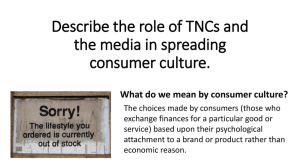

Key messages

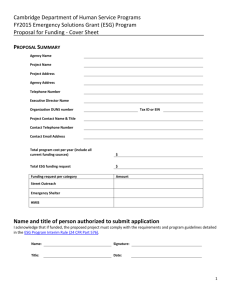

advertisement