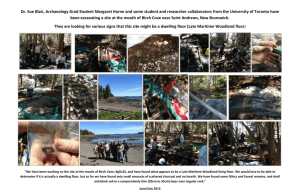

by Bachelor of Science in Environmental Design

advertisement