Document 10544378

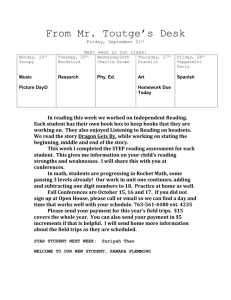

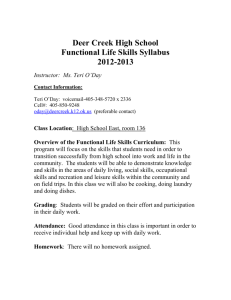

advertisement