This article was downloaded by: [Hoffman, Lindsay] On: 9 April 2010

advertisement

![This article was downloaded by: [Hoffman, Lindsay] On: 9 April 2010](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/010502255_1-4a13851dc545cdfed47506e605e32405-768x994.png)

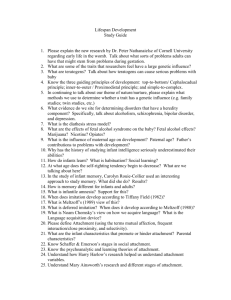

This article was downloaded by: [Hoffman, Lindsay] On: 9 April 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 921134652] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 3741 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Mass Communication and Society Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t775653676 Assessing Causality in the Relationship Between Community Attachment and Local News Media Use Lindsay H. Hoffman a;William P. Eveland Jr. b a Department of Communication, University of Delaware, b School of Communication, Ohio State University, Online publication date: 09 April 2010 To cite this Article Hoffman, Lindsay H. andEveland Jr., William P.(2010) 'Assessing Causality in the Relationship Between Community Attachment and Local News Media Use', Mass Communication and Society, 13: 2, 174 — 195 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/15205430903012144 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15205430903012144 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Mass Communication and Society, 13:174–195, 2010 Copyright # Mass Communication & Society Division of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication ISSN: 1520-5436 print=1532-7825 online DOI: 10.1080/15205430903012144 Assessing Causality in the Relationship Between Community Attachment and Local News Media Use Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 19:44 9 April 2010 Lindsay H. Hoffman Department of Communication University of Delaware William P. Eveland, Jr. School of Communication Ohio State University Numerous studies have demonstrated a relationship between community attachment and local news media use. Despite calls for panel studies to determine the direction of causality in this relationship, there is little evidence beyond cross-sectional surveys, which are often further limited to single communities. In order to contribute to the debate about causal direction, we conducted a four-wave national panel study with repeated measurement of community attachment and local news media use. Cross-sectional analyses confirmed the expected relationship between news use and community attachment. However, more conservative panel analyses controlling for a lagged measure of the dependent variable failed to produce evidence of causal relationships. The hypothesized role of population density and ethnic diversity Lindsay H. Hoffman (Ph.D., The Ohio State University, 2007) is Assistant Professor in the Department of Communication and Research Coordinator for the Center for Political Communication at the University of Delaware. Her research interests include politics and technology, media effects on political cognitions and behaviors, and perceptions of public opinion. William P. Eveland, Jr. (Ph.D., University of Wisconsin, 1997) is Professor and Graduate Program Director, Social and Behavioral Sciences, in the School of Communication at the Ohio State University. His research interests include how individuals cognitively process information and learn through communication behaviors. Correspondence should be addressed to Lindsay H. Hoffman, University of Delaware, Communication, 125 Academic Street, 250 Pearson Hall, Newark, DE 19716. E-mail: lindsayh@udel.edu 174 ATTACHMENT AND NEWS USE 175 Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 19:44 9 April 2010 as cross-level moderators of this relationship was examined using multilevel modeling. Methodological and theoretical reasons for the results are discussed and suggestions for alternative study designs are proposed. Interest in the relationship between communication—in its various forms— and community not only spans multiple disciplines, it dates back to early work on democracy by Greek philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle (see Friedrich, 1959; Wolin, 1960). Since the advent of the empirical study of mass communication, researchers have sought to understand the relationship between the local news media and community. The majority of current research on community and communication draws from the work of American sociologists such as Dewey (1927=1954), R. E. Park (1925; R. E. Park, Burgess, & McKenzie, 1952), and Janowitz (1952=1967; Kasarda & Janowitz, 1974). Unfortunately, almost all of the existing empirical work on this topic suffers from a number of limitations, most important and consistent of which is the absence of data capable of sorting out causal direction. That is, despite considerable evidence for a relationship, there is little evidence indicating whether community attachment produces increases in local news use or whether the use of local news produces higher levels of community attachment (Stamm, 1988). A second limitation is that most studies of news media use and community attachment are effectively case studies because they limit samples to a single community with a single media system. Thus, most individual studies cannot demonstrate consistency of relationships across community sizes and types of media systems. The purpose of the present study is to heed the calls of numerous scholars (e.g., Emig, 1995; Kang & Kwak, 2003; Stamm, 1988; Stamm, Emig, & Hesse, 1997; Stamm & Guest, 1991) by conducting a national panel study to assess the relationship between local news media use and community attachment. The data presented in this study allow us to (a) better verify the presence of a relationship between these concepts as well as, (b) better evaluate whether the relationship is causal, and if so, (c) determine whether the relationship is unidirectional or reciprocal and, if it is unidirectional, (d) confirm in which direction the influence flows. The data also permit us to determine whether the relationship between these variables is constant across communities or whether it varies, presumably due to the varying nature of local media systems and content across communities. DEFINING COMMUNITY ATTACHMENT AND RELATED CONCEPTS To begin, it is important to clarify what is meant by the various terms used by scholars conducting research in this area. For instance, researchers often Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 19:44 9 April 2010 176 HOFFMAN AND EVELAND, JR. refer to community integration, community ties, community attachment, community involvement, and various other concepts without clearly distinguishing among them. This confusion remains despite some solid work in the conceptualization and operationalization of these concepts. At least part of the problem is substantial disagreement about what best serves as a direct indicator of the integration=ties=attachment concept and what is either a cause or an effect of this concept (McLeod et al., 1996). It is first necessary to define community. Definitions of the concept vary by discipline, and some identify as primary characteristics the physical proximity (e.g., Anderson, Dardenne, & Killenberg, 1994), concern for common good (e.g., Ferrara, 1997), connection with neighbors and friends (e.g., Putnam, 2000), a sense of place (e.g., Jeffres, Atkin, & Neuendorf, 2002), or some combination of