Helicodiscus salmonaceus Common Name: Salmon Coil Phylum: Mollusca

advertisement

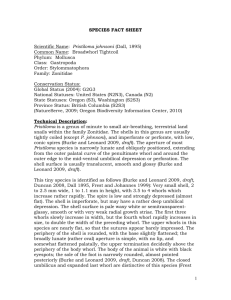

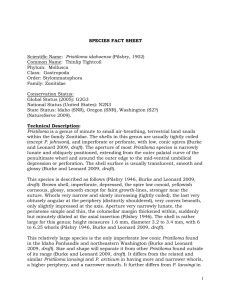

SPECIES FACT SHEET Scientific Name: Helicodiscus salmonaceus Hemphill, 1890 Common Name: Salmon Coil Phylum: Mollusca Class: Gastropoda Order: Stylomatophora Superfamily: Punctoidea Family: Helicodiscidae Conservation Status: Global Status (2006): G2- Imperiled State Status: Washington (S2S3 – Imperiled/Vulnerable), Idaho (SNRState Not Ranked), Oregon (not yet listed). (NatureServe 2010). Technical Description: Helicodiscus is a genus of air-breathing, terrestrial pulmonate snails in the superfamily Punctoidea and family Helicodiscidae (Bouchet et al. 2005). Most, if not all, North American members of this family, have white bodies with unpigmented eyestalks, and are probably blind (USFWS 1983). This very small, unique discoidal species is described as follows (Burke and Leonard 2009, draft): The shell measures 4.3 to 5 mm wide by 1.3 to 1.8 mm high, with 5 to 5.5 whorls. The umbilicus is wide and dished, measuring about half the width of the shell. The shell color is translucent, whitish, or with a horn-colored tint. The spire is flat and discoidal. Individual whorls are of small diameter and increase very slowly so that even though they grow to the outer edge of the previous whorl, the width of the last whorl is little greater than that of the penultimate. The periphery is rounded, and the aperture small, narrowly lunate, and only slightly oblique. There are paired apertural teeth which are often farther back inside the shell, or there may even be more than one pair spaced back around the inside of the whorl. The shell sculpture is of raised spiral threads (lirae) running parallel with the whorls. There are no other species native to the Pacific Northwest which could be reasonably confused with this species (Burke and Leonard 2009, draft). A photograph of this species is provided in the appendix (Attachment 4). Life History: Most pulmonate landsnails are hermaphroditic (sharing a common single male and female gonad organ). Eggs and sperm often develop at different times within the individual such that self-fertilization is uncommon (Nordsieck 2010). Once fertilized, the egg develops into a veliger larval stage, found inside of the egg. When the veliger matures, a fully formed juvenille snail emerges from the egg (Nordsieck 2010). The related Helicodiscus parallelus is reported to lay one to two eggs per clutch 1 (USFWS 1983), although specific details regarding the reproduction and egg-laying habits of H. salmonaceus are unknown. Specific dietary requirements of this species are not reported, but other members of the Helicodiscid family possess radula with numerous small teeth specialized for scraping fungi, algae, and plant cells off surfaces where they graze (USFWS 1983). Range, Distribution, and Abundance: This species occurs in southeastern Washington, northeastern Oregon, and the Idaho Panhandle. Records span from Spokane, Washington and Cataldo, Idaho south to Asotin County, Washington; Wallowa County, Oregon; and Idaho County, Idaho (Burke 2009, pers. comm., Jepsen et al. 2010). It is the most widespread of the smaller land snail species in the Lower Salmon River Drainage, Idaho (Nez Perce National Forest area), where it is known from 34 sites and has long been regarded as characteristic of the area (Frest and Johannes 1997, Hendricks and Maxell 2005). In Washington, it is known from Spokane, Whitman, and Asotin Counties. In Oregon, it is known only from a recently surveyed site in Wallowa County (Jepsen et al. 2010). BLM/Forest Service land: This species is documented on BLM land in the Vale-Washington and Vale-Oregon Districts. It is suspected on BLM land in the Spokane District, and on the Umatilla National Forest. Abundance: No information is available. Habitat Associations: This xerophilic species is found in dry rocky habitats, often intermixed with sage brush and grasses. Known records are from talus; rocky rubble at the base of large boulders; rocky soil with grass and shrubs; talus and basalt cliff areas; and under rocks in a rock