late-Night Comedy in Election 2000: Its Influence on Candidate Trait Ratings

advertisement

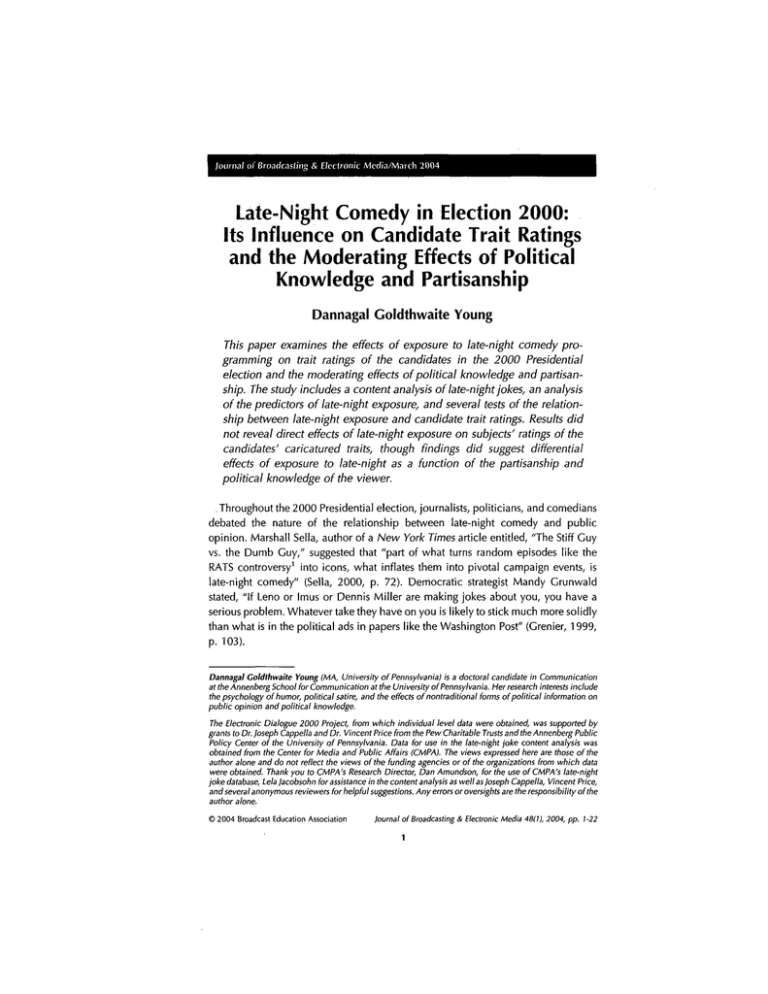

late-Night Comedy in Election 2000: Its Influence on Candidate Trait Ratings and the Moderating Effects of Political Knowledge and Partisanship Dannagal Goldthwaite Young This paper examines the effects of exposure to late-night comedy programming on trait ratings of the candidates in the 2000 Presidential election and the moderating effects of political knowledge and partisanship. The study includes a content analysis of late-night jokes, an analysis of the predictors of late-night exposure, and several tests of the relationship between late-night exposure and candidate trait ratings. Results did not reveal direct effects of late-night exposure on subjects' ratings of the candidates' caricatured traits, though findings did suggest differential effects of exposure to late-night as a function of the partisanship and political knowledge of the viewer. Throughout the 2000 Presidential election, journalists, politicians, and comedians debated the nature of the relationship between late-night comedy and public opinion. Marshall Sella, author of a New York Times article entitled, "The Stiff Guy vs. the Dumb Guy," suggested that "part of what turns random episodes like the RATS controversy' into icons, what inflates them into pivotal campaign events, is late-night comedy" (Sella, 2000, p. 72). Democratic strategist Mandy Grunwald stated, "If Len0 or lmus or Dennis Miller are making jokes about you, you have a serious problem. Whatever take they have on you i s likely to stick much more solidly than what is in the political ads in papers like the Washington Post" (Grenier, 1999, p. 103). Dannagal Goldfhwaite Young (MA, University of Pennsylvania) is a doctoral candidate in Communication at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. Her research interests include the psychology of humor, political satire, and the effects of nontraditional forms of political information on public opinion and political knowledge. The Electronic Dialogue 2000 Project, from which individual level data were obtained, was supported by grants to Dr. Joseph Cappella and Dr. Vincent Price from the Pew Charitable Trusts and the Annenberg Public Policy Center of fhe University of Pennsylvania. Data for use in the late-night joke content analysis was obtained from the Center for Media and Public Affairs (CMPA). The views expressed here are those of the author alone and do not reflect the views of the funding agencies or of the organizations from which data were obtained. Thank you to CMPA's Research Director, Dan Amundson, for the use of CMPA's late-night joke database, Lela Jacobsohn for assistance in the content analysis as well as joseph Cappella, Vincent Price, and several anonymous reviewers for helpful suggesfions. Any errors or oversights are the responsibility of the author alone. 0 2004 Broadcast Education Association lournal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 48(1), 2004, pp. 1-22 1 2 Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic MedidMarch 2004 Meanwhile, political comedians argued that since jokes are based on what the public already believes, their influence on public opinion was inconsequential. While speaking to AI Gore’s class at the Columbia Journalism School, David Letterman, host of CBS’s The Late Show, downplayed his role in the election, stating, “I would guess that very few votes were cast based on a joke that either I or Jay Len0 made’’ (Berner, 2001, p. 3). Jon Stewart, host of Comedy Central’s The Daily Show, argued that it was unlikely that people were influenced by such content since “[writers and comedians] need [viewers] to know something before they even make a joke about it” (Bettag, 2000). Similarly, Jay Leno, host of NBC‘s The Tonight Show, stated, “we (writers and comedians) reinforce what people already believe” (Shaap, 2000, p. 75). In spite of this debate’s high profile in the popular press, its presence in the academic literature i s far less prominent. This analysis i s an attempt to assess the effects of exposure to late-night programming on perceptions of the candidates in the 2000 campaign. The paper includes a content analysis of late-night jokes and a brief examination of the late-night audience. It also includes an analysis of the relationship between late-night exposure and ratings of the candidates on their caricatured traits. Here I explore the moderating roles of political knowledge and partisanship, assessing whether the effects of exposure varied with the knowledge or partisanship of the viewer. Political Humor, Persuasion, and learning Early studies assessing the persuasiveness of satire, such as editorial cartoons, hinted at satire‘s capacity to affect opinion, but with inconsistent results (Annis, 1939; Brinkman, 1968; Cruner, 1971). After the 1992 election, during which Clinton explored such nontraditional outlets as MTV, talk shows, and late-night programs, scholars became increasingly interested in the impact of such ”new news,” particularly on learning (Chaffee, Zhao, & Leshner, 1994; Davis and Owen, 1998; Hollander, 1995; McLeod et al., 1996). While some of this literature suggested audiences may learn about candidates’ positions through exposure to such programming (Chaffee et al., 1994; McLeod et al., 1996), other studies suggested that exposure might enhance viewers‘ perceived knowledge without increasing their actual knowledge (Hollander, 1995). Pfau, Cho, and Chong (2001) extended this research beyond learning as an outcome of exposure, to attitude change as an outcome, assessing the impact of exposure and attention paid to late-night as a source of campaign information on evaluations of candidates and views of the democratic process. Their results indicate a significant positive relationship between late-night exposure and perceptions of Gore and a nonsignificant negative relationship in the case of Bush. The authors speculate that jokes portraying Gore as wooden may have led viewers to see him as more human. But as Pfau et al. admit, ”The [reason why television entertainment talk Young/LATE-NIGHT COMEDY 3 shows mainly worked to Gore's advantage] probably lies in the content of Letterman's and Leno's jokes and thus lies outside the purview of this investigation" (Pfau et al., p. 97). The first goal of the following analysis, then, i s to explore the content of the jokes made by Len0 and Letterman throughout the 2000 campaign. RQ1: Which aspects of Gore and Bush's personalities were caricatured most by Len0 and Letterman in the 2000 election? The Late-Night Audience Two recent studies by the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press (2000, 2002) have helped scholars better understand trends in late-night viewing and the makeup of the late-night audience. Their most recent study (Pew Research Center, 2002) assessed predictors of late-night exposure by asking respondents how often they watched late-night television shows such as Letterman and Leno. The results indicated large differences by age group with 47% of respondents age 18-29 reporting watching regularly or sometimes compared to 34% of 30-44 year olds, 28% of 45-64 year old, and only 23% of respondents over age 65. A report published by Pew during the 2000 campaign (Pew Research Center, 2000) indicated that the number of people who reported learning about the campaign from late-night programs had increased slightly from 1996 to 2000. These increases were most notable among young people and those low in political knowledge. According to the study, America's youngest eligible voters (age 18-29), who reported the lowest use of newspapers and network news, reported receiving more campaign information from late-night than any other age group. And almost half of respondents low in knowledge