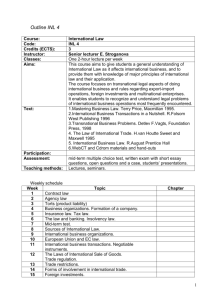

SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY UNCTAD/ITE/IIT/22 UNCTAD Series on issues in international investment agreements

advertisement