Document 10465665

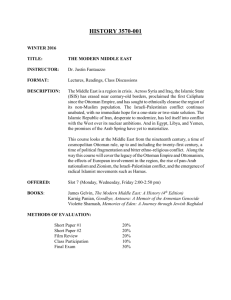

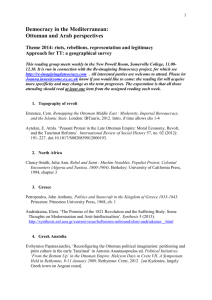

advertisement