reported learning about the campaign regularly from late-night, compared to only 20% of the high knowledge group. (Pew Research Center, 2000). As these statistics are based on self-reported learning, rather than on a correlation of exposure with actual knowledge gains, they should be considered measures of perceived rather than actual learning. Nonetheless, the Pew studies suggest that late-night i s watched more by young people and that the young and politically uninformed consider late-night to be a valuable source of political information. To extend Pew's findings and better understand what variables ought to be held constant when testing for late-night effects, the second question explores the demographic and sociopolitical characteristics of the late-night audience. RQ2: Who is in the late-night audience? The Psychology of Humor and its Cognitive Implications Late-night jokes are unlike traditional forms of political information as they require active audience participation. The incongruity theory of humor posits that since jokes introduce two incompatible "frames of reference" which the listener must 4 Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic MedidMarch 2004 reconcile by applying the appropriate cognitive rule, listener participation is necessary to construct a joke's meaning (Suls, 1972). To see a joke, Koestler (1 964) writes, "a listener has to work out by himself what is implied in the laconic hint; he has to make an imaginative effort to solve the riddle" (Koestler, p. 84), a process he refers to as interpolation. The fact that audience participation is required by this process points to important implications beyond the mere understanding of the joke. Several scholars have described the process of joke appreciation in terms of cognitive elaboration (Schmidt, 1994,2001; Wyer & Collins, 1992). Schmidt's experimental studies (1 994, 2001) indicate that memory for sentences and cartoons i s enhanced by the presence of humor, a finding he attributes to the process of "sustained attention and subsequent elaborative processes" (Schmidt, 2001, p. 31 1) that occurs in the face of humorous stimuli. According to network models of knowledge and memory (Higgins, 1989; Higgins, Bargh, & Lombardi, 1985), when information i s brought from long-term into working memory it is said to be "activated." Once activated, constructs are temporarily excited, and through frequent activation become more accessible and more likely to be used in later judgments (Bargh, Lombardi, & Higgins, 1988; Price & Tewksbury, 1997). Applying these concepts to the humor reconciliation process, it would seem that the activation of information to understand a joke is likely to increase the subsequent accessibility of that piece of information. Duai process models of attitude formation and change, such as the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) (Petty & Cacioppo, 1981, 1986) suggest that information processing can be conceptualized as taking a less effortful, peripheral route, or a more cognitively taxing, central route. According to ELM, the act of centrally processing a message and elaborating the information presented, increases the likelihood of recall and long-term attitude change. As the incongruity mechanism in humor mandates a form of cognitive elaboration on the part of the receiver to bridge the gap and see the joke, it would seem that recall and even attitude change should be enhanced as a result. In addition to these cognitive processes, the repetitiveness of late-night jokes renders their potential influence quite consequential. As explained by The Daily Show's John Stewart, audiences need to "know something before [comedians can] even make a joke about it" (Bettag, 2000). As a result, the candidate portraits received through late-night jokes highlight just a handful of traits with which viewers are already familiar. In a content analysis of political jokes made by late-night hosts from 1996 through 2000, Niven, Lichter, and Amundson (2003) found that most jokes are directed at the executive branch of government and that "the major late-night shows exhibit quite similar patterns in choice of targets, the partisan ratio of targets, and the subject matter of jokes" (Niven et al., p. 130). The study also found that jokes were predominantly aimed at the personal failings of politicians rather than public policy. Given the processes involved in understanding humor, it would follow that high exposure to such repetitive, simplified representations of the candidates would enhance accessibility, recall, and even persuasion in the direction Voung/LATE-NIGHT COMEDY 5 of these simplistic representations. Hence, exposure to late-night ought to move viewers' perceptions of the candidates in the direction of the gist of late-night candidate jokes. It is important to note that this study i s not a crucial test of the psychological mechanism underlying this process, but rather is designed to examine outcomes consistent with these theoretical mechanisms. HI: Individuals with greater exposure to late-night comedy programs will rate the candidates more consistently with their caricatured traits over time than individuals with less exposure to late-night programs, controllingfor demographics (age, gender, race, and education), political variables (partisanship and political knowledge), and media use (national news, local news, and newspaper). Political Knowledge and Partisanship As discussed earlier, research suggests that politically uninformed individuals report receiving more information through late-night comedy than individuals with higher levels of knowledge (Pew Research Center, 2000). Political knowledge has a notable history as an individual-level variable with the capacity to moderate communication effects (Delli Carpini & Keeter, 1996; McGuire, 1968, 1972; Zaller, 1992). Speaking in terms of general intelligence, McGuire posited that intelligent individuals are more likely to receive a message, but less likely to yield to it. Similarly, Zaller argued that the "politically aware," defined as those individuals who "pay attention to politics and understand what [they] have encountered" (p. 21), are more likely to be exposed to political messages but are also more likely to exercise resistance to their persuasive content. Delli Carpini and Keeter suggested that better-informed citizens have a greater capacity to evaluate political messages, either to retain the information if it is important or ignore it if it is not. If late-night viewers are less politically knowledgeable than traditional news viewers, then those viewing late-night programs may be receiving political information without the knowledge store to exercise such resistance, and hence may show stronger effects of exposure. H2: The relationship between late-night exposure and candidate trait ratings is stronger among those low in political knowledge than among those high in political knowledge. Political knowledge has been conceptualized and measured several different ways by political communication scholars (see Price, 1999). In an attempt to capture the presence and availability of general political information in long-term memory, Delli Carpini and Keeter (1 996) and Zaller (1 992) tested individuals' civics knowledge and knowledge of national political parties and leaders. In contrast, hoping to capture knowledge gains throughout the course of a campaign, Patterson and McClure (1 976) measured political campaign information by testing knowledge of presidential candidates' stands on various political issues. In general, these different measures are highly correlated (Price, 1999) but they do capture distinct knowledge constructs, with one's understanding of civics knowledge likely stored in long-term memory, 6 Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic MedidMarch 2004 and one‘s knowledge