TD United Nations Conference UNITED

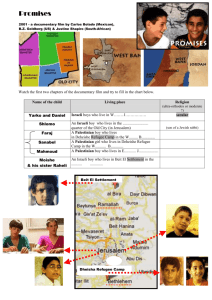

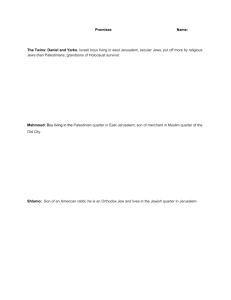

advertisement