OF: USE NEIGHBORHOODS BY MOTHERS

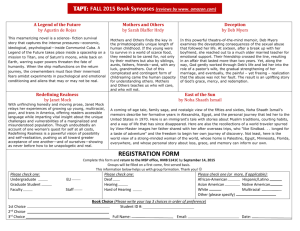

advertisement