these physical and perceptual factors. In this study, we define community as individuals living in proximity with a shared sense of connection that arises from communication (see Jeffres, Atkin, & Neuendorf, 2002). Friedland and McLeod (1999) defined community integration as ‘‘that set of relations and processes that tie communities together and direct their change’’ (p. 203). This definition seems to make integration the superordinate concept among those to be discussed. That is, community integration refers very generally and broadly to everything that serves to advance ‘‘community’’ (which itself has historically had serious definitional problems; see Rothenbuhler, 2001). Rothenbuhler (2001) defined community ties as ‘‘bonds between the individual and community . . . [such as] people’s feelings of attachment to their communities, their involvement in local affairs, their identification with their community, and the patterns of behavior that keep people in the locality’’ (p. 163). This is a more restrictive definition but still includes both affect and behavior. It also operates specifically at the individual level. Of particular interest in this definition of community ties is the notion of individual community members’ ‘‘attachment to their communities.’’ Rothenbuhler, Mullen, DeLaurell, and Ryu (1996) defined community attachment as ‘‘identification with the community combined with an affective tie’’ (p. 447). Thus, community attachment is a subordinate concept to community ties broadly. Of interest, Stamm (1985) noted that the affective element of community ties has often been confounded with the cognitive one. What differentiates the affective link, according to Stamm, is that it refers to the psychological closeness to community, rather than the cognitive ‘‘identification with place’’ (p. 20). Therefore, community attachment as defined by Rothenbuhler combines the cognitive and affective elements of community ties as outlined by Stamm (1985). Community involvement, another term often used in the research literature, combines the cognitive and active interaction between self and Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 19:44 9 April 2010 ATTACHMENT AND NEWS USE 177 FIGURE 1 Conceptual clarification of the superordinate term community integration and its related terms. community (Rothenbuhler et al., 1996). Stamm (1985) further identified involvement as attending (awareness), orienting (thinking about community issues), agreeing (sharing concerns), connecting (talking and listening to others), and manipulating (working for change) in the community context (p. 23). Although these conceptualizations appear to be relatively straightforward, the terminology and measurement used across the empirical studies of these concepts is inconsistent, making summaries of the literature that take the conceptual intricacies into account difficult. To be explicit, the present study will focus on the concept of community attachment as defined by Rothenbuhler (2001; alternatively ‘‘cognitive’’ and ‘‘affective ties’’ according to Stamm, 1985), which includes both the cognitive identification with and affective feeling of closeness to one’s community (see Figure 1). UNDERSTANDING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN LOCAL NEWS USE AND COMMUNITY ATTACHMENT There are two dominant theoretical perspectives employed by researchers studying news media and community integration (Stamm, 1988). The first examines the contribution of local media to the formation of 178 HOFFMAN AND EVELAND, JR. individual–community relationships as attachment (media use ! community attachment). The second perspective is concerned with predicting media use from individual–community relationships (community attachment ! media use). We address both of these perspectives in turn. Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 19:44 9 April 2010 Local News Media Use Produces Community Attachment Janowitz (1952=1967) produced one of the most important works on community and local news media. He (see also Edelstein & Larsen, 1960; Suttles, 1972) was centrally interested in the role of small submetropolitan weekly newspapers in encouraging community attachment and involvement in large metropolitan areas. Janowitz claimed that these weeklies integrated the interests and views of the small interurban community, serving as a public forum that promotes consensus through an emphasis on common values rather than conflict. He saw these small weekly papers as performing a distinctly different function from the more conflict-ridden and commercial metropolitan newspaper. The community integration hypothesis—that local news media use can produce community integration—is most closely identified with the work of Janowitz. It predicts that community newspaper readership produces greater levels of integration by helping the individual orient to the community through the establishment and maintenance of local traditions. Local news, in this view, is said to emphasize values and interests on which there is a high level of consensus, interpreting relevant external events through the lens of the local community. Research in subsequent years has expanded Janowitz’s landmark study to incorporate not only small interurban weekly papers but also daily newspapers in small- to moderate-sized communities, and even local television news (e.g., Demers, 1996; Emig, 1995; Jeffres, Dobos, & Sweeney, 1987; McLeod et al., 1996; Rothenbuhler et al., 1996; Stamm et al., 1997; Viswanath, Finnegan, Rooney, & Potter, 1990). For instance, McLeod et al. found that use of local news media predicted higher levels of various types of community integration (including ‘‘psychological attachment,’’ a concept similar to Rothenbuhler’s community attachment). Similarly, Rothenbuhler and colleagues developed a set of structural equations predicting community attachment (and involvement) from news media use. They found that newspaper reading contributed significantly to community attachment, whereas television news use made no significant contribution. Jeffres, Atkin, and Neuendorf (2002) found that attention to newspapers was correlated with community attachment using a measure based on Rothenbuhler et al. but employed an expanded definition that included political efficacy. Each of these studies was predicated on the assumption of a causal direction running ATTACHMENT AND NEWS USE 179 from media use to feelings of community attachment, and each examined local media at the level of a metropolitan area rather than interurban papers. Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 19:44 9 April 2010 Community Attachment Produces Local News Media Use Although many communication scholars have taken the media-effects approach by assuming that local news media use causes community attachment, other researchers have taken what Stamm (1988) defined as the community attachment ! media use approach, also with generally supportive findings. This approach may be historically associated with the urban sociology work of Greer (1962, 1967), R. E. Park (1952; R. E. Park et al., 1925), and Merton (1950). Greer (1962) concluded that by virtue of belonging to community volunteer organizations, members are more likely to follow local news and actions of government, particularly if it affects the group. Westley and Severin (1964) examined length of residence and reported that people who had lived in the same community for 5 or more years were more likely to read a daily newspaper. However, as Stamm (1985) noted, their definition of readership did not specify a time frame for readership, making it easier to qualify as a reader. Rarick (1973) and Stone (1977) advanced the literature by looking at characteristics of households, rather than individuals, in explaining subscription to newspapers. Rarick concluded that length of residence and home ownership impacted likelihood of subscribing to a newspaper. Stone expanded on this idea and hypothesized that these household characteristics measured citizens’ stake in their communities. He concluded that residents committed to the local community were more likely to subscribe to the newspaper ‘‘as a matter of utility’’ (Stone, 1977, p. 514). Unfortunately, the conceptualization and measurement in these earlier studies do not map precisely onto the notion of community attachment that is the focus of the present study. Stamm and Weis (1986) predicted higher newspaper subscription among those active in both church groups and voluntary associations than among those active in only one of these groups—as well as those active in church groups and involved in church issues—than among those active but not involved. Both hypotheses were supported, and the authors concluded that ‘‘church group participation appears to be a significant step toward integration in the local community, which leads to a greater need to be informed about all kinds of local news’’ (p. 135). Each of these studies, then, finds support for the claim that community attachment leads to local news media use. 180 HOFFMAN AND EVELAND, JR. Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 19:44 9 April 2010 Limitations in Inferring Causal Effects Stamm et al. (1997) noted that there is abundant evidence of the correlation between news media use and community attachment (see, e.g., Jeffres et al., 2002), and this is consistent with our brief summary of the literature. Of interest, the correlational data employed in every one of the studies just described can support either model. The only way to categorize the research into support for one or the other models is the direction of causality assumed by the researchers. Stamm et al. (1997) argued that there is actually no reason to presuppose a direction of causality. They noted that ‘‘the fact the evidence can be read two different ways highlights the point we don’t really know what it is we know’’ (p. 98). This concern led them to call for something better than ‘‘the usual cross-sectional survey evidence, which confounds the two possible relationships between media use and community integration’’ (p. 98). This call reflects Stamm’s (1988) earlier lament that there has yet to be a single study that shows a temporal relationship in which newspaper use precedes community attachment. GOALS AND HYPOTHESES OF THE PRESENT STUDY We have chosen to examine the causal relationship between community attachment and local news media use. Greer (1967) emphasized that the legacy of Janowitz’s work lies in his advances in methodology (i.e., a content analysis with a sample survey). Since then, scholars have regularly used such methods but have not tested the relationship between community attachment and local news media use in a panel study. To build upon Janowitz’s and others’ work, we contribute to the literature by adding a more appropriate method—a panel study that has measures of both local news media use and community attachment in multiple waves of data collection. Thus, we answer the repeated calls for data better able to infer causal relationships among these concepts. Although previous research suggests that use of local news media is closely correlated with elements of community integration, such as community attachment, almost no evidence exists for the direction of causality or even whether or not the relationship is a causal one at all. Given the two primary perspectives on the relationship between community attachment and local media use we offer the following two predictions as the central hypotheses of our study: H1: There will be a significant positive effect of community attachment on local news media use such that prior community attachment will predict later news media use controlling for prior news media use. ATTACHMENT AND NEWS USE 181 Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 19:44 9 April 2010 H2: There will be a significant positive effect of local news media use on community attachment such that prior news media use will predict later community attachment controlling for prior community attachment. These two hypotheses are not necessarily competing; it may be that there are reciprocally causal effects that could be observed, in which case the data would be consistent with both hypotheses. A second benefit of the present study is that we are able to employ a representative national survey in our study as compared with the typical local community survey employed in nearly all prior research. There are a number of benefits of this broad sample, not the least of which is generalizability without concern for effects of research conducted in a single, relatively unique community. A more important benefit is that we can assess community-level variables as moderators of the presumed relationship between community attachment and local news use. Most prior research on the relationship between community attachment and local media use has been conducted within a single community. Thus, the nature of the community (and its media system) has been a constant within a given study but a variable across studies. To the extent that findings vary from study to study, unmeasured community-level variables—such as the nature of the media system, the level of conflict in the community, or the pluralism of the community more generally—may be able to account for those differences. For instance, some communities might have media systems that are more likely to encourage community attachment than others, and this could alter the relationship between community attachment and news media use across communities. In fact, Paek, Yoon, and Shah (2005) found that the structural context within which individuals live influences both news consumption and community participation. In the absence of direct information about the nature of local media systems such as ownership or content as a key product of ownership, two variables that might provide clues to the nature of the local media system are the population density of the community and ethnic diversity. As Tichenor, Donohue, and Olien (1980) argued, local newspapers in smaller, more homogeneous communities are likely to stress consensus over internal conflict. Local papers in larger, more pluralistic communities, on the other hand, are more likely to stress internal conflict over consensus. It stands to reason, then, that the positive effects of news media use on community attachment should be strongest in smaller, more homogeneous communities. It may even be that local news use could have a negative impact on community attachment in more pluralistic communities because of the nature of the content in these communities. Population density serves as one component of the community context as measured by Tichenor et al. (1980). Ethnic diversity, adapted from Hero and 182 HOFFMAN AND EVELAND, JR. Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 19:44 9 April 2010 Tolbert (1996) and Tolbert and Hero (2001), is an additional component that can contribute to social interaction, communication across groups, and integration into communities (Hindman, Littlefield, Preston, & Neumann, 1999). Although a more complete index of community structure would be ideal, we hypothesize that less dense and more ethnically homogeneous communities have local news media systems that focus more on consensus and less on conflict. With population density and ethnic diversity serving as a proxy for community pluralism, we hypothesize the following: H3: The relationship between local news media use and community attachment will be moderated by macrolevel variables of community population density and ethnic diversity, such that the strength of the positive relationship between local news media use and community attachment will decrease or be reversed as the density and diversity of the community increases. METHOD Sample This study employs a nationally representative panel survey with data collected in February 1999, June 2000, November 2000, and June 2001. The February 1999 data (T1) were collected as part of a commercial mail survey called the ‘‘Life Style Study,’’ which is conducted annually by Market Facts for the advertising agency DDB-Chicago. To produce a representative sample using quota sampling, the starting sample was drawn to reflect demographic distributions within the nine Census divisions of household income, population size, panel member’s age, and household size. This method was used to select approximately 5,000 respondents, from which 3,388 usable surveys were received. This represents a response rate of about 68%. Stratified quota sampling is a different approach from standard probability sampling procedures, but research suggests that the two methods produce comparable data (see Eveland & Shah, 2003; Putnam, 2000). For instance, based on his validation employing both longitudinal and cross-sectional comparisons of questions on both the Life Style studies and conventional probability samples, Putnam found ‘‘surprisingly few differences between the two approaches’’ with the mail panel approach producing data that is ‘‘consistent with other modes of measurement’’ (pp. 422–424). For the June 2000 wave of the study (T2) we developed a custom questionnaire and engaged Market Facts to recontact the individuals who completed the February 1999 Life Style Study. Due to some erosion in Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 19:44 9 April 2010 ATTACHMENT AND NEWS USE 183 the panel during the intervening 18 months, 2,737 questionnaires were mailed out. The response rate for this survey was 70.1%, with 1,902 respondents completing the questionnaire. Another custom questionnaire was developed for the November 2000 wave of the study (T3). This survey reassessed many of the relevant variables from T2. Once again, Market Facts recontacted individuals who completed the prior survey. Due to some erosion, 1,850 questionnaires were mailed to June=July 2000 respondents. The response rate for this survey was 71.1%, with 1,315 respondents completing the questionnaire. The final wave of data from this panel study was collected in June 2001 (T4; N ¼ 971). Again, many of the same measures that appeared in the surveys at T1, T2, and T3 were included in this questionnaire. It should be noted that at each wave there was some item nonresponse, and different analyses used variables as measured in different waves, so the sample size for each analysis is reported in the tables. The lowest sample size for any analysis is 934. This smallest sample size still gives us strong power to detect a small correlation of .10 at p < .05, two-tailed (power ¼ .92), as well as sufficient power to detect a small effect size (f2 ¼ .02) at p < .05 using the F test in a multiple regression context with 10 predictors, the highest number of predictors in our analyses (power ¼ .86).1 Measurement A number of demographic and structural variables were measured at T1 and included in the models as controls because past research suggested that they would be related to both local news media use and community attachment. Length of residence in the community (in years) was measured at T2 (M ¼ 23.2, SD ¼ 17.9). Each respondent was asked if he or she owned their residence, rented, or lived for free; this variable was dichotomized for analysis with 1 as owning and 0 as not owning (M ¼ .76, SD ¼ .42). Respondents were also asked if they were married (1; not married ¼ 0; M ¼ .66, SD ¼ .47) and whether they had children younger than age 18 living at home (1; not ¼ 0; M ¼ .43, SD ¼ .50). Gender was measured as a dichotomy with the high value (2) being assigned to women (M ¼ 1.61, SD ¼ .49). Age was measured as chronological age in years (M ¼ 48.25, SD ¼ 16.09). Education was measured as an ordinal variable from 1 (attended but not graduated from elementary school) to 7 (postgraduate education); the modal response was ‘‘attended college’’ (30.8%). Household income was also ordinal and ranged from 1 (under $10,000) to 15 ($100,000 or more). Median income was 1 Power analyses conducted using GPOWER (Version 2.0) by Faul and Erdfelder (1992). Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 19:44 9 April 2010 184 HOFFMAN AND EVELAND, JR. between $27,500 and $29,999; the most frequently reported was between $40,000 and $44,999. Population density was measured as the number of people per square mile in the metropolitan statistical area (MSA or PMSA or CMSA) in which the respondent resided. Data for this variable were obtained from the 2000 U.S. Census and were combined with our survey data based on codes assigned to each respondent at T1. Among those respondents for whom we were able to obtain a measure of community population size (N ¼ 2,714), the mean level of people per square mile of land area was 920.03 (SD ¼ 1437.90), although the range was from 12.50 (Casper, Wyoming MSA) to 13,043.60 (Jersey City, New Jersey PMSA). The calculation of ethnic diversity was adapted from Hero and Tolbert (1996), based on the original equation developed by Sullivan (1973). Also obtained from the 2000 U.S. Census, the percentage of ethnicities were computed with the following formula: diversity ¼ 1 – [(proportion Black)2 þ (proportion White)2 þ (proportion Asian)2].2 This proportion ranged from .05 (Altoona, Pennsylvania MSA) to .74 (Los Angeles–Long Beach, California PMSA) and averaged .33 (SD ¼ .16). Local news media use, which was measured at T2 (in the summer prior to the 2000 election) and T3 (immediately following the 2000 election), incorporated indicators of both local television news use and local newspaper use. Initially we had intended to measure newspaper and television news use as distinct forms of local news media use, but empirically, use of these two media loaded on the same factor and were highly correlated with one another. So to avoid multicollinearity problems in our regression models we constructed a single measure that included two indicators of local television news use and two indicators of local newspaper use. First, we asked about the number of days in the past week respondents had ‘‘watched stories about local government and politics on television’’ and ‘‘read articles about local government and politics in newspapers’’ on a scale from 0 (none) to 7 (every day). Then, we asked respondents to indicate their level of attention, on a scale from 1 (very little) to 10 (very close), to ‘‘stories about local government and politics on television’’ and ‘‘articles about local government and politics in newspapers.’’ We converted responses to each of the four items to Z scores so that all items were on the same metric. This index was reliable at both T2 (a ¼ .83; MT2 ¼ .0002, SD ¼ .82) and T3 (a ¼ .85; MT3 ¼ .0008, SD ¼ .83). 2 There was a category for ‘‘Hispanic,’’ but it was measured separately from race, so respondents could potentially answer both Hispanic and an additional race category. Therefore, this category was excluded from the computation. ATTACHMENT AND NEWS USE 185 Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 19:44 9 April 2010 Community attachment was measured at both T2 (June 2000) and T4 (June 2001) with two indicators designed to address community attachment: ‘‘I feel ‘at home’ in the community I live in’’ and ‘‘I would feel sad if I had to move away from this community’’ (wording adapted from Stamm, 1985, and Rothenbuhler et al., 1996). Respondents were asked to react to these items on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (definitely disagree) to 6 (definitely agree). These two items measured community attachment at both T2 (SpearmanBrown split-half reliability ¼ .67) and T4 (Spearman-Brown split-half reliability ¼ .63). Community attachment was high in both waves during which it was measured, ranging between the response options moderately agree and generally agree (MT2 ¼ 4.50, SD ¼ 1.23; MT4 ¼ 4.70, SD ¼ 1.17). RESULTS Table 1 presents the results of two initial multiple regression models that reflect the typical cross-sectional analysis approach in research on news media use and community attachment. These models examine the relationship between news media use and community attachment after the application of a variety of control variables believed to be related to both variables. The first model assumes that news media use is the dependent variable; the second model assumes community attachment is the dependent variable. TABLE 1 Cross-Sectional Models of the Relationship Between Community Attachment and News Media Use Length of residence Home ownership Having children at home Being married Education level Age Household income Community attachment (T2) News media use (T2) Adjusted R2 N News media use (T2) Community attachment (T2) .04 .01 .01 .00 .24 .24 .08 .12 — .151 1,839 .20 .06 .00 .02 .06 .09 .04 — .12 .106 1,839 Note. All coefficients are standardized betas. p < .05. p < .01. Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 19:44 9 April 2010 186 HOFFMAN AND EVELAND, JR. There are several significant predictors of local news media use in Table 1. Those who are more educated, are older, and have a higher income are more likely to use local news media. More important for the present purposes, however, community attachment also predicts local news media use after controls for the various demographic as well as structural variables. Using similar cross-sectional data and multiple regression analyses, other researchers have inferred similar support for the model in which community attachment encourages local news media use. The second model in Table 1, however, provides support for the community integration hypothesis of Janowitz (1952=1967) and others. First, it indicates that older respondents, those who have lived in the community for a relatively long time, and those with higher education are more attached to their community. It also implies that local news media use produces community attachment, even after controls for these other potentially important predictors. Although most scholars would acknowledge that one cannot infer causality from correlational data such as these, they might be inclined to at least argue that the data in our subsequent analyses, presented in Table 2, provide evidence of some relationship between these concepts, either unidirectionally causal or reciprocally causal. However, Table 2 leads us to a very different conclusion. In the analyses in this table we take advantage of our panel data by applying a control for the prior level of each dependent variable in predicting the current level of the dependent variable (i.e., a ‘‘conditional change model’’; see Finkel, TABLE 2 Panel Models of the Relationship Between Community Attachment and News Media Use Controlling Prior Levels of the Outcome Measure Length of residence Home ownership Having children at home Being married Education level Age Household income News media use (T2) Community attachment (T2) News media use (T3) Adjusted R2 N News media use (T3) Community attachment (T4) .03 .00 .00 .02 .00 .06 .08 .53 .04 — .334 1,265 .03 .05 .00 .02 .02 .10 .00 — .55 .03 .371 934 Note. All coefficients are standardized betas. p < .05. p < .01. Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 19:44 9 April 2010 ATTACHMENT AND NEWS USE 187 1995). These analyses indicate the relationship between the predictor variable and the outcome variable once the contribution of the prior level of the outcome variable has been removed. Some interpret these sorts of regression models as ‘‘change’’ models, which is accurate if one thinks of the change as change from what we would expect based on knowing the level of the dependent variable for a given individual at a prior point in time (Finkel, 1995). Thus, of the analyses presented in this article, it is those in Table 2 that best allow us to assess causality in the relationship between local news media use and community attachment. The first model in Table 2 reveals that news media use is quite stable over time. Local news use at T2 is a strong and significant predictor of local news use at T3 (b ¼ .53). However, after this prior level of local news use is accounted for, there is no relationship between community attachment at T2 and local news media use at T3. Indeed, the only variables that account for significant variance in local news use at T3 are local news use at T2 and household income. Interpreted another way, if we know what a person’s prior level of local news use is, knowing his or level of community attachment 6 months prior does not increase our accuracy of predicting the amount of local news use. Thus, in the conservative test, H1 was not supported. The second model in Table 2 indicates that community attachment at T2 is a very strong predictor of community attachment at T4—with a standardized regression coefficient of .55. This, in combination with the finding that only age significantly predicts T4 community attachment after controlling for T2 community attachment, suggests that community attachment is quite stable over even relatively long periods. Once this stability over time is taken into account, there appears to be no relationship between local news media use at T3 and community attachment at T4. Again, stated another way, local news use at T3 does not improve prediction of community attachment at T4 if we know the level of community attachment a year prior. Thus, using the most conservative test, H2 was not supported. More generally, the findings in Table 2 suggest that local news media use and community attachment are not causally related in either direction. One interpretation of these results is that prior