Document 10455718

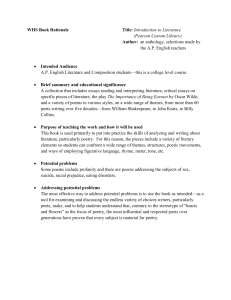

advertisement