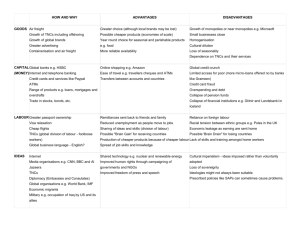

EMPLOYMENT UNCTAD/ITE/IIT/19 UNCTAD Series on issues in international investment agreements

advertisement