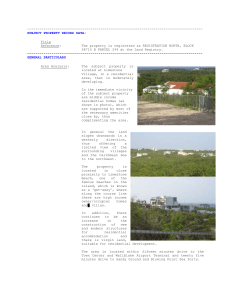

Where and How Much: Density Scenarios for the Residential Build-out...

advertisement