of presidential candidates increasing throughout a campaign, hence representing newly acquired information. An additional research question addressed by these analyses concerns how different types of political knowledge might vary in the extent to which they moderate late-night effects. RQ3: Do the moderating effects of a) political knowledge measures designed to capture the availability of general political knowledge in long-term memory differ from b) political knowledge measures that include constructs that have likely been acquired more recently? Research in the area of priming and agenda setting suggests that partisanship mitigates media effects (lyengar & Kinder, 1987; McLeod, Becker, & Byrnes, 1974, a phenomenon which might be explained by the enhanced accessibility of partisan attitudes that accompanies strong partisanship, leading to outcomes like selective perception and stronger attitude-behavior relationships (Fazio & Williams, 1986). Partisanship has been found to play several mediating roles in the context of the Elaboration Likelihood Model. One such role is to foster biasedprocessing (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). In this capacity, strong partisans with accessible attitudes and extensive attitude-relevant knowledge may be better versed in their own belief systems, and hence more likely to generate favorable cognitive responses to messages consistent with their opinion, and unfavorable responses to messages that contradict that opinion. This phenomenon might explain past findings in humor research indicating that people find jokes disparaging their own reference group less humorous than jokes disparaging others’ reference groups (La Fave, Haddad & Maesen, 1976; Priest, 1966; Weise, 1996). I would argue that the attitude-specific knowledge and enhanced attitude accessibility accompanying strong partisanship foster biased processing of political jokes, resulting in strong Democrats rating Bush (R) more consistently with late-night content than Republicans, and strong Republicans rating Gore (D) more consistently with late-night content than Democrats as late-night exposure increases. H3: Strong Democrats will rate Bush (R) more consistently with late-night content than Republicans; and strong Republicans will rate Gore (D) more consistently with late-night content than Democrats as late-night exposure increases. Late-Night Joke Content Analysis Methods To determine which aspects of Gore and Bush’s personalities were caricatured most in late-night content, a content analysis of late-night candidate jokes was completed using the late-night data base maintained by the Center for Media and Public Affairs, a nonprofit organization that tracks media coverage of politics and social issues. The sample includes texts of all Len0 and Letterman jokes about Bush and Gore made from January 1 through November 30, 2000. YounglLATE-NIGHT COMEDY 7 Coding scheme. The coding scheme consisted of a Bush variable and a Gore variable, each with 13 mutually exclusive categories, including 12 caricature categories and one "other" category' (see Appendix A). Categories were based on a preliminary qualitative analysis of late-night jokes by the author. Each joke was allowed one code per candidate. If a joke mentioned more than one trait of a particular candidate, only the first trait mentioned received a code, hence forcing mutual exclusivity on the categories. While some episodes were rerun, each joke was coded only once. The reliability of the coding scheme was tested between the author and a trained graduate student coder. Before coding, the author trained the graduate student in the details of the coding scheme, after which the author and student coder independently coded a random sample of 35 jokes, obtaining a Cohen's kappa of .74 for Gore caricatures and .67 for Bush caricatures. After a second meeting to clarify areas of systematic disagreement, they each independently coded a second random sample of 35 jokes, obtaining a Cohen's kappa of .81 for the Bush caricatures and .93 for the Gore caricatures. When a joke mentioned only one candidate, the other candidate variable was assigned a zero. Zeros were excluded before running reliability estimates. Consistent with Niven et al.'s (2003) observations, the results of the content analysis (see Table 1 ) indicate that most late-night jokes focused on the personal failings of the candidates, and were quite consistent across both programs. Jokes about Gore as stiff and dull were the most frequent Gore jokes made by both hosts, contributing 20% of the Gore jokes made by Len0 and 17% of the Gore jokes made by Letterman. Jokes painting Bush as unintelligent were the most common in both programs, contributing 24% of the Bush jokes made by Len0 and 34% of the Bush jokes made by Letterman. Overall, Letterman made half as many candidate jokes as Leno. There were 521 jokes made about Bush, 177 by Letterman, 344 by Leno; and 383 jokes made about Gore, I21 by Letterman and 262 by Leno. In addition to the boring-Gore and stupid-Bush caricatures, Gore's honesty and Bush's stand on the death penalty both received attention from late-night hosts. Jokes about Gore's tendency to exaggerate (14% of all Gore jokes), reinvent himself (7%) and engage in illegal fundraising practices (7%) all centered on questions of Gore's honesty. Meanwhile 17% of all Bush jokes raised the issue of his stand on the death penalty. It seems that while Niven et al. (2003) are correct in their observation that late-night jokes focus more on personality than public policy, their contention that "late-night humor i s determinedly non-issue oriented" (p. 130) is slightly complicated by the finding that Bush's death penalty position received considerable attention in 2000. In contrast, however, it is interesting to note that policy rarely emerged in Gore jokes, with only 2% of Gore jokes mentioning his stand on the environment. 8 Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic MedidMarch 2004 Table 1 Results of late-Night Joke Content Analysis Bush Total Percent Gore Total Percent IntelIigence Death penalty Drugs Alcohol Other Swearing Foreign affairs Malapropisms Failing campaign Silver spoon Smirk Friend of the rich Florida 142 82 60 48 47 35 27 22 12 10 4 3 2 28.74 16.60 12.15 9.72 9.50 7.09 5.47 4.45 2.43 2.02 .81 .61 .40 Stiff/boring/robotic Exaggerator Other DNC kiss Failing campaign Reinvents himself Illegal fundraising Makeup Florida Aggressivdrude Lieberman Environment Silver spoon 71 49 45 40 29 25 24 23 21 13 8 7 4 19.78 13.65 12.53 11.10 8.08 6.96 6.69 6.40 5.85 3.62 2.22 1.95 1.11 TOTAL 494 100.00 359 100.00 TOTAL Note. For descriptions of caricature categories see Appendix A. Again, the candidate personality traits most frequently caricatured in late-night content were Bush’s intelligence, Gore’s stiff appearance and dull personality, and Gore’s tendency to exaggerate or lie5. The dependent variables in the final section of the manuscript were selected to correspond with each candidate’s most caricatured trait(s). Hence, these analyses assume that knowledgeability reflects Bush’s intelligence, inspiringness reflects Gore’s stiff appearance and dull personality, and honesty captures Gore‘s image as an exaggerator or liar. Though one might argue that these traits are not identical to the caricatures portrayed in the jokes, the data limits the investigation to these variables. The Predictors and Effects of Late-Night Exposure Methods Survey data from the Electronic Dialogue 2000 project, designed to assess the role of electronic discussion during the 2000 presidential election, was used to assess the predictors of late-night exposure (RQ2) and to test the three causal hypotheses (Hl, H2, and H3). In February 2000, a random sample of American citizens 18 and older ( N = 3967) was selected from a nationally representative