Spring 2008

REACHOUT NEWS

School of Social Work

Stephen F. Austin

State University

Child Welfare Professional Development Project

Inside this issue:

Selecting and Working

with an Adoption

Therapist

Selecting and Working With an Adoption Therapist 1-6

Region V News

7

East Texas Heart Gallery

8

Child Welfare

Information Center

9

Earn One Hour Credit

1011

CWPDP Staff

12

REACHOUT NEWS

Published by

Child Welfare Professional

Development Project

School of Social Work

Stephen F. Austin

State University

P. O. Box 6165, SFA Station

Nacogdoches, Texas 75962

Tel: (936) 468-1846

Fax: (936) 468-7699

E-mail: bmayo@sfasu.edu

Funding is provided by contract with

the Texas Department of

Family and Protective Services.

All rights reserved. This newsletter

may not be reproduced in whole or in

part without written permission from

the publisher. The contents of this

publication are solely the

responsibility of the Child Welfare

Professional Development Project

and do not necessarily reflect the

views of the funders.

Reprinted with permission from Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2005). Selecting and Working With an

Adoption Therapist: A Factsheet for Families. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Adoption has a lifelong impact on those it touches, and members of adoptive families may want professional help as concerns arise. Timely intervention by a professional skilled in adoption issues often can prevent concerns from becom‐

ing more serious problems. Professionals with adoption knowledge and experience are best suited to help families identify connections between problems and adoption and to plan effec‐

tive treatment strategies. Sometimes a diffi‐

culty that a child is experiencing can be directly linked to adoption, but sometimes the connection is not readily apparent. In other situations, issues that seem on the surface to be related to adoption turn out not to be at all. It is important that the therapist understand that although the adoptive family is often not the source of the child’s problems, it will be within the context of the new family relationships that (Continued on page 2) From the Director…..Becky Price-Mayo, MSW, LBSW

April and May are very busy months for all of us with lots of ball games and end of the year school activities! We hope that you find the training opportunities offered through the SFA School of Social Work convenient for your hectic schedules. The feature article, “Selecting and Working with an Adoption Therapist,” is the last in a series on adoption. Recent articles discussed successful transition from fos‐

ter care to adoption, addressed specific adolescent adoption issues, and offered sugges‐

tions for helping children adjust to their adoptive family of a different race or ethnicity. Each of these articles provides information that is also very relative to foster parenting. Remember to complete the enclosed learning activities and evaluation and give to your caseworker for ONE HOUR TRAINING CREDIT! Since the last REACHOUT issue, the 11th annual Foster and Adoptive Training Confer‐

ence was attended by participants from over 19 counties in East Texas! Even though the conference was held early this year, there was a big crowd, and the conference was again very highly rated by those that completed evaluations. Special thanks to Judy Crone, Region V Foster Parent Council Representative, for stepping in midstream and serving as chair of the conference planning committee; and to CPS staff, foster parent associations, private placing agencies, child welfare boards, and social work students (Continued on page 12)

Page 2

REACHOUT NEWS

Selecting and Working With an Adoption Therapist continued . . . Professionals Who Provide Mental Health Services (Continued from page 1)

the child will begin to heal. This fact sheet offers information on the different types of therapy and providers available to help adoptive families, and it gives some suggestions on how to find an appropriate therapist. Professionals Who Provide Mental Health Services Many different types of professionals provide mental health services. The person or team best suited to work with a particular family will depend on the family’s specific issues, as well as the professional’s training, credentials and experience with adoptive families. Pediatrician or Family Practice Physician These medical doctors specialize in childhood or adolescent care and typi‐

cally treat routine medical conditions. They serve as primary care physicians who refer children for additional diag‐

nostic studies or procedures and who coordinate referrals to specialists. Psychiatrist These medical doctors (with M.D. de‐

grees) specialize in the diagnosis and treatment of medical and emotional dis‐

orders and substance abuse. After com‐

pleting medical school, psychiatrists receive postgradu‐

ate training in psychiatric disorders, various forms of psychotherapy, and the use of medicines and other treatments. Some psychiatrists complete further train‐

ing to specialize in such areas as child and adolescent psychiatry. Psychiatrists are able to prescribe medications. Clinical Psychologist A clinical psychologist has completed a doctoral degree (Ph.D. or Psy.D.) in psychology and usually has com‐

