English Learners’ Time to Reclassification: An Analysis

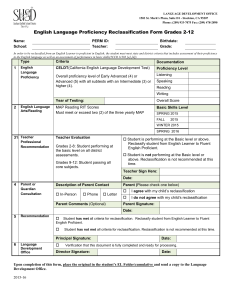

advertisement