cross-sectional research may have merely tapped into a spurious relationship between these two variables that covary and are very stable over time. H3 predicted that the effect of news media use on community attachment would be moderated by population density and ethnic diversity. To test this hypothesis, we employed multilevel modeling (using HLM version 6.02) to assess the impact of the macrolevel variable population density and diversity on the relationship between the microlevel variables news media use (T2) and community attachment (T2). As a preliminary step (see Park, Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 19:44 9 April 2010 188 HOFFMAN AND EVELAND, JR. Eveland, & Cudeck, 2008), we assessed the amount of variation in T2 community attachment that existed across communities of residence to determine if a significant portion of variance in the outcome measure was at the macrolevel. The intraclass correlation coefficient, which tests the proportion of variance across macrolevel units, was .015. That is, approximately 1.5% of variance in community attachment exists between communities. This is admittedly small, but as Hayes (2006) has asserted, there are often benefits to using multilevel modeling even when the intraclass correlation coefficient is near zero. We know before we conduct our test of H3 that there is very little variance in community attachment across communities. It is therefore likely to be very difficult to account for this variance by population density and diversity and the interaction of population density and diversity with local news media use. Nonetheless, we move forward with the remainder of the MLM analysis. We estimate the model to initially test the impact of T2 local news media use (Level 1 predictor) and population density and diversity (Level 2 predictors) on T2 community attachment. To maintain simplicity, we do not incorporate any additional control variables. The results indicate a significant relationship between local news media use and attachment (p < .001) as already indicated in Table 1. Population density was not a significant predictor of community attachment, but ethnic diversity was, suggesting that community attachment varies significantly as a function of ethnic diversity (gamma coefficient ¼ .82, SE ¼ .27, p < .01). This negative coefficient suggests that with greater ethnic diversity, community attachment decreases (conditional on population size being average, as these variables were grand-mean centered). In the final model,3 the effect of ethnic diversity on the relationship between local news media use and community attachment was not significant. Yet the effect of population density emerged as a significant moderator of the relationship between local news use and community attachment (gamma coefficient ¼ .000077, SE ¼ .000029, p < .01). As depicted in Figure 2, this is actually the reverse of our prediction because it suggests that population density positively affects the relationship between community attachment and local news use (conditional on ethnic diversity being average). Because we find no significant moderating role for ethnic diversity and population density produces an unexpected significant finding, H3 is not supported. 3 The model tested was: Level 1: Yij ¼ b0j þ b1j(local news useij) þ rij Level 2: b0j ¼ c00 þ c01(population sizej) þ c02(ethnic diversityj) þ u0j b1j ¼ c10 þ c11(population sizej) þ c12(ethnic diversityj) þ u1j Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 19:44 9 April 2010 ATTACHMENT AND NEWS USE 189 FIGURE 2 A model of community attachment as a function of local news use and population density based on final analytic results. Note. Population density was calculated from the average lower and upper quartiles. DISCUSSION The hypothesis that local news media use strengthens attachment to the community is not a new or innovative one, nor is the hypothesis that those who are strongly attached to a community are more likely to use local news media anything new. And it is not novel for a study to be able to demonstrate empirical data consistent with either of these hypotheses. The journals in communication for decades have been peppered with such studies; in fact, some of these studies form part of the core of mass communication research history. During this long history of research on the relationship between local news media use and community attachment (and its related concepts), scholars have repeatedly acknowledged the limitations of their cross-sectional survey data and implored future research to move beyond this limited data source to better understand the direction of the causal relationship—if any—between these two variables. One common recommendation is for researchers to conduct a panel study to help better assess causality. We followed this recommendation, employing measures gathered across four waves and nearly 2½ years, with a focus on the key measures gathered at Time 2, 3, and 4 between June 2000 and June 2001. Our results are likely to surprise those who believe that news media use causes community attachment and those who believe community attachment causes news media use. Employing our data as if it were Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 19:44 9 April 2010 190 HOFFMAN AND EVELAND, JR. cross-sectional, we were able to demonstrate the same sort of relationship found in decades of communication research. Because our analyses mimicking prior research (i.e., cross-sectional analyses in Table 1) produce findings consistent with that research, it is unlikely that the nature of our sample (national vs. most studies that employ local samples) or our particular measurement strategies were the reason for the null causal findings. But when we took full advantage of our panel data, as has been so often suggested by researchers limited to cross-sectional data, we found that there is no evidence of a causal relationship between community attachment and local news media use. The only thing that differs between the models supporting prior research and the models challenging prior research is the inclusion of control for prior levels of the outcome variable—exactly the step that allows us to best assess causal versus noncausal relationships in panel survey data such as these. We worked from the assumption that on a day-to-day basis local news media use reinforces attachment to community while at the same time attachment to community encourages local news media use. Thus, if some third variable intercedes to alter either community attachment or local news media use at a given point in time, we should see a subsequent change in the other variable at a future time point. The difficulty of this approach is twofold: First, it is hard to foresee events that would produce a change in either of these variables and to design a study to take advantage of such events. Second, events of that sort seldom affect all members of a national sample survey simultaneously. In other words, over time in a general population, there is strong stability in both local news media use and community attachment, as our data have shown. This, we believe, is a key reason for our null findings in Table 2. Once prior levels of a highly stable outcome measure are controlled, the shared variance between the predictor and outcome has essentially been completely removed. Put another way, it is relatively