pleted advanced courses in general development, psy‐

chological testing and evaluation, as well as psycho‐

therapy techniques and counseling. Many clinical psy‐

chologists develop a subspecialty in child and adoles‐

cent development, psychological testing, or family therapy. Clinical psychologists assess and treat mental, behavioral and emotional disorders, including both short‐term crises and longer term mental illnesses. Clinical Neuropsychologist A clinical neuropsychologist holds a Ph.D. degree. These specialists have completed training in biological and medi‐

cal theories related to human behavior. Their postgraduate training focuses on the assessment and treatment of brain diseases and injuries, and neurological and medical condi‐

tions, including traumatic brain injury and learning and memory disorders. These professionals may be able to help in distinguishing organic (medical) problems from psycho‐

logical problems. Social Worker A social worker has completed a bachelor’s (B.S.W.) or master’s (M.S.W.) degree in social work. Social workers are trained to focus on a child or family within the child or family’s social en‐

vironment. Some social workers may refer to themselves as psychothera‐

pists; however, they may or may not have professional training in psycho‐

logical testing. Licensed clinical social workers (LCSWs) have a graduate degree and have passed a clinical test to become licensed in their state to offer counseling to individuals and families. Licensure and titles differ from state to state. Marriage and Family Therapist Marriage and family therapists have graduate degrees in counseling or psychology and may have taken a licensing exam to receive their marriage and family therapy (MFT) license. Almost all states have licensing laws for marriage and family therapists. These professionals evaluate and treat mental and emotional disorders and other health and behavioral problems, addressing a wide array of relation‐

ship issues within the context of the family system. Family therapists focus on communication‐building and on family structure and boundaries within the family. Licensed Counselor A licensed professional counselor has a graduate degree in a specialty such as education, psychology, pastoral counsel‐

ing, or marriage and family therapy, as well as a state li‐

cense to practice counseling. Licensed professional counsel‐

ors diagnose and provide individual or group counseling with a variety of techniques. (Continued on page 3)

Page 3

Selecting and Working With an Adoption Therapist continued . . . Approaches to Therapy (Continued from page 2)

Pastoral Counselor Pastoral counselors include pastors, rabbis, ministers, priests and others who provide faith‐based therapy and counseling. They usually have a graduate degree (many have completed doctoral training), and many also have a special certification in pastoral counseling. They focus on supportive interventions for individuals or families, using spirituality as an additional source of support for those in treatment. Not all individuals who provide faith‐based counseling have been formally trained or are credentialed as pastoral counselors. It is important for adoptive families to share openly with their mental health profes‐

sional that their family includes one or more adopted persons and to inquire about the counselor’s training and experience related to working with adoptive families and adopted persons. A growing number of states offer a postgradu‐

ate certificate to mental health pro‐

fessionals to help them understand the dynamics of adoption and to tailor treatment modalities to the needs of families and individuals impacted by adoption. Approaches to Therapy Different mental health professionals use different types of treatment. The type of treatment or the combination of treatments chosen may depend on the type and sever‐

ity of the presenting issue, the age and developmental level of the child, and even the experience and prefer‐

ences of the professional and family. Parents should be sure to ask prospective therapists about the different types of treatment that they might use. Some of these different types are described below. (A resource that rates the effectiveness of different treatment interven‐

tions for specific populations of children and families is the National Registry of Evidence‐Based Programs and Practices at http://modelprograms.samhsa.gov/

template_cf.cfm?page=effective_list.) Play Therapy Therapists customarily use this form of therapy with very young children who may not be able to express their feelings and fears verbally. The therapist will engage the child in games using dolls and other toys, since play is a way for children to communicate. Through gentle prob‐

ing, the therapist will try to draw the child out. In this way, the child may be able to act out feelings and reveal deep‐seated emotional trauma. Individual Psychotherapy This therapy may take many forms. Often the therapist will work to help the client first express problems verbally and then find ways to manage them. This type of therapy tends to stress that people should assume responsibility for their own actions and ultimately for their emotional well‐being. The therapist will offer challenges, interpreta‐

