Document 10532319

advertisement

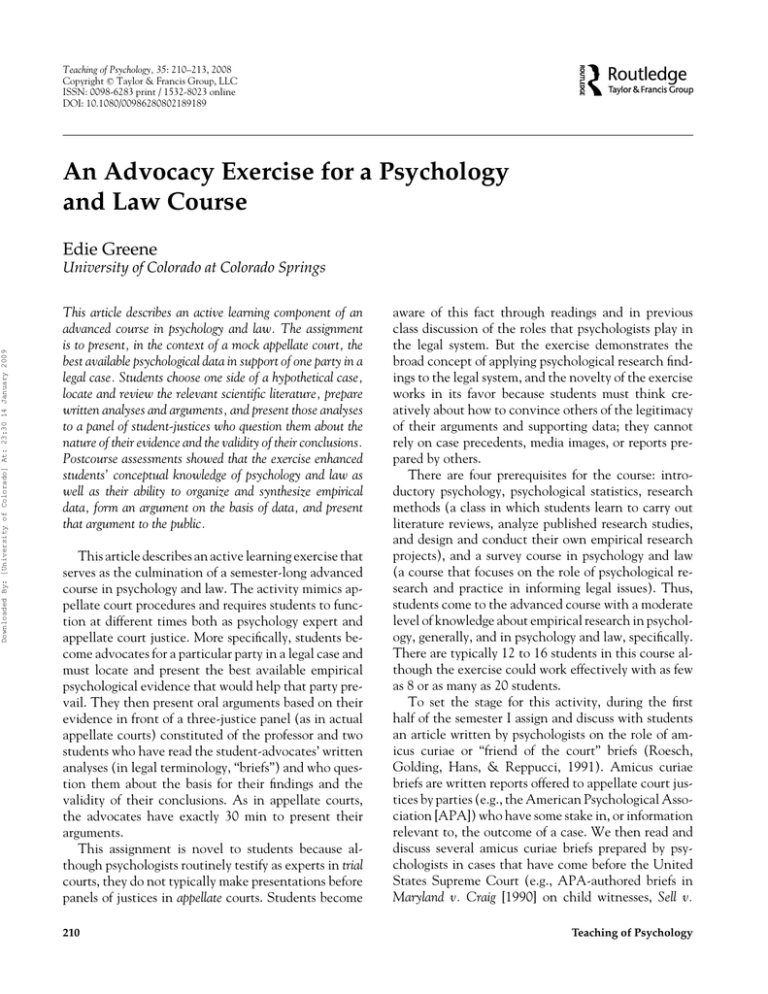

Teaching of Psychology, 35: 210–213, 2008 C Taylor & Francis Group, LLC Copyright ISSN: 0098-6283 print / 1532-8023 online DOI: 10.1080/00986280802189189 An Advocacy Exercise for a Psychology and Law Course Edie Greene Downloaded By: [University of Colorado] At: 23:30 14 January 2009 University of Colorado at Colorado Springs This article describes an active learning component of an advanced course in psychology and law. The assignment is to present, in the context of a mock appellate court, the best available psychological data in support of one party in a legal case. Students choose one side of a hypothetical case, locate and review the relevant scientific literature, prepare written analyses and arguments, and present those analyses to a panel of student-justices who question them about the nature of their evidence and the validity of their conclusions. Postcourse assessments showed that the exercise enhanced students’ conceptual knowledge of psychology and law as well as their ability to organize and synthesize empirical data, form an argument on the basis of data, and present that argument to the public. This article describes an active learning exercise that serves as the culmination of a semester-long advanced course in psychology and law. The activity mimics appellate court procedures and requires students to function at different times both as psychology expert and appellate court justice. More specifically, students become advocates for a particular party in a legal case and must locate and present the best available empirical psychological evidence that would help that party prevail. They then present oral arguments based on their evidence in front of a three-justice panel (as in actual appellate courts) constituted of the professor and two students who have read the student-advocates’ written analyses (in legal terminology, “briefs”) and who question them about the basis for their findings and the validity of their conclusions. As in appellate courts, the advocates have exactly 30 min to present their arguments. This assignment is novel to students because although psychologists routinely testify as experts in trial courts, they do not typically make presentations before panels of justices in appellate courts. Students become 210 aware of this fact through readings and in previous class discussion of the roles that psychologists play in the legal system. But the exercise demonstrates the broad concept of applying psychological research findings to the legal system, and the novelty of the exercise works in its favor because students must think creatively about how to convince others of the legitimacy of their arguments and supporting data; they cannot rely on case precedents, media images, or reports prepared by others. There are four prerequisites for the course: introductory psychology, psychological statistics, research methods (a class in which students learn to carry out literature reviews, analyze published research studies, and design and conduct their own empirical research projects), and a survey course in psychology and law (a course that focuses on the role of psychological research and practice in informing legal issues). Thus, students come to the advanced course with a moderate level of knowledge about empirical research in psychology, generally, and in psychology and law, specifically. There are typically 12 to 16 students in this course although the exercise could work effectively with as few as 8 or as many as 20 students. To set the stage for this activity, during the first half of the semester I assign and discuss with students an article written by psychologists on the role of amicus curiae or “friend of the court” briefs (Roesch, Golding, Hans, & Reppucci, 1991). Amicus curiae briefs are written reports offered to appellate court justices by parties (e.g., the American Psychological Association [APA]) who have some stake in, or information relevant to, the outcome of a case. We then read and discuss several amicus curiae briefs prepared by psychologists in cases that have come before the United States Supreme Court (e.g., APA-authored briefs in Maryland v. Craig [1990] on child witnesses, Sell v. Teaching of Psychology Downloaded By: [University of Colorado] At: 23:30 14 January 2009 U.S., 2003, on forced medication of mentally ill offenders and competence to stand trial, Lockhart v. McCree, 1986, on death-qualified juries in death penalty cases, and Harris v. Forklift Systems, Inc., 1993, on sexual harassment). These briefs are available online at http://www.apa.org/psyclaw/amicus.html. After reading and discussing the briefs, students prepare their own amicus curiae briefs, adhering carefully to the format and style of the briefs they read. Just prior to midsemester, I