sample of respondents maintained by Knowledge Networks, Inc., of Menlo Park, California. The sample included households that had agreed to accept free WebTV equipment and service in exchange for YoungAATE-NIGHT COMEDY 9 completing surveys online. Participants were invited either to discuss politics online and complete monthly surveys (discussants), complete monthly surveys but not discuss politics online (control), or complete the baseline and final surveys only (set aside). Comparisons were made to be certain that late-night exposure was not confounded with experimental manipulations or group-level characteristics. Measures Late-night comedy exposure was obtained on the September survey (in the field from August 25-September 4,2000) from 64% of the discussants (N = 580) and 63% of the control group (N = 88) due to panel attrition over the course of the project. Respondents were asked, "Do you happen to watch any of the following entertainment programs on television?" followed by a list of programs including Jay Len0 and David Letterman. The options were: "NO" (Coded as 0), "Yes, but not very often" and "Yes, much of the time" (Coded as 2). Late-night exposure i s the (Coded as l), sum of Leno and Letterman viewing. While literature indicates that a combined index of exposure and attention is a superior measure of reception compared to exposure alone (Chaffee & Schleuder, 1986; McLeod & McDonald, 19851, this analysis is limited to the measures available, and hence only self-reported exposure i s used. Almost half of the sample (48%) reported not watching either program, and about one-third reported watching either program, but not very often. Less than one in ten respondents reported watching Leno or Letterman much of the time. Full political knowledgewas measured by combining three knowledge scales and was calculated as the percent correct for respondentswith valid responses on at least 12 of the 24 items. Correct answers were coded one and incorrect answers were coded zero. (For a complete list of items, see Appendix B.) The first battery consisted of seven questions regarding the candidates' backgrounds (four Democrat, three Republican). The second consisted of seven questions about the candidates' issue positions (four Democrat, three Republican) similar to Patterson and McClure's (1976) measure of candidate issue knowledge. The third battery consisted of 10 civics knowledge questions, similar to Delli Carpini and Keeter's (1996) and Zaller's (1992) political knowledge scales. The three batteries were combined into one full knowledge battery, with values ranging from 0-1, and with a Cronbach's a of 32. Civics knowledge was measured with 10 civics knowledge items (same as the civics knowledge component of the full political knowledge measure described above). The measure was calculated as the proportion correct for subjects with at least 5 out of 10 valid responses and a Cronbach's a of 31. For item details, see civics knowledge under Appendix B. Partisanship was obtained on the baseline survey in February. The scale ranges from 1 to 7 where 1 is strong Republican, 7 i s strong Democrat, and 4 independent. Evaluations of candidate traits were obtained from closed-ended questions. The July measure was obtained on a survey in the field from June 24 through July 19, and 10 Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic MedidMarch 2004 the October measure from October 7 through October 18. Respondents were asked how well various traits described the candidates. The traits-inspiring, knowledgeable, and honest-were issued in randomized order. Options were: Extremely well (3), quite well (2), not too well (I), and not well at all (0). These analyses use Bush‘s knowledgeable rating and Gore’s inspiring and honesty ratings to correspond with their late-night caricatures. Changes in trait ratings from July to October were calculated by subtracting the ]uly rating from the October rating. Of those subjects with valid late-night exposure measures, 41 6 also had valid July to October change scores. Analytical Procedure To determine who is in the late-night audience and hence what variables ought to be controlled when testing for late-night’s potential influence (RQ2), a regression model was run using predictors obtained on the February baseline survey to predict late-night exposure. Predictors included: age, gender (male = 1, female = O), race (white = 1, other = O), years of education, student (student = 1, non-student = O), partisanship (1 = strong Republican, 7 = strong Democrat), political efficacy3, cynicism4, follow politics (1 = never, 5 = almost all the time), full political knowledge (discussed above), and days in the past week respondent watched national news, local news, cable news, read the newspaper, and listened to political talk radio. Results are illustrated in Table 2. The relationship between late-night exposure and trait ratings (H1) was estimated using simultaneous OLS regression with listwise deletion. The dependent variables were changes in trait ratings from July to October. If a direct effect of late-night exposure were taking place, exposure would be a significant predictor in the models. For instance, if exposure to late-night were associated with decreases in Gore’s inspiring rating from July to October, a significant negative coefficient of late-night exposure should be found. The control variables included in the models were based on previous literature and on the results of RQ2. They include age, gender, race, education, partisanship, political knowledge, national and local news exposure, and newspaper reading. The results of the models testing H1 are illustrated in Model 1 in Tables 3 (Bush knowledgeable), 4 (Gore honest), and 5 (Gore inspiring). To assess the extent to which late-night’s influence on trait ratings was contingent upon the Partisanship of the viewer, the product of partisanship and late-night exposure was added to the models. Interaction terms assess nonlinear relationships in which the effects of one predictor variable on the dependent variable depend upon the level of some third predictor. For instance, if the effects of late-night on trait ratings depend upon a viewer’s partisanship, the product term (late-night * partisanship) will be significant. To reduce problems posed by multicolinearity (when two predictors in a model are so highly correlated that they inflate standard errors and mask significant relationships) product terms were centered by subtracting their means (Kleinbaum, Kupper, Muller, & Nizam, 1998). Young/LATE-NIGHT COMEDY 11 Once an interaction term is added to a model, the main effects (representedby the coefficient of either variable involved), illustrate each variable's effect on the dependent variable when the other is zero. Hence, the coefficient of late-night in a model that includes late-night * partisanship represents the effect of late-night on change in trait rating when partisanship is zero. As partisanship ranges from one to seven, this main effect i s not interpretable. To interpret the statistically significant interaction terms, predictor variables were set at their means and various levels of late-night and partisanship were substituted into the equations. Doing so produces predicted trait rating change scores for subjects with different combinations of partisanship and late-night exposure. The results of H3 are illustrated in Model 2 in Tables 3, 4, and 5. The extent to which late-night's effects were contingent upon the full political knowledge of the subject was tested by adding a product term (late-night * full political knowledge) to the original model (Model 3 in the tables). If H2 were correct, the interaction of full political knowledge and late-night would be significant such that the relationship between late-night and trait ratings would be stronger and more