E PLANNING PROCESSES AT LEVELS B.S., Rutgers

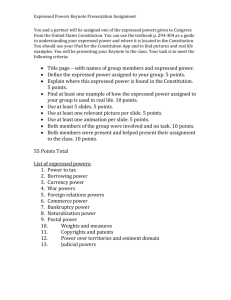

advertisement