present written details of 6 to 10 fictitious cases, depending on the number of students enrolled. (I offer half the number of cases as students enrolled.) By lottery, students choose the case they will argue and the side they will represent from among the descriptions that I provide. Thus, only two advocates present each case, and each student has a unique assignment. All the cases are hypothetical but based on controversial issues that have been litigated and for which empirical psychological research data exist. I choose issues about which students can make reasonable arguments, based on empirical research, for either side. Over the years, the topics have concerned sexual predator statutes and predictions of sex offender recidivism, conflicting rights in adoption cases, the effects of statutes that require parental notification prior to abortion, relocation of children after a divorce, and the consequences of drug testing for pregnant women, among others. The case descriptions direct students to focus on specific issues in the controversy. I provide details of one such case in Table 1. For this case, one student would locate, synthesize, and write about the empirical evidence in support of the validity of repressed memories (e.g., Williams, 1994), and another student would argue for the existence of false memories (e.g., Mazzoni & Memon, 2003). Students have 3 to 6 weeks to survey the literature, construct their arguments, and prepare their written amicus curiae briefs. (The variable length of time is related to the fact that oral arguments occur during the last few weeks of the semester—at a rate of approximately two cases per 3-hr class session—and students provide copies of their written briefs to me and all classmates 1 week prior to their scheduled oral arguments.) Written amicus curiae briefs are typically between 12 and 15 pages in length, excluding references. By the following week, the students and I have read these briefs as well as background articles chosen by the advocates. Then, just prior to oral arguments, I randomly select two students from the class to join me Vol. 35, No. 3, 2008 Table 1. Case Facts in Green v. Gold on the Reliability of Repressed Memories Charles Green, the plaintiff/appellant, alleged severe physical, sexual, and psychological abuse by a priest, Father Bernard Gold, the defendant/respondent, at a parochial high school during the 1960s and 1970s. Green claims that to avoid the pain of the abuse, his memory of the events was repressed. The memories began to reappear in 1999. In 2002, he sued the priest, the school, the archdiocese, and the archbishop. In a previous trial, the judge ruled in favor of the defendant on the grounds that the statute of limitations on the plaintiff’s claim had expired. (According to the applicable law, the “date of wrong” is when the plaintiff knew or should have known that harm had been done to him, and he had 3 years beyond that point to file suit.) Charles Green now appeals that decision. He argues that his memories were repressed, rather than forgotten. Thus, the court should use the delayeddiscovery rule, which was developed for cases that involved belated awareness of harm, to begin the statute of limitations at the time the abuse memories were recovered. The question for oral argument concerns the reliability of so-called repressed memories. The plaintiff, Green, contends that repression exists apart from the normal process of forgetting and that there is scientifically valid evidence documenting the existence of repressed memories in situations of abuse. The defendant, Gold, argues that the 3-year statute of limitations should apply because scientific evidence suggests that repressed memories are indistinguishable from forgotten memories and because of documented instances of false memories of child sexual abuse. as appellate justices. Our task is to pose questions to the advocates as in actual appellate courts. This assignment requires that all class members become familiar with the topic and the research data on which each advocate relies, think critically about the arguments advanced in the amicus curiae briefs, and prepare questions for the advocates prior to class. With random selection of judges, students do not know, prior to class time, whether they will serve as judges that day so all must come to class fully prepared. I grade students on their performance as appellate judges (in particular, on the number and insightfulness of their questions) as well as on their own amicus curiae briefs and oral arguments. Early in the semester I provide a rubric that outlines grading criteria for each of these tasks. Impact on Teaching and Learning I have evaluated changes in students’ knowledge of some core concepts in psychology and law as well 211 Table 2. Students’ Mean Self-Reported Assessments