pile (Leonard 2009, pers. comm., Deixis 2009, Burke 2009, pers. comm., Jepsen et al. 2010). Reported elevations are from 733 to 1028 feet. At the Idaho sites, it inhabits taluses or rock outcrops at low to moderate elevations, typically at comparatively dry, open sites with sage scrub (Frest and Johannes 1997). The recent Oregon record is from talus on a north facing slope among Douglas fir, Ponderosa pine, and Rocky Mountain maple, with Pacific ninebark and bunchgrasses in the understory (Jepsen et al. 2010). Rather widespread in distribution, this species is considered limited by the occurrence of its rocky habitat (Burke 2009, pers. comm.). Helicodiscus salmonaceus is commonly associated with Cryptomastix (Cryptomastix) harfordiana, Oreohelix haydeni perplexa, and other Oreohelix species (Frest and Johannes 1995). In Oregon, it has recently 2 been found co-occuring with Cryptomastix magnidentata, Cryptomastix populi (Oregon Sensitive), Cochlicopa lubrica, Deroceras reticulatum, Pupila hebes, Hawaiia minuscula, Vallonia cyclophorella, and Vitrina pelucida (Jepsen et al. 2010). Threats: Although limited, the habitat of this species is probably not highly threatened (Burke 2011, pers. comm.). Road building is considered the main threat (Burke 2011, pers. comm.), along with any other activities that disturb the terrain structure, litter composition/abundance, or moisture levels. Spraying of herbicide/insecticides may also be of concern. Climate change may pose an additional threat in this region. Conservation Considerations: Inventory: Because there are so few records of this species in Oregon and Washington, knowledge of additional sites are needed to better determine and monitor its distribution (Burke 2011, pers. comm.). Surveys should focus on uncovering new populations within the expected range of this species (Johannes 2009, pers. comm.). Since there are a large number of rocky terrestrial habitats in southeastern Washington and northeastern Oregon that haven’t been surveyed for snails, this species is probably not as scarce as believed, and there is a high likelihood of encountering it during additional surveys (Burke 2009, pers. comm.). This species is expected to occur in Hells Canyon, Oregon, since it is known from the Snake River in Asotin Co., Washington, where the habitat is essentially the same (Burke 2011, pers. comm.). Additional sites are also expected in the channeled scablands of southeastern Washington (Burke 2011, pers. comm.). Management: Consider managing existing and potential sites to reduce the impacts of road building, tree harvest, recreational activity, development, construction activities, and other practices that may adversely affect this species and its habitat. Prepared by: Sarah Foltz Jordan Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation Date: July 2011 Edited by: Sarina Jepsen Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation Date: August 2011 Final Edits by: Rob Huff Conservation Planning Coordinator, FS/BLM Date: August 2011 3 ATTACHMENTS: (1) References (2) List of pertinent or knowledgeable contacts (3) Map of known records in Oregon and Washington (4) Photograph of live adult (5) Terrestrial Gastropod Survey Protocol, including specifics for this species ATTACHMENT 1: References: Bouchet, P., Rocroi, J.-P., Frýda, J., Hausdorf, B., Ponder, W., Valdés, Á. and A. Warén. 2005. Classification and nomentclator of gastropod families. Malacologia 47(1-2): 1–397. Burke, T. and W. Leonard. 2009. Land Mollusks of the Pacific Northwest United States. In preparation. Burke, Tom. 2009. Personal communication with Sarah Foltz Jordan, Xerces Society. Burke, Tom. 2011. Personal communication with Sarah Foltz Jordan, Xerces Society. Deixis MolluscDB database. 2009. An unpublished collection of mollusk records maintained by Ed Johannes. Dunk, J. R., Zielinski, W. J., West, K., Schmidt, K., Baldwin, J., Perrochet, J., Schlick, K., and J. Ford. 2002. Distributions of rare mollusks relative to reserved lands in northern California. Northwest Science 76: 249–256. Frest, T. J. and E. J. Johannes. 