Document 10422043

advertisement

Bu yaymm 5846 SaYl1i Flkir ve Sanat Eserlerl

Kanunu'na gore her hakkl Ba~bakanllk Devlet ista­

tlstlk Enstltusu Ba~kanllgl'na alttlr. Ger~ek veya

tUzel kl~lIer tarafmdan Izinslz ~ogaltllamaz ve

dagltllamaz.

ISBN 975 - 19 - 2595 - 9

State Institute of Statistics, Prime Ministry

reserves all the rights of this publication. Unauthorised

duplication or distribution of this publication is prohibited

under Law No: 5846.

Yaym Numarasl

Publication Number 2397

~I iLGiLi l?UBELER - RELATED DIVISIONS

istatlstlkl veri ve bllgl Isteklerl 1~ln

For requests of statistical data and information

Yaym, Haberle~me ve Halkla ill~kller

l?ubesl MudurlUgu

Publications, Communications and

Public Relations Division

+ (312) 418 50 27

+ (312) 417 64 40/213 - 244

+ (312) 417 04 32

+ (312) 425 68 41

Yaym I~eriglne yonellk sorularlnlz 1~ln

For questions of contents about publication

Etut ve Anallz l?ubesl

Analytical Studies Division

T.C. Ba~bakanllk

Devlet istatlstlk Enstltusu

Necatlbey Cad. No: 114

06100 ANKARA 1 TORKiYE

+ (312) 417 64 40/367 - 396

E-posta - E-mail: yayln@dle.gov.tr

internet - Internet : http://www.dle.gov.tr

Kapak tasanml: Sadlk KARAMUSTAFA

Oevlet Istatlstlk Enstltusu Matbaasl - Ankara, Arallk 2000 - State Institute of Statistics, Printing Division, December 2000 MTB: 2000 - 1250 - 1500 Adet - Copies ONSOZ

Yeni binYlhn ba~langlcmda gelecek, bugtintin

He ~ekillenecektir.

ve

ge9mi~in

bilgi ve deneyimlerinin

birle~tirilmesi

nistry

)rised

libited

Ge9tigimiz binytl igerisinde Anadolu topraklan tizerinde dogan, ve bu topraklardan aldtgt

gti9 ile kltalara yaYllan Osmanh imparatorlugu gtintimtize bilim, ktilttir, sanat ve benzeri alanlarda

oldugu gibi istatistik alanmda da zengin bir miras blrakmt~ttr.

istatistik alanmda devraldlglmlz bu zengin mirasl gozler ontine sermenin en iyi yolu Osmanh

Devleti'nde bilgi ve istatistik uretimini, devletin idaresinde kullammmt ve bu konuda olu~an buytik

birikimin igerigini ortaya koymak olarak gortilmektedir.

du~unceden hareketle, ge9mi~imizden gelen ve ancak ytiksek uzmanhk bilgisi ile

mlimklin olan bu engin hazinenin en azmdan bir bolumlinli gun t~lgma 9tkarmak ve bu

gline kadar toplumumuza pek fazla sunulamayan bu birikimi birincil kaynaklara dayah olarak ortaya

koymak amaCl ile "Osmanh Devleti'nde Bilgi ve istatistik" projesinin gergekle~tirilmesine karar

verilmi~tir. <;ok degerli bilim adamlanmlzm katklsl ile olu~an bu 9ah~ma, sadece "Osmanh

Devleti'nde Bilim ve istatistik" konusundaki zen gin birikimi degil, Tlirkiye'de tarih biliminin ula~tlgl

noktaYI da parlak bir ~ekilde gozler online serecektir.

Bu

ula~tlmasl

Projenin gergekle~mesine olanak saglayan Devlet Bakammlz Saym Prof. Dr. Tunca

TOSKAY, Osmanh Devletinin kurulu~unun 700. Yilt kutlamalanndan sorumlu Devlet Bakant Saym

Fikret UNLO ve Ba~bakanhk Mliste~ar Yardimcisl Saym Dr. Flisun KOROGLU'na, projede bu

alandaki 9ah~maslm sunan degerli bilim adamlmlz Prof. Dr. Sevket PAMUK ve haztrlanmasmda

emegi gegen Devlet istatistik Enstittisli'nlin degerli mensuplanna te~ekktirlerimi iletmek isterim.

