Document 10546577

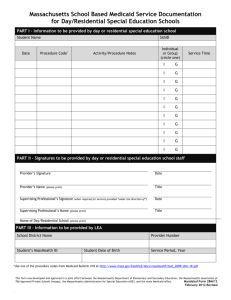

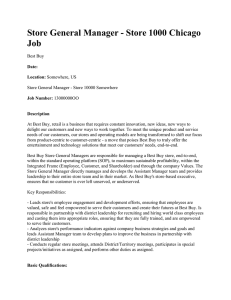

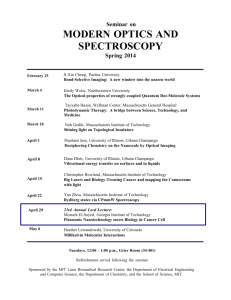

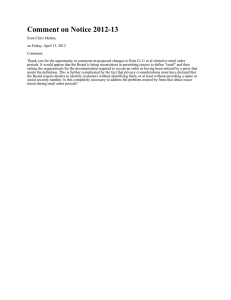

advertisement