consistent with the caricatured depiction among individuals lower in knowledge. To explore how different forms of political knowledge interact with late-night in affecting trait ratings (RQ3), a fourth set of models added the product of late-night * civics knowledge. If H2 were correct, the interaction of civics knowledge and late-night would be significant such that the relationship between late-night and change in trait ratings would be stronger and more consistent with the caricatured depiction among those lower in civics knowledge. If civics knowledge (designed to capture availability of political information in long-term memory) provides a stronger defense against the influence of late-night than knowledge of candidate issue stands, biographies, and civics knowledge (which includes more recently acquired information), then the coefficient of civics knowledge * late-night will be stronger than the coefficient of full political knowledge * late-night. ResuIts While the coefficients in Table 2 do not suggest that full political knowledge was a significant predictor of late-night exposure, they do corroborate the Pew finding (2000, 2002) that younger people are more likely to tune into late-night than older people. The relationship between political knowledge and late-night that emerged in Pew's 2000 study (which i s not found in these data) can likely be attributed to the fact that their dependent measure was not exposure, but perceived learning from late-night, arguably a different construct altogether. According to Table 2, other significant predictors of late-night exposure were local news exposure, newspaper reading, and to a lesser extent, national news exposure. While one might explain the positive correlation between local news and late-night as an audience carry-over effect between the 11:OO p.m. news and the 11:30 p.m. airing of Len0 and 12 Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic MedidMarch 2004 Table 2 OLS Regression Predicting late-Night Comedy Exposure ( N = 577) B SE B (Constant) Demographic variables 1.68 0.41 Age Gender Race Education Student Political variables Partisanship Efficacy Cynicism Follow politics Full political knowledge Media use variables National news exposure Local news exposure Cable news exposure Newspaper reading Political talk radio exposure -.01 .oo -.03 Predictor - .04 .09 .13 - .04 .03 .03 .20 - .02 .05 -.I6 .02 -.03 .05 , .04 .05 .01 .04 .02 .05 .18 .05 .30 .02 .02 .02 .02 .02 P -.20*** -.02 -.02 -.07 .01 -.04 .04 - .04 - .03 .01 .1 O# .12* .03 .lo* .05 Note. Adjusted R2 = .05. ***p< ,001, **p < .01, *p < .05, #p < .l. Letterman, it i s more difficult to explain the correlation between newspaper reading and late-night. Perhaps both items capture general media use. As illustrated in Tables 3, 4, and 5, in none of the regression models is late-night alone a significant predictor of change in trait ratings, suggesting that late-night did not directly affect perceptionsof Bush and Gore in terms of their caricatured traits. Turning to H2, it appears that the extent to which late-night was associated with changes in Gore's inspiring rating varied with the political knowledge level of the viewer (see Table 5). This finding emerged both when using the full political knowledge scale and the civics knowledge scale alone. Although the coefficient of the civics knowledge interaction is slightly larger than that of the full political knowledge interaction, in general, the two measures of knowledge perform quite similarly as moderators of this effect (RQ3). Figure 1 illustrates the interaction with the full knowledge battery, indicating that subjects with various levels of political knowledge and no late-night exposure were similar in their change from July to October in how inspiring they found Gore, increasing an average of about .I 7 on the 4 point scale. When late-night exposure was high, on the other hand, the low knowledge respondents' inspiring ratings of Gore did not experience that positive shift over time, but rather stayed the same, YoungLATE-NIGHT COMEDY 13 Table 3 0 1 s Regression Predicting Changes in Knowledge Ratings of Bush from July to October Model 1 p B (SE B) (Constant) Demographics Age .32 (.35) Race Education Political variables Partisanship Political knowledge” p B (SE 8) Model 3 p B (SE B) .26 (.35) .oo .oo (.OW Gender Model 2 .oo .oo .oo .oo -.01 -.01 .oo (.OB) -.12 -.05 (.W -.02 -.05 (.02) -.lo -.05 (.I2) -.02 -.04 (.02) - .05 -.05 -.14** (.02) .17 .04 -.04 -.13* (.02) .20 .05 (.08) -.05 Local news Newspaper Late-night .01 (.02) .03 -.04 -.01 (.02) .01 (.02) .oo .05 .oo (.04 lnteraction terms Late-night X Partisanship Late-night x Full knowledge Late-night X Civics knowledge Adjusted R2 N .01 (.02) -.14** .04 .02 -.03 -.01 (.02) .01 (.02) .oo .oo -.01 LOO) -.02 (.08) -.12 -.06 (.I 2) -.03 -.08 -.03 (.02) (.24) Media use National news p B (SE B) .37 (.35) LOO) -.01 Model 4a .03 -.04 .04 ,05 .oo .oo (.04) -.04 -.13* (.02) .36 .12* (.18) .oo .02 (.02 -.03 -.01 (.02) .01 .03 (.02) .oo .oo (.W - .04 .13* - - - - - (.02) - - .01 - - - - - - - - .oo 389 .01 389 .oo 389 -.08 -.03 (.I 6 ) .01 391 Note. ***p< ,001, **p< .01, *p < .05, #p < . l . lnteraction terms are centered by subtracting means. Model 4, political knowledge is civics knowledge. moving -.03from July to October. Meanwhile, the high knowledge, avid late-night viewers found Gore slightly more inspiring over time, increasing about .19 on the 4point scale. As the interpretation of the interaction with civics knowledge produces a graph almost identical to the interaction with full political knowledge, only the Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic MedidMarch 2004 14 Table 4 01s Regression Predicting Changes in Honesty Ratings of Gore from July to October Model 1 B (SE B) (Constant) .08 (.37) p Model 2 p B (SE B) Model 3 p B (SE B) Model 4" ( SEB) p .OO .03 .06 (.37) Demographics .03 .02 Age (.OO) Gender .04 .05 Race .02 .02 -.07 Education -.07 .06 (.08) .06 .04 .03 -.03 -.07 (.03) Political variables .I 7** Partisanship -.01 Political knowledge" Media use National news .06 .16** -.01 -.04 (.26) .04 .04 .I 7*** .06 (.02) .03 (.I% .01 .03 .O1 03.2) .02 .03 Local news .03 .O1 (.02) - .03 Newspaper -.03 -.04 -.01 (.02) -.06 Late-night -.07 - .07 -.05 (.04) Interaction terms Late-night x Partisanship Late-night X Full knowledge Late-night x Civics knowledge .06 - - - - .06 Adjusted R2 .01 .01 .01 .01 N 390 390 390 392 Note. ***p < .001, **p < .01, * p < .05, #p < . I . Interaction terms are centered by subtracting means. Model 4, political knowledge is civics knowledge. interaction with the full knowledge scale i s represented graphically. These findings are consistent with H2 as subjects low in knowledge (whether measured exclusively by civics knowledge, or as a combined index with biographical, issue, and civics knowledge) shifted in a direction more consistent with late-night content than did Young/LATE-NIGHT COMEDY 15 Table 5 0 1 s Regression Predicting Changes in Inspiring Ratings of Gore from July to October Model 1 p B(SEB) (Constant) Demographics Age Model 2 -.27 (.36) -.30 (.36) .oo -.06 .oo -.08 -.04 LOO) -.05 -.04 Loa) (.08) Race Education -.03 -.01 .02 (.02) .05 p B(SEB) Model 4" p B (SEE) -.38 (.36) -.08 (.OO) Gender p B (SE 6) Model 3 -.04 -.02 (.la .05 .02 (.02) .OO -.07 (.OO) -.05 -.04 (.08) -.03 -.01 -.07 - .04 -.01 .03 (.02) .06 .05 .06 (.02) .26 .17*** .I 7*** Political variables Partisanship Political knowledge" Media use National news Local news .16** .05 (.02) .24 .24 .06 (.24) .02 (.02) .08 -.02 -.01 (.02) Newspaper Late-night lnferaction ferms Late-night x Partisanship Late-night X Full knowledge Late-night x Civics knowledge Adjusted RZ N .oo .01 (.02) -.05 -.03 (.04) - - - - - - .02 390 .16** .05 (.02) .23 .05 (24) .02 (.02) .08 -.03 -.01 .01 (.02) -.05 -.04 (.04) -.05 -.02 (.02) - - .02 390 .08 (.la) .07 .07 .02 -.03 -.01 -.04 (.02) (.02) .oo .06 (24) .oo .01 (.02) -.05 -.06 (.04) - .oo - .05 - .44 (.22) .03 390 .lo* - .12* .03 392 Note. ***p< ,001, **p< .01, *p < .05, # p < .1. Interaction terms are centered by subtracting means. Model 4, political knowledge is civics knowledge. high knowledge viewers. It is important to note that this effect i s indeed small, and was not found with Bush's knowledgeability or Gore's honesty ratings. Hypothesis three posited that the effects of late-night exposure would be stronger among strong partisans of the opposite party of the candidate being judged. This 16 Journal of Broadcasting& Electronic MedidMarch 2004 Figure 1 Gore's inspiring rating: The interaction of full political knowledge and latenight exposure +Low knowledge -Medium knowledge - A -High knowledge None Moderate High Late-night Note. Late-night's effects on Gore's inspiring rating are contingent on the level of full political knowledge of the respondent. Consistent with H2, subjects high in knowledge do not vary much in their rating of Gore with increased late-night exposure. Low knowledge subjects, however, rate Gore as less inspiring as their level of late-night exposure increases. Results of the civics knowledge * late-night interaction shown in Model 4 of Table 5 also follow this pattern. hypothesis is complicated by these findings. The interaction of partisanship and late-night is only significant in the model predicting changes in Bush's knowledgeability rating (see Table 3). When the product term i s interpreted, the pattern that emerges does not support H3, but instead shows strong Democrats and strong Republicans with similar changes in their judgments of Bush at higher levels of exposure to late-night. Among those subjects who did not watch late-night, Democrats rated Bush less knowledgeable over time- and Republicans rated him more knowledgeable over time. But partisans who were high consumers of late-night appeared identical in the extent to which their ratings of Bush's knowledgeability changed from July to October. They shifted only slightly compared to their nonviewing cohorts, with a net change of -.04 (see Figure 2). Discussion In 2000, Len0 and Letterman defined Gore and Bush's caricatures along simple one-dimensional lines. Gore was the cardboard cut-out, programmable exaggerator who wanted credit for everything. Bush was the guy who partied a little too hard in college, the underachiever whose genius was less than stellar. While these themes were consistent across both programs and repeated regularly throughout the cam- YoungLATE-NIGHT COMEDY 17 Figure 2 Bush’s knowledgeable rating: The interaction of partisanship and late-night exposure -Q z 0.301 I Q) gs g Q) 0.20 e T: 0.00 x =: J E - + -Republicans - +, 0.10 z o 0 -s- L Moderates -0.10 m o -0.40 None Moderate High Late-night Note. Late-night’s effects on Bush‘s knowledgeability rating are contingent on partisanship. Democrats with high exposure to late-night are less critical of Bush’s knowledgeability over time than Democrats with no exposure to late-night. Republicans with high exposure to late-night do not experience the increases in Bush’s knowledgeability ratings over time illustrated by non-viewing Republicans. paign, any direct effects they might have exerted on public opinion are too small in magnitude to find in the data, if they exist at all. In spite of the elaborate mechanism proposed and the selection of dependent variables based on actual late-night content, these data do not provide evidence of a direct effect of late-night viewing on perceptions of political candidates. While it is possible that the impact of exposure to late-night on public opinion occurred prior to July, and hence i s not captured by the models, the low frequency of candidate jokes made in early 2000 suggests that such an explanation i s quite improbable. These findings do support the contention that viewers of different political affiliations and with different levels of political knowledge (whether measured as civics knowledge or as a combination of candidate issue, biography and civics knowledge) may experience distinct effects of late-night exposure. However, these trends do not translate across candidates or across personality traits being judged. Rather, the moderating roles of partisanship and political knowledge in the late-night effects process appear to be both candidate and attitude-specific, a finding which complicates the proposed psychological mechanism. Also, while political knowledge may hinder the influence of late-night exposure in 18 Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media/March 2004 certain contexts (judgments of Gore’s inspiringness) consistent with H1, partisanship does not appear to foster the biased processing that would result in party members judging the opposing party’s candidate more consistently with late-night caricatures. Instead, the trend that emerges is reminiscent of a mainstreaming effect (Gerbner, Gross, Morgan, & Signorielli, 1980), as heavy exposure erodes differences between Democrats and Republicans in their candidate evaluations. Perhaps this trend operates as a function of late-night exposure, or perhaps late-night i s confounded with general media use, and general media use is responsible for the relationship. Although no similar trend was found in the Gore models, future studies might benefit from measuring general media use as well as late-night exposure to separate out these effects. There are numerous limitations that complicate these analyses. The first is posed by panel attrition over the course of this highly political project, illustrated by the N of 389 and 390 in the models; likely leaving us with a sample higher in higher political interest and sophistication than the average subject. Second, the Electronic Dialogue study, in which individuals were completing political surveys and/or discussing politics throughout the campaign, renders these circumstances quite unique. Third, as discussed in the measurement section, the key measure intended to capture reception of late-night content only includes three levels of exposure and ignores the role of attention to political information in late-night. It is impossible to say what impact these factors may have had, but future studies ought to maximize external and construct validity in a way that was not done here. Future research ought to address the cognitive consequences of late-night exposure posited to occur through humor reconciliation, including enhanced recall, salience, and persuasion. As the moderating roles of partisanship and political knowledge may vary by candidate and by the kinds of judgments being made, a detailed psychological mechanism to account for these variations is essential. In addition, the use of experiments would enable the humorous texts to be crafted with a desired outcome in mind, thereby establishing a closer link between content and effect. While such studies lack in external validity, they are necessary to understand the psychological channels through which humor might shape opinion. Finally, given late-night‘s unique audience and the potential moderating effects of such constructs as political knowledge and partisanship, individual differences ought to play a prominent role in future studies of the effects of exposure to late-night comedy programming. How should political communication scholars assess the effects of late-night humor in the campaign environment when its impact is diffused through other sources, such as news magazines and morning programs (Jamieson & Waldman, 2003)? Niven et al. (2003) recently found that the tone of news stories parallels the tone of late-night jokes when tracked over time. But should scholars assume that news influences joke content or vice versa? One of the most important, albeit discouraging, lessons to be learned through this exercise i s how the complexity of the campaign environment complicates the analysis of late-night humor’s effects. Even Young/LATE-NICHT COMEDY 19 including exposure to late-night programming in a model with extensive control variables leaves one wondering, "What is left?" Once the effects of two sources of information are "untied," hasn't one lost the very synergy that might make them interesting? These are the questions that will haunt researchers in the realm of entertainment and politics, particularly since the question of whether art imitates life or life imitates art remains unanswered. Until it has been answered - and until the debate between journalists, politicians, and comedians over the impact of political humor has come to a close -scholars ought to pursue experimental studies to assess underlying psychological processes involved, as well as macro-level analyses to track late-night content, its coverage in traditional media, and simultaneous shifts in public opinion. Appendix A: Coding Scheme for late-night Jokes Bush Codes. 