Document 10466856

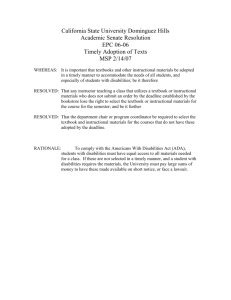

advertisement