1995. Interior Columbia Basin mollusk species of special concern. Final report: Interior Columbia Basin Ecosystem Management Project, Walla Walla, WA. Contract #43-0E00-49112. 274 pp. plus appendices. Frest, T. J. and E. J. Johannes. 1997. Land snail survey of the Lower Salmon River Drainage, Idaho. Idaho Bureau of Land Management. Technical Bullinton No. 97-18. Available at: http://www.blm.gov/pgdata/etc/medialib/blm/id/publications/technic al_bulletins/tb_97-18. (Accessed 23 May 2009). Hendricks, P. and B. A. Maxell. 2005. USFS Northern Region 2005 land mollusk inventory: a progress report. Report submitted to the U.S. Forest 4 Service Region 1. Montana Natural Heritage Program (Agreement #05CS-11015600-033, Helena, Montana. 52 pp. Available at: http://www.fs.fed.us/r1/projects/wildlifeecology/USFS_R1_Mollusk_Progress_Report_12_31_05.pdf (Accessed 27 July 2011). Johannes, Ed. 2009. Personal communication with Sarah Foltz Jordan, Xerces Society. Jepsen, S., Burke, T., and S. F. Jordan. 2011. Final Report to the Interagency Special Status / Sensitive Species Program regarding Surveys for four terrestrial mollusk species on the Umatilla National Forest and Vale District BLM lands. Report submitted by The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. Leonard, William. 2009. Personal communication with Sarah Foltz Jordan, Xerces Society. NatureServe. 2010. “Helicodiscus salmonaceus”. Version 7.1 (2 February 2009). Data last updated: August 2010. Available at: www.natureserve.org/explorer (Accessed 27 July 2011). Nordsieck, R. 2010. “The reproduction of Gastropods”. Available at: http://www.molluscs.at/gastropoda/morphology/reproduction.html (Accessed 27 July 2011). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). 1983. Virginia fringed mountain snail (Polygyriscus virginianus) recovery plan. Prepared by Region 5 Fish and Wildlife Service. 16 pp. plus appendices. ATTACHMENT 2: List of pertinent or knowledgeable contacts. Tom Burke, regional expert, Washington. William Leonard, regional expert, Washington. Ed Johannes, Deixis Consultants, Seattle-Tacoma, Washington. 5 ATTACHMENT 3: Map of known records in Oregon and Washington Records of Helicodiscus salmonaceus in Washington and Oregon, relative to Forest Service and BLM lands. Idaho records are not shown. 6 ATTACHMENT 4: Photograph of live adult. Helicodiscus salmonaceus live adult. Photograph by William Leonard, used with permission. ATTACHMENT 5: Terrestrial Gastropod Survey Protocol, including specifics for this species: Survey Protocol Taxonomic group: Gastropoda Please refer to the following documents for detailed mollusk survey methodology: 1. General collection and monitoring methods for aquatic and terrestrial mollusks (pages 64-71): Frest, T.J. and E.J. Johannes. 1995. Interior Columbia Basin mollusk species of special concern. Final report: Interior Columbia Basin Ecosystem Management Project, Walla Walla, WA. Contract #43-0E00-4-9112. 274 pp. plus appendices. 7 2. Pre-disturbance surveys for terrestrial mollusk species, the objective of which is to establish whether a specific mollusk is present in proposed project areas with a reasonable level of confidence, and to document known sites discovered during surveys: Duncan, N., Burke, T., Dowlan, S. and P. Hohenlohe. 2003. Survey protocol for survey and manage terrestrial mollusk species from the Northwest Forest Plan. Version 3.0. U.S. Department of Interior, Bureau of Land Management, Oregon/Washington and U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Region 6, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 70 pp. [Available on ISSSSP intranet site]. 3. Inventory report including standard data forms for terrestrial mollusk site surveys: Hendricks, P. and B. A. Maxell. 2005. USFS Northern Region 2005 land mollusk inventory: a progress report. Report submitted to the U.S. Forest Service Region 1. Montana Natural Heritage Program (Agreement #05-CS-11015600-033, Helena, Montana. 