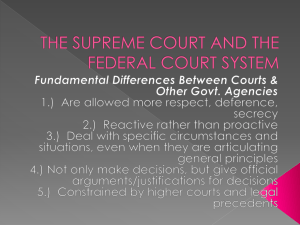

THE NEW JUDICIAL DEFERENCE

advertisement