1) Malapropisms: Bush's speaking abilities, excludingjokes that refer to his verbal competence in matters of foreign affairs, which are included under "Foreign affairs." (Letterman 9/14/00: GeorgeW. Bush said he would've loved to be on the show, unfortunatelyhe was uniminavalable.) 2) Foreign affairs: Bush's lack of knowledge in foreign affairs, the location of foreign countries and names of leaders. (Letterman 1/03/00: Boris Yeltsin's top ten New Year's resolutions:Wear a Hello My Name Is tag if he meets Bush.) 3) Intelligence: includes jokes that do not fit into the categories above, but comment upon Bush's lack of knowledge, or implied stupidity. (Leno 2/01/00: After the polls closed, networks declared McCain a big winner in New Hampshire. I guess this is the biggest setback for George Bush since he took his SATs.) 4) Alcohol: Bush's drinking problem, including references to his "party guy" past, unless they refer specifically to drugs, in which case go in the "drug" category. 5) Drugs: Bush's drug history (stated or implied). Also includes jokes suggesting that Bush cannot remember his college years. 6) Smirk Bush's smirk. 7) Friendof the rich: Bush policy helping only the wealthy. 8) Silver spoon: Bush's comfortable upbringing and use of father's name to obtain power. 9) Failing campaign: Bush's likely defeat and failing campaign. 10) Death penaly. Bush's position on the death penalty. 11) Swearing Bush calling the New York Timer: Adam Clymer a "major league asshole." 12) Florida: Post November 7'h references to Bush assuming that he is president before the race has been called. 13) Oh fe?' Gore Codes: 1) Stiffiboring/robotic Gore's stiff, boring persona or stiff mannequin-likeappearance. (Leno 2/10/00: Computer hackers have been attackingWeb sites all week. -computer hackers actually shut down AI Gore for two hours.) 2) Reinvents himself: Gore's changing personality and willingness to do or say anything to get elected. (Letterman 3/09/00: And [Gorel changes with the wind. He's a clever politician, man. Did you see him when he did the debate at the Apollo theater in Harlem?He was really trying to kiss up to the crowd. He goes. . . (As Gore): "My homies will give their propers.") 3) Exaggerator: Includes Gore's "misstatements" during the debates, and the notion that he invented the Internet. 4) Makeup: Gore's makeup on stage at the DNC and the debates. 5) DNC Kiss: Tipper and Gore's kiss at the DNC and their inability to keep their hands off of each other. 6) Environmental fanatic Gore's position on global warming and reputation as a tree-hugger. 7) Rude debate etiquettdaggressive: Gore's aggressive behavior during the debates, or elsewhere (E.g., references to Gore trying to be alpha male). References to the differences in Gore's demeanor between debates falls under "Reinvents himself." 8) Silver spoon: Gore's comfortable upbringing and use of his father's name or influence to obtain power. 9) Failing campaign: Gore's likely defeat and failing campaign, exceptwhen the joke referencesFlorida. Jokesmade after Nov 7Lh,are included under "Florida." 10) Lieberman: Joe Lieberman as a strategic choice, or references to Lieberman's religion. 11) //legal Fundraising Gore's Buddhist monk incident and campaign contributions from overseas. 12) Florida: Gore's reluctance to "let go" of the election. 13)0the? Appendix B: Knowledge Batteries Political knowledge. Each question was followed by randomized options. (In the case of biographies and issue positions, AI Gore and Bill Bradley were the Democratic options, and George W. Bush and John Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic MedidMarch 2004 20 McCain were the Republican options.) "Full political knowledge" includes all 24 items and "civic knowledge'' includes only the 10 civics knowledge items. Candidate Biographies: 1) Thinking about the Democrats, to the best of your knowledgewho a) Was a professional basketball player (Bradley); b) Is the son of a former United States Senator (Core); c) Voted for tax cuts proposed by President Reagan in 1981 (Bradley); d) Served in the United States Senate (Both). 2) Thinking about the RepublicansUohn McCain and George W. Bush), to the best of your knowledge, who a) Is a state governor (Bush); b) Is a United States Senator (McCain); c) Was a prisoner of war in Vietnam (McCain). Candidate lssue Positions: 1 ) Thinking about Democrats, to the best of your knowledge, who a) Supports a universal health care program (Bradley); b) Favors increased government funding of political campaigns (Bradley); c) Favors giving patients the right to sue their HMO (Both); d) Favors tax-free savings accounts to help parents pay for college (Core). 2) Thinking about Republicans, to the best of your knowledge, who a) Supports giving tax credits or vouchers to people who send their children to private schools (Both); b) Has pledgedto cut federal income taxes by over $1 trillion in ten years (Bush); c) Supports a ban on soft money campaign contributions (McCain). Civics Knowledge: 1) Which one of the parties is more conservative than the other at the national level? [Democrats, Republicans, DK] 2) Which one of the parties has the most members in the House of Representatives in Washington?[Democrats, Republicans, DKI 3) Which one of the parties has the most members in the U.S. Senate?[Democrats, Republicans, DKI 4) Who has the final responsibilityto decide if a law is Constitutionalor not?[President, Congress, SupremeCourt, DK] 5 ) Which one of the following is the main duty of Congress?[Write legislation; Administer the President's policies; Watch over the governments of each state; DK] 6) Whose responsibilityis it to nominatejudges to the Federal Courts?[President, Congress, Supreme Court, DK] 7) How much of a majority is needed for the U.S. Senate and House to override a presidentialveto? [Bare majority (one more than half the votes), Two-thirds majority, Three-fourths majority, DK] 8) Do you happen to know what job or political office is currently held by AI Gore?[U.S. Senator, US. Vice President, Governor of Tennessee, DK] 9) What job or political office is currently held by Trent Lott? [US. Senator, US. Ambassador to the United Nations, Chieflustice of the US. Supreme Court, DK] 10) What job or political office is currently held by William Rehnquist?