and Standard Deviations, Precourse and Postcourse Precourse Item Organize a large amount of research material Form and support an opinion on the basis of research Speak in public for 30 min while being interrupted Postcourse M SD M SD p 6.18 6.72 5.55 1.47 1.35 1.97 8.27 8.91 8.18 1.19 1.14 1.08 <.01 <.01 <.01 Downloaded By: [University of Colorado] At: 23:30 14 January 2009 Note. Response options ranged from 1 (no ability) to 10 (extensive ability). as self-assessments of their ability to perform tasks inherent in this exercise by asking students to complete identical pre- and postcourse questionnaires.1 I scored all the data blind to whether the responses came from the precourse or postcourse assessment. The knowledge-based questions were eight short answer questions such as “Who typically writes an amicus curiae brief?,” “Who is a petitioner?,” and “In a legal case, what is the ‘holding’?” The mean number correct (of eight questions) on the precourse assessment was 2.09 (SD = 1.58); the mean number correct on the postcourse assessment was 5.45 (SD = 1.69), t(11) = 5.25, p < .01. The self-assessment questions asked students to gauge their ability to (a) organize a large amount of research-based data, (b) form and support an opinion on the basis of research-based data, and (c) speak in public for 30 min while being interrupted with questions. Students answered these questions on a 10-point Likert-type scale with response options ranging from 1 (no ability) to 10 (extensive ability). The data appear in Table 2. On all three items, students rated their ability as significantly higher after the exercise than before the exercise: organize research material, t(11) = 3.63, p < .01; form and support opinion, t(11) = 3.74, p < .01; speak in public, t(11) = 5.07, p < .01. Although it is difficult to determine to what extent the advocacy exercise, rather than the course itself, contributed to these results, the data generally show enhancements in both knowledge and skills. Creating and refining this activity has caused me to think hard about engaging students in novel, active learning paradigms that contrast radically with the typically passive way in which students learn in many classroom environments. It has also required careful 1 The data I report came from 12 students who comprised the most recent course. 212 attention to the notion of scaffolding. Over the course of the semester, I introduce students to successive aspects of this assignment and assign increasingly difficult readings, oral presentations of research studies, and more integrative writing tasks that culminate in the preparation and presentation of the advocacy exercise. This advocacy exercise requires students to locate, synthesize, and condense a large amount of empirical data into a concise, organized, and forceful written analysis and to present that analysis in an adversarial context, thinking “on their feet” and modifying their presentation as the situation demands. The assignment forces students to refine skills they developed in their research methods course and pushes some outside of their comfort zones. (Note that the mean precourse score on the item “Ability to speak in public for 30 min” was only 5.55.) Students treat this assignment very seriously. They meet with me outside of class to request help in structuring their arguments and preparing their briefs, they seek help from other instructional personnel on campus to improve their writing and speaking skills, and they present themselves in a very formal way when they are “in court.” This high level of professionalism, as well as data pointing to enhanced conceptual learning and improvements in abilities to organize complex empirical material and present arguments based on that material, suggests that the exercise is effective. References Harris v. Forklift Systems, Inc., 510 U.S. 17 (1993). Lockhart v. McCree, 476 U.S. 162 (1986). Maryland v. Craig, 497 U.S. 836 (1990). Mazzoni, G., & Memon, A. (2003). Imagination can create false autobiographical memories. Psychological Science, 14, 186–188. Teaching of Psychology Note Send correspondence to Edie Greene, Department of Psychology, University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, P.O. Box 7150, Colorado Springs, CO 80933; e-mail: egreene@uccs.edu. Both sample case descriptions and grading rubric are available from the author. Downloaded By: [University of Colorado] At: 23:30 14 January 2009 Roesch, R., Golding, S. L., Hans, V. P., & Reppucci, N.D. (1991). Social science and the courts: The role of amicus curiae briefs. Law and Human Behavior, 15, 1–11. Sell v. U.S., 539 U.S. 166 (2003). Williams, L. M. (1994). Recall of childhood trauma: A prospective study of women’s memories of child sexual abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 1167–1176. Vol. 35, No. 3, 2008 213