2

1

Sefik YILDIZELi

Ba~kan

Devlet istatistik EnstitiisU

]

ill

SUNU~

19. Ytizytl oncesi i<rin gtivenilir fiyat ve ticret verileri bulmak, diziler olu~turmak son derece

gti<rrur. Ancak, Osmanh btirokrasisinin defter tutma gelenegi sayesinde, dtinyada <rok az saYlda tilkede

yapllabilecek bir <rah~maYl ger<rekle~tirmek mtimktin oldu. Bu kitapta Devlet istatistik Enstirusti'ntin

destegiyle yedi Yll stiren bir ara~ttrmanm sonucunda olu~turulan 500 Yllhk fiyat ve ticret dizileri, rum

ham malzeme ve kaynaklan ile birlikte sunulmaktadlr. Aynca, okuyuculara ve kullamcllara kolayhk

saglamak amaclyla, olu~turulan dizilerin anlaml hakkmda bir miktar yoruma da yer verilmektedir. Bu

verilerin Osmanh-Ttirkiye iktisadi ve toplumsal tarihi ara~ttrmalannda onemli bir kaynak malzemesi

olarak kullamlacagml, yeni ara~ttrmalar i<rin bir altyapl olu~turacagml umuyorum. Gelecekte

ara~ttrmactlann bu verileri ve dizileri kuJlanarak daha kapsamh degerlendirmeler ve belki de daha

farkh yorumlar yapacaklanna inamyorum.

boyunca yapabileceklerini <rok a~an bir emek birikirni sayesinde

ger<rekle~tirilebildi. Ara~ttrmaya ba~mdan itibaren degerli katkllarda bulunan istanbul Universitesi

ogrencilerinden Figen T ASKIN ile daha sonra <re~itli a~amalarda kattlan Marmara Universitesi

ogrencilerinden Seda BAYINDIR ve Haydar <;:ORUH, Londra Universitesi ogrencilerinden Ahmet

AKARLI, Binghamton Universitesi ogrencilerinden Nadir OZBEK, Bogazi<ri Universitesi

ogrencilerinden Cern EMRENCE, Cenk ERKiN, Bagl~ ERTEN, Rasim OZCAN, I~lk OZEL, Funda

SOYSAL, Cenk T ARHAN ve Emre Y AL<;:IN'a <rok te~ekktir bon;luyum.

Bu

<rah~ma

bir ki~inin

ya~aml

<;:ah~maya temel olu~turan veriler btiytik <rogunluguyla istanbul'da Ba~bakanhk Osmanh

Ar~ivleri ile Topkapl SaraYl, istanbul Mtifttiltigti ve Dolmabah<re SaraYl Ar~ivleri'nden derlenmi~tir.

Gosterdikleri kolayhk ve yardlmlardan dolaYl bu ar~ivlerin yonetici ve <rah~anlanna te~ekktir

bor<rluyuz. Aynca <rah~mamn <re~itli a~amalannda Prof. Dr. Halil SAHiLLiOGLU ile Prof. Dr. Robert

ALLEN'm gorti~lerinden yararlandlm. Dr. Nadide SE<;:KiN kimi kaynaklara ula~mamda yardlmcl

oldu. Prof. Dr. Edhem ELDEM, Dr. Mehmet GEN<;:, Do<;. Dr. Osman SARI ve Prof. Dr. Zafer

TOPRAK projenin on sonu<rlanm dinleyerek degerli ele~tirilerde bulundular. Son ti<r Yll i<rinde

ara~ttrmamn sonu<rlanm Ttirkiye'de ve yurtdl~mda <re~itli bilimsel seminer ve kongrelerde sunma ve

tartl~maya a<rma flrsatt buldum. Bu toplanttlarda gorti~ belirten, katklda bulunan degerli

meslekda~lanma te~ekktir bor<rluyum. <;:ah~ma Bogazi<ri Universitesi Atarurk Enstirusti ve Ekonomi

Boltimti ile Bogazi<ri Universitesi Ara~ttrma F onu Projeleri 97HZ 101, 99HZ02 ve aynca Ttirkiye

Bilimler Akademisi tarafmdan da klsmen desteklenmi~tir. Bu degerli kurumlara da te~ekktir ederim.

