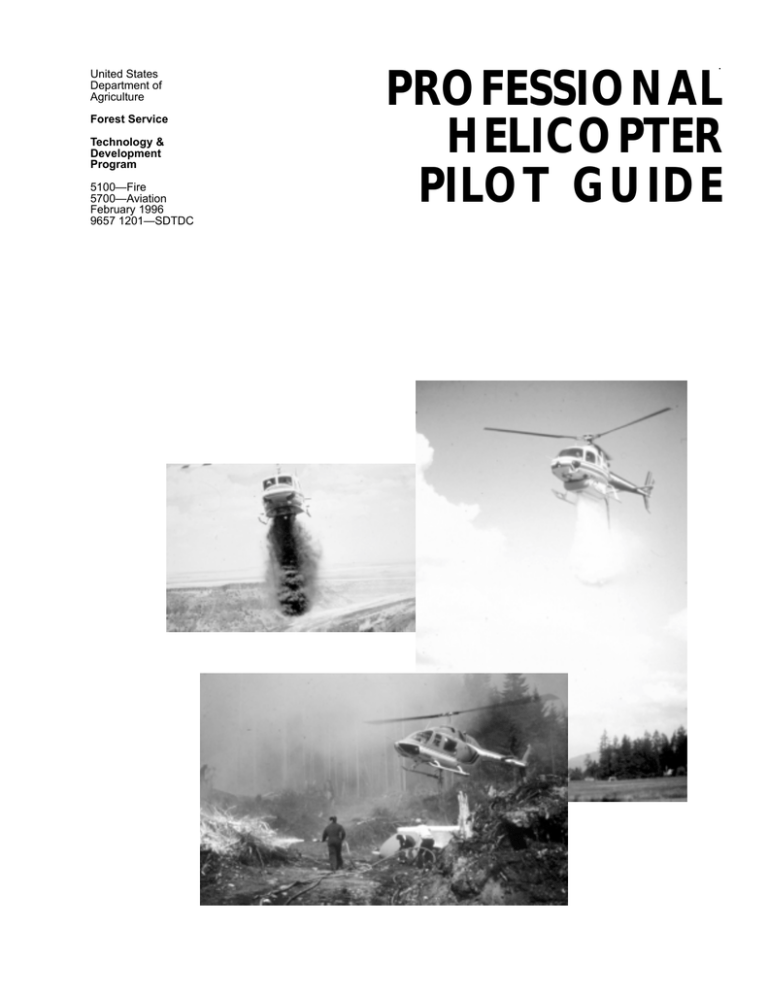

PROFESSIONAL HELICOPTER PILOT GUIDE United States

advertisement