Aftercare Strategy for Investors in the Occupied Palestinian Territory

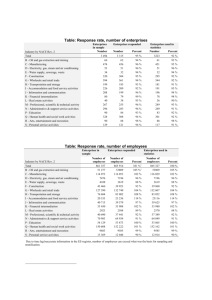

advertisement