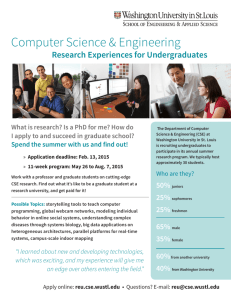

advertisement

Last Time • Clock skews do happen • Cristian’s algorithm – One server – Server-side timestamp and one-way delay estimation CSE 486/586 Distributed Systems Logical Time • NTP (Network Time Protocol) – Hierarchy of time servers – Estimates the actual offset between two clocks – Designed for the Internet Steve Ko Computer Sciences and Engineering University at Buffalo CSE 486/586 CSE 486/586 2 Then a Breakthrough… Basics: State Machine • We cannot sync multiple clocks perfectly. • Thus, if we want to order events happened at different processes (remember the ticket reservation example?), we cannot rely on physical clocks. • Then came logical time. • State: a collection of values of variables • Event: an occurrence of an action that changes the state, (i.e., instruction, send, and receive) • As a program, – We can think of all possible execution paths. – First proposed by Leslie Lamport in the 70’s – Based on causality of events – Defined relative time, not absolute time S0 • At runtime, – There’s only one path that the program takes. S1 • Equally applicable to • Critical observation: time (ordering) only matters if two or more processes interact, i.e., send/receive messages. – A single process – A distributed set of processes S2 S3 S4 SF CSE 486/586 CSE 486/586 3 Ordering Basics 4 Abstract View p1 • Why did we want to synchronize physical clocks? • What we need: Ordering of events. • Arises in many different contexts… a b m1 Phy si cal Physical titime me p2 c d m2 p3 e f • Above is what we will deal with most of the time. • Ordering question: what do we ultimately want? – Taking two events and determine which one happened before the other one. CSE 486/586 C 5 CSE 486/586 6 1 What Ordering? Lamport Timestamps p1 a b m1 Phy si cal Physical titime me p2 c d m2 p1 1 2 a b m1 p2 p3 e f • Ideal? p3 – Perfect physical clock synchronization 3 4 c d Phy sical Physical titime me m2 1 5 e f • Reliably? – Events in the same process – Send/receive events CSE 486/586 CSE 486/586 7 8 Logical Clocks CSE 486/586 Administrivia • • PA2 is out. Two points: Lamport algorithm assigns logical timestamps: • All processes use a counter (clock) with initial value of zero • A process increments its counter when a send or an – Multicast: Just create 5 connections (5 sockets) and send a message 5 times through different connections. – ContentProvider: Don’t call it directly. Don’t share anything with the main activity. Consider it an almost separate app only accessible via ContentResolver. instruction happens at it. The counter is assigned to the event as its timestamp. • A send (message) event carries its timestamp • For a receive (message) event the counter is updated by • Please pay attention to your coding style. • Please participate in our survey (not related to class, but still :-) max(local clock, message timestamp) + 1 • Define a logical relation happened-before (→) among events: – http://goo.gl/forms/nwFgf3niFW – We’re designing a new photo storage/programming framework for mobile devices. • On the same process: a → b, if time(a) < time(b) • If p1 sends m to p2: send(m) → receive(m) • (Transitivity) If a → b and b → c then a → c • Shows causality of events CSE 486/586 CSE 486/586 9 Find the Mistake: Lamport Logical Time Corrected Example: Lamport Logical Time Physical Time p 1 p 2 p 3 p 4 n 0 1 1 0 Physical Time 2 2 0 3 3 3 p 2 6 8 5 4 7 5 6 7 1 0 p 3 0 p 4 0 n 2 7 11 2 2 3 3 8 8 3 6 4 9 10 5 4 7 5 6 7 Clock Value timestamp Message CSE 486/586 0 1 Clock Value timestamp C p 1 6 4 0 4 4 3 2 10 Message CSE 486/586 12 2 One Issue Vector Timestamps • With Lamport clock Physical Time • e “happened-before” f ⇒ timestamp(e) < timestamp (f), but p 2 0 1 1 0 p 3 0 p 1 p 4 2 2 7 3 • Each process learns about what happened in all others. 9 10 5 4 0 • Each process keeps a separate clock & pass them around. 6 4 3 • Idea? 8 3 2 • timestamp(e) < timestamp (f) ⇒ X e “happened-before” f 8 (1,0,0) (2,0,0) p1 7 5 6 a b 7 m1 (2,1,0) n Clock Value timestamp Message p2 3 and 7 are logically concurrent events Physical Phy sical titime me m2 (2,2,2) e f CSE 486/586 13 Vector Logical Clocks d (0,0,1) p3 CSE 486/586 (2,2,0) c 14 Find a Mistake: Vector Logical Time • Vector Logical time addresses the issue: • All processes use a vector of counters (logical clocks), ith Physical Time element is the clock value for process i, initially all zero. • Each process i increments the ith element of its vector upon an instruction or send event. Vector value is timestamp of the event. • A send(message) event carries its vector timestamp (counter vector) • For a receive(message) event, Vreceiver[j] = • Max(Vreceiver[j] , Vmessage[j]), if j is not self, • Vreceiver[j] + 1, otherwise p 1 0,0,0,0 p 2 0,0,0,0 4,0,2,2 3,0,2,2 0,0,0,0 p 4 0,0,0,0 (4,0,2,2) 1,2,0,0 1,1,0,0 (2,0,0,0) 2,0,1,0 (1,2,0,0) (2,0,2,2) 2,0,2,0 2,2,3,0 (2,0,2,0) 2,0,2,1 2,0,2,2 4,2,4,2 4,2,5,3 (2,0,2,3) 2,0,2,3 Vector logical clock (vector timestamp) • You update your own clock. For all other clocks, rely on what 2,0,0,0 (1,0,0,0) p 3 n,m,p,q • Key point 1,0,0,0 Message other processes tell you and get the most up-to-date values. CSE 486/586 Comparing Vector Timestamps The Use of Logical Clocks • VT1 = VT2, • Is a design decision • NTP error bound • iff VT1[i] = VT2[i], for all i = 1, … , n • iff VT1[i] <= VT2[i], for all i = 1, … , n • If your system doesn’t care about this inaccuracy, then NTP should be fine. • Logical clocks impose an arbitrary order over concurrent events anyway • VT1 < VT2, • iff VT1 <= VT2 & ∃ j (1 <= j <= n & VT1[j] < VT2 [j]) • VT1 is concurrent with VT2 • iff (not VT1 <= VT2 AND not VT2 <= VT1) CSE 486/586 16 – Local: a few ms – Wide-area: 10’s of ms • VT1 <= VT2, C CSE 486/586 15 – Breaking ties: process IDs, etc. 17 CSE 486/586 18 3 Summary Acknowledgements • Relative order of events enough for practical purposes • These slides contain material developed and copyrighted by Indranil Gupta at UIUC. – Lamport’s logical clocks – Vector clocks • Next: How to take a global snapshot CSE 486/586 C 19 CSE 486/586 20 4