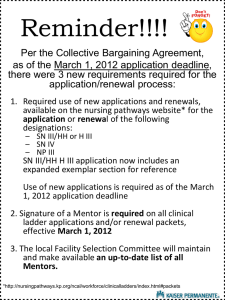

CONTEXT: E. , REQUIREMENTS

advertisement