tions, support and feedback to the client. Group Therapy This therapy allows a small group of clients with similar problems to discuss them together in an organized way. Group therapy makes efficient use of a skilled therapist’s time and offers the extra advantage of feedback from peers. Occasionally, family members may be asked to join the group. Group therapy frequently is used with adolescents and usually is the treatment of choice for individuals and families affected by substance abuse. Family Therapy Increasingly popular, family therapy is based on the premise that all psychological problems reflect a dysfunc‐

tion in the “family system.” The term “dysfunction” means that members of a group or system are working together in a way that is harmful to some or all of its mem‐

bers. The therapist requests the active participation of as many family members as possible and focuses on gaining an understanding of the roles and relationships within the family. Family therapy seeks to achieve a balance between the needs of the individual and those of the larger family system. Behavior Modification A commonly used form of therapy, behavior modification has many practical applications. The basic approach in behavior modification is to use immediate rewards and punishments to replace unacceptable behavior with desir‐

(Continued on page 4)

Page 4

REACHOUT NEWS

Selecting and Working With an Adoption Therapist continued . . . Treatment Settings (Continued from page 3)

able behavior. The therapist will identify specific changes desired and will establish a system of rewards and punishments. The reasons behind the objectionable behavior are seen as irrelevant; the focus is on change. This therapy is especially useful with children who may not be inclined or able to examine and understand their inner feelings. Cognitive Therapy Cognitive therapy is based on the belief that the way we perceive situations influences how we feel emotion‐

ally. It is typically time‐limited, problem‐solving and focused on the present. Much of what the patient does is solve current problems through learning specific skills, in‐

cluding identifying distorted think‐

ing, modifying beliefs, relating to others in different ways and chang‐

ing behaviors. effectiveness. As a relatively newer form of therapy, few studies of attachment therapy have been evaluated for outcomes. Treatments such as “holding therapy,” “rebirthing ther‐

apy,” or other types of treatment that involve restraint of the child or unwelcome or disrespectful intrusion into the child’s physical space have raised serious concerns among parents and professionals. Some states have writ‐

ten statutes or policies that restrict or prohibit the use of these therapies with children in the care or custody of the public agency or adopted from it. Other therapies There are a number of other types of therapies, as well as variations of thera‐

pies, that may prove useful. These may include art therapy, music therapy and couples therapy. Parents should ask the professional to explain the treatment and goals before deciding on a particular therapy. Attachment Therapy Attachment therapy includes a number of different approaches to therapy with children, but all ap‐

proaches are based on common principles and theories of attach‐

ment and healthy development. Attachment therapy (sometimes incorrectly equated with holding therapy) includes an ever‐expanding continuum of interven‐

tions based on treatment theories from an array of therapeutic approaches, including behavioral and cog‐

nitive therapies. The focus of any attachment therapy should be to build a secure emotional attachment between the child and the parents. Because the primary focus is on the attach‐

ment relationship, not on the child’s symptoms, one or both parents must be active participants in the therapy. The basis of attachment therapy is that the develop‐

ment of a trusting attachment relationship will provide the security essential to healing the psychological, emo‐

tional and behavioral issues that may have developed as a result of earlier disruptions and trauma. These is‐

sues may include posttraumatic stress disorder, grief and loss, depression and anxiety. While some families find attachment therapy to be a useful approach, there is less evidence to support its Treatment Settings Therapy may take place as in‐home ther‐

apy, outpatient counseling, group or residential treatment, or inpatient hospi‐

talization. Most therapy sessions take place in an outpatient setting. This means that the client is seen in the therapist’s office, typically in a 50‐minute session once a week. Most emo‐

tional and psychiatric problems do not become serious enough to require treatment beyond this level. Many adoption‐sensitive therapists believe that therapy for adoptive families benefits from a more flexible time schedule and is best done when the entire family is in‐

cluded. Sometimes a child can best be treated with the limits and structured environment that a residential treatment cen‐

ter provides. Residential treatment is often the treatment of choice for children and teens with emotional, behav‐

ioral or substance abuse problems. Residential treatment centers, which provide 24‐hour care, are generally private, nonprofit facilities set up for children with severe psychiatric or substance abuse needs. They may be organized in individual community homes, in a campus‐type setting of cottages, or in a large (Continued on page 5)

