T U A

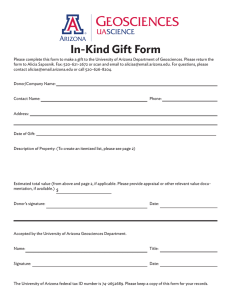

advertisement