AN INVESTMENT GUIDE TO CAMBODIA Opportunities and conditions September 2003

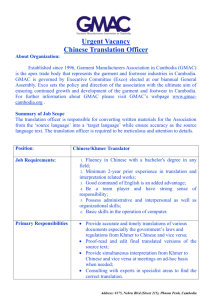

advertisement