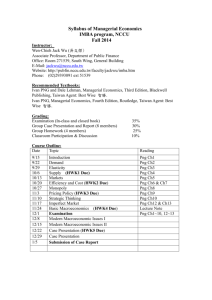

P A U

advertisement