Devlet istatistik Enstirusti'nde tarihi istatistik <rah~malanm ba~latan, 1994 Ylhndan bu yana

Tarihi istatistikler Dizisi adl altmda bir dizi cildin yaymlanmasma onctiltik eden ve ytllar boyunca

destek saglayan DiE eski ba~kam Saym Prof. Dr. Orhan GUvENEN ile diger degerli eski ba~kanlar

Saym Prof. Dr. Mehmet KAYT AZ, Saym Mehmet ENSARi ve Saym Prof. Dr. Orner

GEBiZLiOGLU'na ve nihayet goreve ba~ladlgl gtinden bu yana bu kitabm yaYlmlanmasl i<rin gerekli

kurumsal destegi esirgemeyen Devlet istatistik Enstirusti Ba~kam Saym Sefik YILDIZELi'ne te~ekktir

bor<rluyum. Onlann yardlmlan olmadan bu degerli kurumun <rattsl altmda tarihi verilere dayanan bu

denli geni~ bir <rah~mamn yapllmasl mtimktin olamazdl. Son olarak da kitabm yayma hazlrlanmasmda

emegi ge<ren ttim Devlet istatistik Enstirusti mensuplanna saygtlanml ve minnet duygulanml iletmek

isterim.

Prof. Dr.

v

~evket

PAMUK

iC;iNDEKiLER

CONTENTS

Sayfa

Onsoz............................................................. Page

III

Preface. ......... ..... ....... .................. ...............

III

Prof. Dr. Sevket P AMUK............................ V

Introduction

Prof. Dr. Sevket P AMUK..........................

V

ingilizce Ozet................................................ IX Summary in English.... .............. ................

IX

List of Graphs...................................... .....

XVII

List of Tables..................... .......................

XX

Sunu~

Grafik Listesi................................................ XVII Tablo Listesi................................................. XX Chapter I

Boliim I istanbul'da Tfiketici FiyatJan, 1469-1998.. 1

Consumer Prices in Istanbul,1469-1998 ....

BOIiim II Chapter II

istanbul Tfiketici Fiyatlan Endekslerine ili~kin Daha AyrIOtIlI Veriler...................... More Detailed Information About the

Consumer Price Indices for IstanbuL.....

37

51

Boliim IV

Prices in Other Cities, 1489-1998..............

51

Chapter IV

istanbul'da Ucretler, 1489-1922 ................. 61

Wages in Istanbul, 1489-1922................. ..

61

Chapter V

Boliim V Diger Kentlerde Ucretler, 1489-1996........ .. 75

Boliim VI

Avrupa

37

Chapter III

Boliim III Diger Kentlerde Fiyatlar, 1489-1998......... 1

Wages in Other Cities, 1489-1996 .......... ..

75

Chapter VI

ve Ulkeleri

He

Kentleri

1450-1992.............................

Kar~da~tlrma,

87

Comparisons with European Cities and

Countries, 1450-1992..... ........ .............. .....

87

Ek Tablolar................................................... 99

Appendix Tables.. ............ .................. ........

99

Kaynak~a...................................................... 207

Bibliography..............................................

207 VII SUMMARY IN ENGLISH

Utilizing a large volume of archival documents, this volume establishes for the first time,

the long-term trends in consumer prices and wages of skilled and unskilled construction workers in

Istanbul and more generally around the Eastern Mediterranean from the second half of the fifteenth

century until World War I. These series are then inserted into a larger framework of price and wage

trends in European cities during the same period.

Prices

We begin with a summary discussion of the methodology and then present the basic results

of a recently completed study on prices and wages in Istanbul, and to a lesser extent in other

leading cities of the Ottoman Empire, from the fifteenth to the twentieth century.

