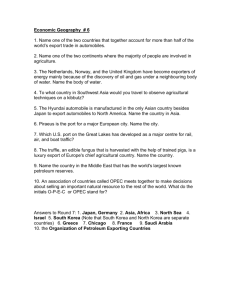

T O L S

advertisement