CAN EVERYBODY WIN? KINGSTON by

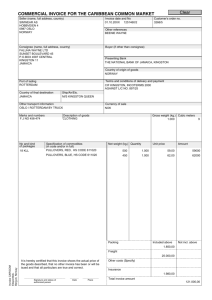

advertisement