[U.S. Senator, US. Ambassador to the United Nations, Chief Justiceof the U.S. Supreme Court, DKI Notes ' The "RATS" controversy refers to a political ad made by the Bush campaign in which the word "RATS" flashed on the screen. Republicans argued it was part of the word "DEMOCRATS," while Democrats argued that the Bush campaign was engaging in subliminal advertising. * The thirteenth "other" category consisted of jokes that either a) tapped into something mentioned less than three times throughout the campaign, orb) mentioned the candidate in the text, but did not make fun of him. For example, "Last Sunday [Gore] was in Washington at a gay rights rally and spoke out in favor of gay rights. Yesterday, at the Atlanta YMCA, he unveiled his new crime plan, calling for more police. Gore said if elected president, his top priority would be to add a second cop to the village people." The scale averages three items regarding whether the respondent has any say in what the government does, whether public officials care what the respondent thinks, and whether politics i s too complicated for the respondent (1 -5 scale where 5 is high efficacy, Alpha = ,636). The scale averages 5 items about trust in government, what the candidates talk about, if candidates tell the truth, how the candidates usually vote, and how honest the candidates are with the electorate (each item is coded 0-1 where 1 is the cynical response, Alpha = .57). While Bush's stand on the death penalty received considerable attention from late-night hosts, these analyses are limited to perception of candidates' personality traits. References Annis, A. D.(1939). The relative effectiveness of cartoons and editorials as propaganda media. Psychological Bulletin, 36, 628. Bargh, J. A,, Lombardi, W. J., Higgins, E. T. (1988). Automaticity of chronically accessible Young/LATE-NIGHT COMEDY 21 constructs in person * situation effects on person perception: It's just a matter of time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55, 599-605. Berner, K. (2001, April 5). Dave standup guy in Columbia gig, N e w York Daily News. 3. Bettag, T. (Executive Producer). ABC News. (2000, 18 September). Nightline [Television broadcast]. New York: ABC News. Brinkman, D. (1968). Do editorial cartoons and editorials change opinions? Journalism Quarterly, 45, 724-726. Chaffee, S. H. & Schleuder, J. (1986). Measurement and effects of attention to media news. Human Communication Research, 13, 76-1 07. Chaffee, S. H., Zhao, X., & Leshner, C. (1994). Political knowledge and the campaign media of 1992. Communication Research, 27, 305-324. Davis, R. &Owen, D. (1998). New media andAmericanpolitics. New York: Oxford University Press. Delli Carpini, M. & Keeter, S. (1996). What Americans don't know about politics and why i t matters. New Haven: Yale University Press. Fazio, R. H. & Williams, C. J. (1986) Attitude accessibility as a moderator of the attitudeperception and attitude behavior relations: An investigation of the 1984 Presidential election. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 505-51 4. Cerbner, G., Gross, L., Morgan, M., & Signorielli, N. (1980). The "mainstreaming" of America: Violence profile no. 1 1. Journal of Communication, 30, 10-29. Grenier, C. (1999). Late-night Gurus." World and 1, 74, 103. Cruner, C. R. (1971). Ad hominem satire as persuader: An experiment. Journalism Quarterly, 48,128-131. Higgins, E. T. (1989). Knowledge accessibility and activation: Subjectivity and suffering from unconscious sources. In J . S. Uleman & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), Unintended thought (pp. 75-123). New York Cuilford. Higgins, E. T. Bargh, 1, & Lombardi, W. (1985). Nature of priming effects on categorization. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 17, 59-69. Hollander, B. A. (1995). The new news and the 1992 Presidential campaign: Perceived vs. actual political knowledge. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 72, 786-798. lyengar, S. & Kinder, D. R. (1987). News that matters. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Jamieson, K. H. & Waldman, P. (2003). The press effect; Politicians, journalists, and the stories that shape the political world. New York: Oxford University Press. Kleinbaum, D. C., Kupper, L. L., Muller, K. E., & Nizam, A. (1998). Appliedregression analysis and other multivariable methods. Pacific Grove, CA: Duxbury Press. Koestler, A. (1964). The act of creation. London: Hutchinson and Co. La Fave, L., Haddad, J., & Maesen, W. A. (1976). Superiority, enhanced self-esteem, and perceived incongruity humor theory. In A. J. Chapman and H. C. Foot (Eds.), Humor and laughter: Theory, research and applications (pp. 63-91). New York: Wiley and Sons. McCuire, W. J. (1968). Personality and susceptibility to social influence. In E. F. Borgatta and W. W. Lambert (Eds.), Handbook of personality theory and research (pp. 1 130-1187). Chicago: Rand McNally. McGuire, W. I. (1972). Attitude change: The information-processing paradigm. In C. G. McClintock (Ed.), Experimental social psychology (pp. 108-141). New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. McLeod, J. M. Becker, L. B., & Byrnes, J. E. (1974). Another look at the agenda-settingfunction of the press. Communication Research, 7, 131-165. McLeod, J. M., Cuo, Z., Daily, K., Steele, C. A,, Huang, H., Horowitz, E., & Chen, H. (1996). The impact of traditional and nontraditional media forms in the 1992 Presidential Election. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 73, 401 -41 6. McLeod, J. M. & McDonald, D. C. (1985). Beyond simple exposure: Media orientations and their impact on political processes. Communication Research, 72, 3-33. Niven, D. Lichter, S. R., Amundson, D. (2003). The political content of late night comedy. Press/Politics, 8,118-1 33. 22 Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic MedidMarch 2004 Patterson, T. E., & McClure, R. D. (1976). The unseeing eye: The myth of television power in national politics. New York C. P. Putnam’s Sons. Petty, R. E. & Cacioppo, J. T (1981). Attitudes and persuasion: Classic and contemporary approaches. Dubuque, IA: William C. Brown. Petty, R. E. & Cacioppo, 1. T. (1986). Communication and persuasion: Central and peripheral routes to attitude change. New York: SpringerNerlag. Pew Research Center For the People and The Press. (2000, February). Audiences fragmented and skeptical: The tough j o b of communicating with voters [On-line Report]. Retrieved from: http://www.people-press.orgljanOOrpt2. htm Pew Research Center For the People and The Press. (2002, June). Public’s news habits little changed since September 1 7. [On-line Report]. Retrieved from: http:Npeople-press.org/ reports/display.php3?ReportlD=156 Pfau, M., Cho, J. & Chong, K. (2001). Communication forms in U.S. Presidential campaigns: Influences on candidate perceptions and the democratic process. Presw‘Po/itics,Q 88-1 05. Price, V. (1999). Political information. In J. P. Robinson, P. R. Shaver, and L. S. Wrightsman (Eds.), Measures ofpolitical attitudes (pp. 591-639). San Diego: Academic Press. Price, V. & Tewksbury, D.(1997). News values and public opinion: A theoretical account of media priming and framing. In G. A. Barnett and F. J. Boster (Eds.), Progress in the communication sciences (pp. 173-212). New York: Ablex. Priest, R. F. (1966) Election jokes: The effects of reference group membership. Psychological Reports, 78, 600-602. Schmidt, S. R. (1994). Effects of humor on sentence memory. journal o f Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 20, 953-967. Schmidt, S. R. (2001). Memory for humorous cartoons. Memory and Cognition, 29, 305-31 1. Sella, M. (2000, September 24). The stiff guy vs. the dumb guy. The New York Times Magazine, pp. 72-90. Shaap, D. (2000, July). Why are we laughing at Bush and Gore. George, 5, 72-103. Suls, J. (1 972). A two-stage model for the appreciation of jokes and cartoons: An informationprocessing analysis. In J.H. Coldstein and P.E. McGhee (Eds.), Psychology of humor (pp. 81-1 00). New York: Academic Press. Weise, R. E. (1996). Partisan perceptions of political humor. Humor 9, 199-207. Wyer, R. S., and Collins 11, J. E. (1992). A theory of humor elicitation. Psychological Review 99, 663-688. Zaller, J. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. New York: Cambridge University Press.