A NEW GOAL FOR PUBLIC EDUCATION: SCHOOLS AT

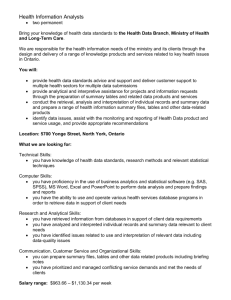

advertisement