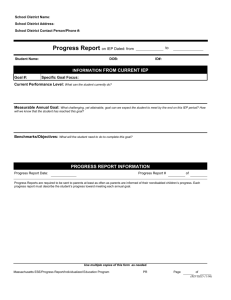

An Overview of Special Education and the IEP Process

advertisement