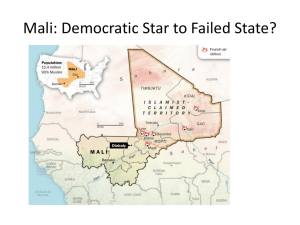

Mali An Investment Guide to Mali Opportunities and conditions October 2006

advertisement