JU20 2 Spatialities of Conflict:

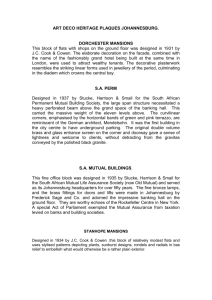

advertisement