Page 5

REACHOUT NEWS

Selecting and Working With an Adoption Therapist continued . . . Finding the Right Therapist (Continued from page 4)

institution (similar to a hospital setting). Residential treatment programs focus on the development of positive coping skills and personal responsibility. Behavioral ther‐

apy often is practiced in residential treatment programs; that is, the child’s good behavior will bring about appro‐

priate rewards and privileges. Children in residential treatment usually have regular visits with their parents. Family connections are critical to help motivate children to change their behavior so that they can return home. Hospitalization in a psychiatric hospital is available for clients with serious emotional problems that cannot be modified through outpatient therapy. It may be neces‐

sary for children who become suicidal or dangerous to themselves or others to be hospitalized to avert a crisis. It is important that parents stay involved; in fact, most child and adolescent units of psychiatric hospitals insist that parents participate in family meetings or therapy. If they are not automatically included, parents should be proactive in emphasizing the involvement of the family in their child’s treatment. Finding the Right Therapist Locating the right therapist requires that a parent iden‐

tify some prospective therapists who have adoption ex‐

perience and then conduct preliminary interviews to find the one who seems best able to help the child or family. Identifying Prospective Therapists It is important that parents take the time to find a mental health provider who has the experience and expertise required to address their needs effectively. Professionals with adoption knowledge and experience are best suited to help families identify connections between problems and adoption and to plan effective treatment strategies. At a minimum, a therapist must: tion agencies and adoptive parent support groups have lists of therapists who have been trained in adoption is‐

sues or who have effectively worked with children in foster care and adoption. Some adoption agencies and specialized post‐adoption service agencies have mental health therapists trained in adoption on staff. Parents can check with the following resources for thera‐

pist recommendations: •

•

•

•

•

•

•

be knowledgeable about adoption and the psycho‐

logical impact of adoption on children and families

•

be experienced in working with adopted children and their families

•

know the types of help available for adoption‐related issues and problems

•

and have received training in working with adoptive families.

Parents may contact community adoption support net‐

works, use the Internet, and ask their placement agency for referrals to therapists. Many public and private adop‐

state or local mental health associations

public and private adoption agencies

local adoptive parent support groups

specialized post‐adoption service agencies

state adoption offices

national and state professional organizations Interviewing Prospective Therapists Using the recommendations that they gather, parents can call prospective therapists or schedule an initial interview to find out basic information. Some therapists will offer an initial brief consultation that is free of charge. Parents should start by giving the clinician a brief description of the concern or problem for which they need help. The following are some questions to discuss: •

•

agency social workers involved in the child’s adoption

What is your experience with adoption and adoption issues? (Parents should be specific about the adoption issues that impact their prob‐

lem, such as open adoption, transracial adoption, search for birth relatives, children who have ex‐

perienced abuse or institutionalization, and chil‐

dren with attachment difficulties.) •

How long have you been in practice, and what degrees, licenses or certifications do you have? •

What continuing clinical training have you had on adoption issues? •

Do you include parents and other family mem‐

bers in the therapeutic process? •

Do you prefer to work with the entire family or only with the children? (Continued on page 6)

Page 6

REACHOUT NEWS

Selecting and Working With an Adoption Therapist continued . . . Working With a Therapist (Continued from page 5)

•

Do you give parents regular reports on their child’s progress? •

Can you estimate a time frame for the course of therapy? •

What approach to therapy do you use? (See “Approaches to Therapy,” page 3.) •

What changes in the daily life of the child and family might we expect to see as a result of the therapy? •

They should refrain from using therapy sessions as pun‐

ishment for a child’s misbehavior. Family members must communicate regularly with the therapist and ensure that the therapist has regular feedback about conditions at home. The success of therapy depends heavily on open and trusting communication. Parents may want to request an evaluation meeting with the therapist 6 to 8 weeks after treatment begins and regular updates thereafter. Evaluation meetings will help all parties evaluate the progress of treatment and offer the opportunity to discuss the following: •

Do you work with teachers, juvenile justice per‐

sonnel, daycare providers, and other adults in the child’s life, when appropriate? •

There are other practical considerations when choosing a therapist. Parents should be sure to ask about: •

progress on problems that first prompted the request for treatment •

the therapist’s tentative diagnosis (usually necessary for insurance reimbursement)

coverage when the therapist is not available, espe‐

cially in an emergency

•

appointment times and availability

•

fees and whether the therapist accepts specific insur‐

ance, adoption subsidy medical payments, or Medi‐

caid reimbursement payments (if applicable).

