Transit as a catalyst for urban revitalization:

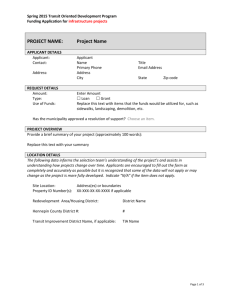

advertisement