52 pp. Available at: http://www.fs.fed.us/r1/projects/wildlifeecology/USFS_R1_Mollusk_Progress_Report_12_31_05.pdf (Accessed 27 July 2011). Species-specific Survey Details: Helicodiscus salmonaceus This species is known from southeastern Washington, northeastern Oregon, and the Idaho Panhandle. Because there are so few records from Oregon and Washington, knowledge of additional sites would be useful to better determine and monitor its distribution (Burke 2011, pers. comm.). Surveys should focus on uncovering new populations within the expected range of this species (Johannes 2009, pers. comm.). Since there are a large number of rocky terrestrial habitats in southeastern Washington and northeastern Oregon that haven’t been surveyed for snails, this species is probably not as scarce as believed, and there is a high likelihood of encountering it during additional surveys (Burke 2009, pers. comm.). This species is expected to occur in Hells Canyon, Oregon, since it is known from the Snake River in Asotin Co., Washington, where the habitat is essentially the same (Burke 2011, pers. comm.). Additional sites are also expected in the channeled scablands of southeastern Washington (Burke 2011, pers. comm.). 8 Helicodiscus salmonaceus is considered limited by the occurrence of talus and other rocky habitat (Burke 2008, pers. comm.). At the Idaho sites, it inhabits taluses or rock outcrops at low to moderate elevations, typically at comparatively dry, open sites with sage scrub (Frest and Johannes 1997). In Washington, specimens have been found in talus, rocky rubble at the base of large boulders, rocky soil with grass and shrubs, talus and basalt cliff areas, and under rocks in a rock pile (Leonard 2009, pers. comm., Deixis 2009, Burke 2009, pers. comm., Jepsen et al. 2010). The recent Oregon record is from talus on a north facing slope among Douglas fir, Ponderosa pine, and Rocky Mountain maple, with Pacific ninebark and bunchgrasses in the understory (Jepsen et al. 2010). Reported elevations are from 733 to 1028 feet. Like other terrestrial snails in the Interior Columbia Basin, this species is best surveyed during spring and fall, when the weather is most suitable (cool and moist) for finding active snails and slugs. A general Forest Service survey protocol for terrestrial land snails recommends surveys be conducted only at temperatures greater than 5 °C and when the soil is moist to the touch (Dunk et al. 2002). Frest and Johannes (1995) recommend surveys in this region from April to May, after spring melt-out, or from September to November, as fall-winter rains occur but before the first heavy freeze. Known records for this species (shells and live adults) are from late March to June, and from late August to early October. Hand collection in the appropriate habitat is the recommended survey method for this species (Deixis MolluscDB 2009). Although not abundant, it is not hard to find where it occurs (Burke 2008, pers. comm.). This species was recently encountered at three localities in Oregon and Washington using the following terrestrial mollusk survey methods (Jepsen et al. 2010): Survey areas were visited in September, after the region had received a few days of heavy rain. Key habitat features known to be utilized by the target species (e.g., talus slopes or basalt outcrops) were searched for while driving or hiking in a selected area. Promising areas were surveyed by turning over and examining the undersides of rocks and/or dead wood. Vegetation was also examined. Hand rakes were used for moving talus and to aid in searching. Hand lenses aided identification in the field. A GPS unit recorded geographic coordinates for each site surveyed. A minimum of 20 minutes search time was spent at each site, although the total time spent at each site varied based on findings. If 20‐30 minutes were spent searching for mollusks without finding 9 additional species during that time period, surveyors moved on to a new site. When mollusks were observed, voucher specimens (shells and live snails) were collected in small vials or recycled yogurt containers and kept in a cooler with ice. In the evening, small snails were placed directly in 70% ethanol, whereas large snails were drowned overnight in water (causing them to emerge from their shells) and then stored in 70% ethanol. Identification of this species is based on external shell morphology, as outlined in the fact sheet. Expert identification is recommended. 10