Competition issues in the Tobacco Industry of Malawi

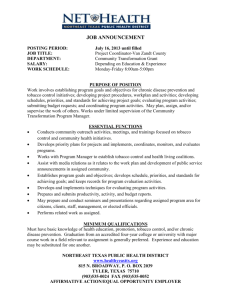

advertisement