Working With a Therapist If the child is the identified client in therapy, the family’s involvement and support for the therapy is critical to a positive outcome for the child. An adoption‐competent therapist will value the participation of adoptive parents. Traditional family therapists not familiar with adoption issues may view the child’s problems as a manifestation of overall family dysfunction. They may not take into account the child’s earlier experiences in other care set‐

tings and may view adoptive parents more as a part of the problem than the solution. Adoption‐competent therapists know that the adoptive parents will be em‐

powered by including them in the therapeutic process and that no intervention should threaten the parent child relationship. Parents’ commitment to the therapy may also contribute to the success of the therapeutic process. For instance, parents are obligated to keep scheduled appointments. progress toward mutually agreed‐upon goals for treatment approaches and desired outcomes

•

satisfaction with the working relationship between the therapist and family members

•

the therapist’s evaluation of the chance that therapy can improve the situation that prompted treatment

Conclusion Members of adoptive families may encounter issues at different points in their lives that affect their behavior and emotional well‐being and that require treatment from a professional therapist. Adoption‐competent thera‐

pists, who understand adoption issues and adoptive fam‐

ily dynamics, are best suited to provide clinical interven‐

tions. With some research, parents can find the therapist best able to support their child and family. For contact information on state adoption offices and lo‐

cal adoptive parent support groups, access Child Welfare Information Gateway’s National Adoption Directory at www.childwelfare.gov/nad. Spring 2008

Page 7

Region V News

Many children from abusive or neglectful homes never have the oppor‐

tunity to go on a vacation. So, every year the Jefferson County Foster Parent Associa‐

tion takes children in foster care somewhere special. They choose a location then hold fundraisers throughout the year so that their kids can make fun, unforgettable memories. Foster & Adoptive

Training Conference

This year, the Foster Parent Association treated its kids to a day of fun in the sun on the Kemah Boardwalk. Foster parents Emmie Scott (FPA president), Carolyn Cox (FPA treasurer), Ivy Guidry, Pamela Guidry, Hazel Ste‐

vens, Lark Turner, Helen Brumley and Linda Babbs accom‐

panied the kids, joined by CPS FPA liaison Scheerish McZeal. Save the Date!

12th Annual

Foster and Adoptive

Training Conference

April 17 & 18, 2009

Stephen F. Austin State University

Nacogdoches, Texas 75962

CEUs for LSW, LPC, TAADAC and

LCDC

Foster Parent Training Hours

Conference Sponsors

SFA School of Social Work

Texas Department of Family and

Protective Services

Region V Foster Parent Council

Spring 2008

Page 8

East Texas Heart Gallery

The East Texas Heart Gallery is working hard to help place our children in forever families! Over the last year, 75 children have been photographed for the Web site and tours. Of those children, 30 have been matched with a family, placed in an adoptive home, or consummated their adoption. This spring the Heart Gallery is pleased to announce its newest recruitment initiative called Pure Religion James 1:27. Pure Religion is an exhibit of East Texas Heart Gal‐

lery photos designed to tour through faith‐based congre‐

gations. The exhibit will be displayed in churches, tem‐

ples, synagogues and mosques for up to three weeks. Congregants will then have the opportunity to attend an information meeting at the end of the tour to learn about all the different ways, from donations to volunteer op‐

portunities, that they can help our children . Romelo and Shakyra CPS and private placing agencies will provide informa‐

tion on foster care and adoption. A kick off event is scheduled for Saturday, April 26 from 9 a.m. to noon at Colonial Hills Baptist Church in Tyler. Michael Monroe, pastor of Irving Bible Church and founder of Tapestry, their church’s adoption ministry will be leading seminars focusing on helping local churches start their own foster/

adoption ministry. The public is invited. For more infor‐

mation about Pure Religion, go to www.PureReligionJames127.com. In January 2008, eight young men from Region IV and V attended a photo event with the Tyler Junior College men’s basketball team. The guys had a blast shooting hoops, learning new tricks and hanging out in the locker room! Volunteer photogra‐

phers, videographers and interviewers were assigned to each child to help capture the personality and sparkle that makes each boy shine! Up‐

dating photos and keeping the profiles about each child current is priority for the Heart Gallery, as the response from families increases each time new information is added. Check out the newest photos and children avail‐

able for adoption at www.easttexasheartgallery.com Romelo is 9 and Shakyra is 7. These children are waiting for their forever family. Romelo loves to go to McDonald’s, play basketball and spend time with his sister. He is quiet, patient and eager to please. Shakyra loves to talk and hopes that her forever family will take her to the zoo. She likes to ride her bike, play at the park and go shopping. These children are currently in separate foster homes and desperately seeking a family that will bring them back together again! Learn more about these children at the East Texas Heart Gallery. Page 9

