INVESTOR-STATE DISPUTE SETTLEMENT A sequel

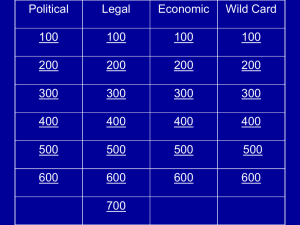

advertisement