The study on prices has utilized data on the prices of standard commodities (food and non­

food items) collected from more than six thousand account books and price lists located in the

Ottoman archives in Istanbul. In the first stage of the study, three separate food price indices were

constructed. One of these is based on the account books and prices paid by the many pious

foundations (vaklt), both large and small, and their soup kitchens (imaret). Another index is based

on the account books of the Topkapi palace kitchen and the third utilizes the officially established

price ceilings (narh) for the basic items of consumption in the capital city.

To the extent possible, standard commodities have been used in the construction of these

indices in order to minimize the effects of quality changes. Each of the three food indices includes

the prices of ten to twelve leading items of consumption, namely flour, rice, honey, cooking oil,

mutton, chick peas, lentils, onions, eggs, sugar (for the palace only), coffee (beginning in the

seventeenth century for the palace and eighteenth century for the pious foundations) and olive oil

for burning. Amongst these, flour, rice, cooking oil, mutton, olive oil and honey provided the most

reliable long term series and carried the highest weights in our food budget. In cases where the

prices of one or more of these items were not available for a given year, the missing values were

estimated by an algorithm that applied regression techniques to the available values.

Since the availability and quality of price observations varied over time for most of the

foodstuffs in our list, the four hundred year period until 1860 was divided into five sub-periods and

indices were calculated separately for each. In each sub-period some commodities had to be

excluded from the index due to the unavailability of price observations. The weights of the

individual commodities was kept constant as long as they were included in the index.

Based on the available evidence regarding the budget of an average urban consumer, the

weight of food items in the overall indices was fixed between 75 and 80 percent. The weight of

each commodity in the overall index was then based on the shares of each in total expenditures of

the respective institutions. To cite two prominent examples, in the absence of long series on bread

prices, the weight of flour, mostly wheat flour, varies mostly between 32 and 40 percent of food

expenditures and 24 to 32 percent of overall expenditures, depending on the fluctuations in prices.

Similarly, the weight of meat (mutton) varies between 5 and 8 percent of the overall budget. It is

likely that the diets of private households in the capital city differred from those offered by the

soup kitchens. At this stage, however, it is not possible to approximate the private diets more

closely.

The medium and long term trends exhibited by the three food price indices are quite

similar. This is confirmed by the separate indices constructed from the prices of five commodities

appearing in all of three of these sources for the period 1469 to 1863. Nonetheless, because the

palace and narh prices might be considered as official or state controlled prices, the study gives

greater weight to the indices based on the prices paid by the soup kitchens, and more generally, the

pious foundations.

In the second stage, prices of non-food items obtained from a variety of sources, most

importantly the palace account books, were added to the indices. These commodities are soap,

IX -

wood, coal, nails by weight (used in construction and repairs). From the various account books of

the imperial palace, it is possible to obtain long term price series on two types of woolen cloth, the

locally produced yuha and the ¥uha Londrine imported from England. Both the absolute level and

long term trends in the more reliable woolen cloth prices suggest, however, that these were not the

varieties worn by ordinary people but expensive types of cloth purchased by high income groups.

Since increases in the prices of these woolen varieties lagged far behind the overall index, cloth

prices were not included in the overall index until 1860. Price data for a large number of other

types of cloth have also been collected but none of these are available for long periods of time. A

cost of living index should also include rental cost of housing but an adequate series for standard

housing is not available at this stage.

For the period 1860 to 1914, data from the palace, vaklf and narh sources are very limited.

For this reason, the detailed quarterly wholesale prices of the Commodity Exchange of Istanbul

covering about two dozen commodities were used. Indices based on these prices were then linked

to those covering the earlier period.

Istanbul was chosen primarily because the data was most detailed for the capital city.