REACHOUT NEWS

Child Welfare Information Center

Diane Sizemore MSW Graduate Assistant Stephen F. Austin State University care of white foster and adoptive parents. As the first black child adopted by a white family in New Mexico, he is very insightful on the special needs of mixed‐race foster and adoptive families. Thank you to all who came to the Reviews on New Resources 11th Annual Foster and Adoptive Conference in February. The Child CWIC has two new DVDs on how to Earn

Welfare Information Center had a Foster Parent improve your foster child’s educa‐

booth set up to inform the confer‐

Training Credit tional experiences. “Working with ence attendees about the resources we have available to Schools,” part of the Foster Parent you as a foster or adoptive parent. I thoroughly enjoyed College collection, and “Endless Dreams: Building Edu‐

meeting all who stopped by the booth to learn about what cational Support for Youth in Foster Care” both deal with the challenges foster children face in the school we have to offer. We had 25 new foster parents sign up system and how you, the foster parent, can help ensure during the conference! We look forward to helping these new patrons, as well as all foster and adoptive parents, ob‐

the child gets the most out of their education. tain the resources they need to enhance their parenting CWIC has received several other DVDs. “Childhood skills and to receive their training hours. Anxiety Disorder,” part of the Foster Parent College se‐

ries, helps foster parents understand their child’s anxi‐

Resources on Parenting Adopted Children ety, root causes, and steps they can take. “ADHD, ADD, To assist foster and adoptive parents struggling with chil‐

& ODD,” another Foster Parent College DVD, gives in‐

dren who have attachment problems, Karyn Purvis, David sight into these disorders and offers advice on how to Cross and Wendy Sunshine’s care for children with these issues. “Calming the Tem‐

book, “The Connected Child: pest: Helping the Explosive Child” provides parents Bring Hope and Healing to with an understanding of children’s angry outbursts Your Adoptive Family,” takes and how to teach the coping skills children need to man‐

a multi‐dimensional approach age their anger and frustration. “Testifying in Court: A based on the latest research, Guide for Child Protective Service Workers” provides covering a spectrum of strate‐

an understanding of court proceedings in dependency gies including attachment ex‐

cases. ercises, behavioral retraining, nurturing touch, sensory inte‐

A special toll free number . . .

gration and nutritional ther‐

(877) 886-6707

apy, to help parents and care‐

. . . is provided for CPS staff and fosgivers heal the childʹs invisible ter and adoptive parents. CWIC

books, DVDs and videos are mailed to

wounds. At the conference, Dr. Purvis was the keynote your home or office, along with a

speaker and taught a workshop. stamped envelope for easy return.

She provided helpful insight into understanding the stress levels Please specify if you are interested in

and attachment problems of chil‐

receiving foster parent training hours, and a

dren in foster and adoptive care. test and evaluation will be included with the

Jaiya John, the speaker for the conference luncheon and youth conference, has written a biogra‐

phy titled “Black Baby White Hands: A View from the Crib.” In this book, he depicts his life as a black child growing up in the book or video. Once completed and returned,

foster parents will receive a letter of verification

of training hours earned.

Your calls are important to us.

We look forward to hearing from you!

(Continued on page 12)

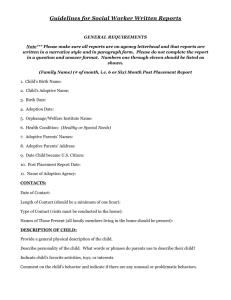

FOSTER PARENT TRAINING - REACHOUT Newsletter Spring 2008

Complete for one hour of training credit and return to your caseworker.

