by Johannes Karl Dietrich Garbrecht

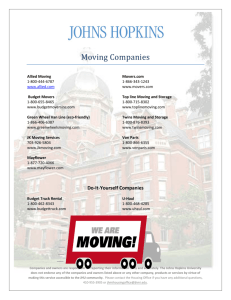

advertisement