Non-Tariff Measures and Regional Integration in the

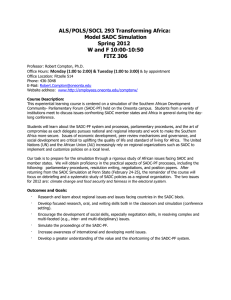

advertisement