easy to predict either local news use or community attachment if we know the prior level of that variable as long as a year ago. If both variables are very stable over time, it will be difficult to observe any causal relationship between them, even with a well-done panel study, when prior measures are of the outcome are controlled. What methodological solutions are there to this dilemma? One option would be to plan a study around a society- or community-wide event that could change either news use or community attachment—essentially a natural experiment. One such event that could change local news use is a local election campaign. Our study was designed to detect such effects by taking place over the course of an election year, which—as it turns out—was a dramatic and contested election at the national level. Local news use was measured 6 months before and immediately after the 2000 election. Our measure Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 19:44 9 April 2010 ATTACHMENT AND NEWS USE 191 of community attachment was measured 6 months before the election and 6 months after, providing a full year for community attachment to change. However, apparently the 2000 election was not sufficient to seriously disrupt individual patterns of local news use, at least based on our finding of a strong relationship between measures of local news use over time. It is likely that finding a shared social-level event that would disrupt community attachment would be even more difficult. What other options are there? One of the more interesting approaches is that of Stamm and his colleagues (e.g., Stamm & Weis, 1986). They have tried to tap into the direction of this relationship by beginning with individuals who are assumed to not have lengthy or strong community attachment—that is, newcomers to the community. In our study, the average respondent had lived in his or her community (as opposed to a specific residence) for 20 or more years. This is not dissimilar to Kang and Kwak’s (2003) mean length of residence of about 22 years. In McLeod et al. (1996), however, the mean length of residence was measured at one’s current residence, and was a much shorter 2½ years. This suggests that question wording on as simple a measure as length of residence can have great influence on the outcomes of analyses. It also implies that, when measuring community attachment without defining the parameters of ‘‘community,’’ length of residence in community is perhaps a more appropriate measure than length of residence in one’s home. Further research should assess how often people move from home to home in a metro area without changing their local media uses. Ultimately, we conclude that length of residence in community, rather than current home, is a better gauge. Length of residence also provides some other insights into likelihood of expressing community attachment. Individuals who had lived in their communities for a long time have most likely already formed longstanding attachments to the community—if this were ever to happen. By contrast, many newcomers have no prior level of attachment to a community, and if they have moved from far enough away, they also have no history of local news media use in the given community. Stamm and Weis (1986) focused on the way that newcomers might use local media in their first months in a community and how this media use might facilitate later community attachment. They have also considered the different roles media could play for those at different stages in a settling cycle. Work in this vein is important and should continue with greater vigor than most scholars have devoted to it. A study combining long-term panel analyses, as we have conducted here, with special attention to how newcomers become integrated into a community has great promise in further specifying causal direction. A second central goal of the present study was to determine whether population density and ethnic diversity served as moderators of the effects of local Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 19:44 9 April 2010 192 HOFFMAN AND EVELAND, JR. news media use on community attachment. In lieu of media content data from the approximately 200 communities from which our sample is drawn, we employed the simplifying assumption that smaller and more ethnically homogeneous communities would have local news media systems that focused more on consensus and less on conflict, as found by Tichenor et al. (1980). We further assumed that media content focused on consensus would produce stronger attachment to the community. By contrast, we expected that larger, more dense, and more heterogeneous communities would be likely to have local media focused more on conflict, which would at best not encourage integration into the community, and at worst could actually deter it. However, our multilevel modeling analysis suggests little evidence in support of these expectations. In fact, our data suggest the opposite of at least one expectation. We found that in more densely populated communities, increased local news use is associated with increased feelings of community attachment. This finding could suggest that local news provides a common experience for people to share, particularly when they reside in densely populated areas. Perhaps local news foster a ‘‘common bond of local identity’’ (Kaniss, 1991, p. 3), thus cultivating stronger feelings of community attachment. However, we should note that community pluralism, in the traditional sense, is not defined purely by population density and=or ethnic diversity; it is also defined by other factors that we have not measured here (see Tichenor et al., 1980). Even though the original research was focused more on media content than effects, consistent measurement of community pluralism would strengthen future research. We suggest that the inclusion of the number of businesses and voluntary groups with which citizens can get involved, the diversity of local power structures, as well as direct measures of media content within each community as other measures of community structure. However, the results reported here provide initial support for the idea that even simple proxies do result in significant effects on community attachment, and deserve attention in future research on the topic. Despite the ultimate lack of support for our three hypotheses, our study does have a number of advantages over prior research. The panel design of our study—often called for by researchers in this area—allowed us to demonstrate the strong stability in the central concepts in this study. We were able to use this design to demonstrate that not only are cross-sectional studies on very unstable ground making causal inferences in this domain of research, but that evidence of causality may be even more elusive than previously thought. The other advantage of our study is that it was not limited to a single community and thus not susceptible to criticism that a relationship between local news use and community attachment was the product of a unique media system and community. In the end, however, we must continue the call for more complex and innovative research designs. ATTACHMENT AND NEWS USE 193 Only panel studies that track individuals over time, beginning when they enter communities or when communities are significantly disrupted by outside events, are likely to be capable of sorting out the causal ambiguities inherent in this area of great theoretical interest. Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 19:44 9 April 2010 REFERENCES Anderson, R., Dardenne, R., & Killenberg, G. M. (1994). The conversation of journalism: Communication, community, and news. Westport, CT: Praeger. Demers, D. P. (1996). Does personal experience in a community increase or decrease newspaper reading? Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 73, 304–318. Dewey, J. (1954). The public and its problems. Denver, CO: Alan Swallow. (Original work published 1927) Edelstein, A. S., & Larsen, O. N. (1960). The weekly press’ contribution to a sense of urban community. Journalism Quarterly, 37, 489–498. Emig, A. G. (1995). Community ties and dependence on media for public affairs. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 72, 402–411. Eveland, W. P., Jr., & Shah, D. V. (2003). The impact of individual and interpersonal factors on perceived news media bias. Political Psychology, 24, 101–117. Faul, F., & Erdfelder, E. (1992). GPOWER: A priori, post-hoc, and compromise power analyses for MS-DOS [Computer program]. Bonn, Germany: Department of Psychology, Bonn University. Ferrara, A. (1997). The paradox of community. International Sociology, 12, 395–408. Finkel, S. E. (1995). Causal analysis with panel data (Sage University Paper series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, 07–105). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Friedland, L. A., & McLeod, J. M. (1999). Community integration and mass media: A reconsideration. In D. Demers & K. Viswanath (Eds.), Mass media, social control, and social change: A macrosocial perspective (pp. 197–226). Ames: Iowa State University Press. Friedrich, C. J. (1959). The concept of community in the history of political and legal philosophy. In C. J. Friedrich (Ed.), Community (pp. 3–24). New York: Liberal Arts Press. Greer, S. (1962). The emerging city: Myth and reality. New York: Free Press. Greer, S. (1967). Postscript: Communication and community. In M. Janowitz (Ed.), The Community press in an urban setting: The social elements of urbanism (pp. 245–270). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Hayes, A. F. (2006). A primer on multilevel modeling. Human Communication Research, 32, 385–410. Hero, R. E., & Tolbert, C. J. (1996). A racial=ethnic diversity interpretation of politics and policy in the states of the U.S. American Journal of Political Science, 40, 851–871. Hindman, D. B., Littlefield, R., Preston, A., & Neumann, D. (1999). Structural pluralism, ethnic pluralism, and community newspapers. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 76, 250–263. Janowitz, M. (1967). The community press in an urban setting: The social elements of urbanism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1952) Jeffres, L. W., Atkin, D., & Neuendorf, K. A. (2002). A model linking community activity and communication with political attitudes and involvement in neighborhoods. Political Communication, 19, 387–421. Jeffres, L. W., Dobos, J., & Sweeney, M. M. (1987). Communication and commitment to community. Communication Research, 14, 619–643. Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 19:44 9 April 2010 194 HOFFMAN AND EVELAND, JR. Kang, N., & Kwak, N. (2003). A multilevel approach to civic participation: Individual length of residence, neighborhood residential stability, and their interactive effects with media use. Communication Research, 30, 80–106. Kaniss, P. (1991). Making local news. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Kasarda, J. D., & Janowitz, M. (1974). Community attachment in mass society. American Sociological Review, 39, 328–339. McLeod, J., Daily, K., Guo, Z., Eveland, W., Bayer, J., Yang, S., et al. (1996). Community integration, local media use, and democratic processes. Communication Research, 23, 179–209. Merton, R. (1950). Patterns of influence: A study of interpersonal influence and of communications behavior in a local community. In P. F. Lazarsfeld & F. Stanton (Eds.), Communications research 1948–1949 (pp. 180–219). New York: Harper & Brothers. Paek, H., Yoon, S., & Shah, D. V. (2005). Local news, social integration, and community participation: Hierarchical linear modeling of contextual and cross-level effects. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 82, 587–606. Park, H. S., Eveland, W. P., Jr., & Cudeck, R. (2008). Multilevel modeling: Studying people in contexts. In A. F. Hayes, M. D. Slater, & L. B. Snyder (Eds.), The Sage sourcebook of advanced data analysis methods for communication research (pp. 219–245). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. Park, R. E. (1952). Human communities: The city and human ecology. Glencoe, IL: Free Press. Park, R. E., Burgess, E. W., & McKenzie, R. D. (1925). The city. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Touchstone. Rarick, G. (1973). Differences between daily newspaper subscribers and non-subscribers. Journalism Quarterly, 50, 265–270. Rothenbuhler, E. W. (2001). Revising communication research for working on community. In G. J. Shepherd & E. W. Rothenbuhler (Eds.), Communication and community (pp. 159–179). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Rothenbuhler, E. W., Mullen, L. J., DeLaurell, R., & Ryu, C. R. (1996). Communication, community attachment, and involvement. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 73, 445–466. Stamm, K. R. (1985). Newspaper use and community ties: Toward a dynamic theory. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. Stamm, K. R. (1988). Community ties and media use. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 5, 357–361. Stamm, K. R., Emig, A. G., & Hesse, M. B. (1997). The contribution of local media to community involvement. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 74, 97–107. Stamm, K. R., & Guest, A. M. (1991). Communication and community integration: An analysis of the communication behavior of newcomers. Journalism Quarterly, 68, 644–656. Stamm, K. R., & Weis, R. (1986). The newspaper and community integration: A study of ties to a local church community. Communication Research, 13, 125–137. Stone, G. (1977). Community commitment: A predictive theory of daily newspaper circulation. Journalism Quarterly, 54, 509–514. Sullivan, J. L. (1973). Political correlates of social, economic, and religious diversity in the American states. Journal of Politics, 35, 70–84. Suttles, G. (1972). The social construction of communities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Tichenor, P. J., Donohue, G. A., & Olien, C. N. (1980). Community conflict & the press. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. ATTACHMENT AND NEWS USE 195 Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 19:44 9 April 2010 Tolbert, C. J., & Hero, R. E. (2001). Dealing with diversity: Racial=ethnic context and social policy change. Political Research Quarterly, 54, 571–604. Viswanath, K., Finnegan, J. R., Jr., Rooney, B., & Potter, J. (1990). Community ties in a rural Midwest community and use of newspapers and cable television. Journalism Quarterly, 67, 899–911. Westley, B., & Severin, W. (1964). A profile of the daily newspaper non-reader. Journalism Quarterly, 41, 45–50, 156. Wolin, S. S. (1960). Politics and vision: Continuity and innovation in Western political thought. Boston: Little, Brown.