Learning Objectives • The participant will learn about professionals who provide mental health services. • The participant will discuss approaches to therapy provided by adoption therapists. • The participant will identify treatment settings where therapy takes place. • The participant will describe issues that may determine the type of therapy needed. • The participant will learn and discuss the different types of therapy and providers available to help adoptive families. Learning Activities Activity One List three types of professionals that provide mental health services? 1. __________________________________________________ 2._________________________________________________ 3. __________________________________________________ It is important for adoptive families to share openly with their mental health professional that their family includes one or more adopted persons and to inquire about the counselor’s training and experience related to working with adoptive families and adopted persons. (Circle the best answer) True False List and describe two therapy approaches discussed in the article: 1.__________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 2.__________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Briefly discuss three issues that help to determine which therapy approach a mental health professional may recom‐

mend : ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Activity Two In the article, which approach was mentioned as the treatment of choice for families affected by substance abuse? 1.__________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Which approach focuses on rewards and punishments? 2.__________________________________________________________________________________________________________ List four treatment settings in which therapy takes place: 1. _________________________________________________ 2. ____________________________________________ 3_________________________________________________ 4. ____________________________________________ Where do most therapy sessions take place? 1.____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Activity Three If the child is the identified patient, is the family’s involvement in therapy necessary for a positive outcome for the child? (Circle the best answer) Yes No Parents may want to request an evaluation meeting with the therapist ____ to ____ weeks after treatment begins and re‐

quest regular updates thereafter. Evaluation Date ____________ Trainer Child Welfare Professional Development Project, School of Social Work, SFA Name (optional)___________________________________________________________ Newsletter presentation and materials: 1. This newsletter content satisfied my expectations. ___Strongly agree ___ Agree ___Disagree ___Strongly disagree 2. The examples and activities within this newsletter helped me learn. ___Strongly agree ___ Agree ___Disagree ___Strongly disagree 3. This newsletter provides a good opportunity to receive information and training. ___Strongly agree ___ Agree ___Disagree ___Strongly disagree Course Content Application: 4. The topics presented in this newsletter will help me do my job. ___Strongly agree ___ Agree ___Disagree ___Strongly disagree 5. Reading this newsletter improved my skills and knowledge. ___Disagree ___Strongly disagree ___Strongly agree ___ Agree 6. What were two of the most useful concepts you learned? _________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________ 7. Overall, I was satisfied with this newsletter. ___Strongly agree ___ Agree ___Disagree ___Strongly disagree Comments: ______________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Page 12

REACHOUT NEWS

Child Welfare Professional Development Project

Director (Continued from page 1)

for their dedication and support of the confer‐

ence, which is a tremendous professional de‐

velopment opportunity for this area. The SFA School of Social Work is proud to be part of this partnership! From all of us in the Child Welfare Professional Development Project, thanks to all who attended the conference, and we look forward to seeing you at next year’s confer‐

ence. During the conference, Diane, our library assistant, signed up many new foster parents as patrons to the Child Welfare Information Center, and we have been busy with your calls! Be sure to read about new DVDs and books that can be checked out for training hours. Give us a call on the toll free number and let us know how we can support your parenting efforts! Please do not hesitate to call our toll free number if you have any questions or would like to receive some of our resources. Sincerely, Becky We look forward to hearing from you soon!

A few snapshots from the 11th annual Foster and Adoptive Training Conference The CWPDP Director and the registration staff from Angelina College Awards luncheon speaker Jaiya John, Ph. D., CWPDP staff member Linda Johnson, and Canesha Mack, who was the entertainment for the luncheon Dr. Karyn Purvis, keynote speaker; Judy Crone, Region V Foster Parent Council representative; Bernadette Cascio, CVS/FAD program administra‐

tor; and Jackie Hubbard, FAD program director Child Welfare Professional Development Project Staff

Linda Johnson

Graduate Assistant

(936) 468-1846

Kara Easley

Graduate Assistant

(936) 468-4578

Becky Price-Mayo, MSW, LBSW

Director

(936) 468-1808

David Espinosa

Student Assistant

(936) 468-4578

Diane Sizemore

Child Welfare Information Center

(936) 468-2705

Stephen F. Austin State University School of Social Work Child Welfare Professional Development Project P.O. Box 6165, SFA Station Nacogdoches, TX 75962‐6165 REACHOUT NEWS

Spring 2008

Earn One Hour of

Foster Parent Training

Child Welfare Professional Development Project

School of Social Work, Stephen F. Austin State University