However, price data from the account books of the pious foundations is available for other cities of

the empire. Price observations from a shorter list of commodities was used to construct separate

indices for the cities of Edirne, Bursa and Damascus. These indices indicate clearly that prices in

other OUoman cities moved together with those in Istanbul for the period for which comparable

data is available. In these cities, both the overall change in the price level from 1490 to 1860 and

the two major jumps in the price level that occurred late in the sixteenth and early in the nineteenth

century were broadly comparable to the price trends in Istanbul. In addition, detailed price series

gathered by Andre Raymond for 17th and especially 18th century Cairo indicate that, even though

the monetary units were not identical, prices expressed in grams of silver showed similar trends in

Istanbul and Cairo.

We have thus obtained for the first time for the Middle East, in fact for the first time for

anywhere in the non-European world, detailed and reliable price series for these four and a half

centuries. For Istanbul, the results have been extended from 1914 to tile present since published

data on consumer prices is readily available for the recent period.

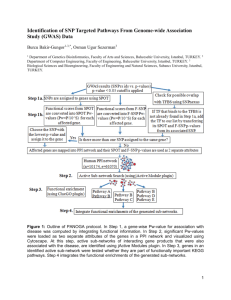

Graph 1.1 shows the annual values of the overall price index that combines the food prices

obtained from the account books of pious foundations with the prices of non-food items. The

vertical axis is given in log scale so that the slope of the line indicates the rate of change of nominal

prices. These results indicate that prices increased by a total of about 300 times from 1469 until

World War L This overall increase corresponds to an average increase of 1.3 percent per year for

the entire period.

The indices show that Istanbul experienced a significant wave of inflation from the late

sixteenth and to the middle of the seventeenth century when the prices increased by about five fold.

This is the period usually associated with the Price Revolution of the sixteenth century. The indices

also show, however, that there occurred a much stronger wave of inflation beginning late in the

eighteenth century and lasting into the 1850's when the prices increased by 12 to 15 times. Most of

the latter increases were associated with the debasements that began in the 1780's and accelerated

during the reign of Mahmud II (1808-1839). In contrast, the overall price level was relatively stable

from 1650 to 1780 and from 1860 until World War I.

Having established the basic trends in prices, we will briefly consider the causes of

Ottoman inflation during these centuries. Obviously there were many causes of inflation during the

early modem period as evidenced by the large literature and the extensive debates on the subject.

From the long term perspective offerred by these price indices and our study of the Ottoman

currency, however, there is strong evidence that debasements or the reduction of the specie content

of coinage by the monetary authorities were the most important cause of Ottoman price increases.

The relation between debasements and the price level can be established more closely by

following the silver content of the Ottoman currency since 1450. Graph 1.2 presents the annual

silver content of the akye and later the kuru~ (linked at 1 kuru~= 120 akyes) based on an earlier

x

>oks of

)th, the

reI and

not the

~roups.

:, cloth

f other

ime. A

andard

imited.

;tanbul

linked

tl city.

ities of

~parate

ices in

)arable

60 and

~teenth

: series

though

~nds in

me for

a half

)lished

prices

s. The

:>minal

9 until

ear for

le late

e fold.

ndices

in the

lost of

lerated

stable

ses of

ng the

lbject.

toman

ontent

tses.

ely by

mnual

earlier

study.(Pamuk 1999a also available in English from Cambridge University Press.) The vertical axis

is again in log scale so that the slope of the curve indicates the rate of debasement. Graph 1.2

shows that the silver content of the Ottoman currency declined most rapidly during the late

sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries and also during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth

centuries. In contrast, prices were relatively stable after 1860 when the silver content of the

Ottoman currency remained unchanged.

An alternative way to examine the relationship between debasements and the price level

would be to construct price indices expressed in grams of silver which is obtained by multiplying

the value of the price index by the silver content of the Ottoman currency for the same year. Graph

1.3 combines the evidence in the earlier two graphs and presents the overall price index for Istanbul

in grams of silver. The series was extended beyond 1870 even though world silver prices declined

sharply after that date, because the nominal value of silver coinage was not changed under the

Ottoman monetary system until World War I.

It is remarkable that even though nominal prices in Istanbul increased by about 300 times,

prices expressed in grams of silver stayed within the relatively narrow range of 1.0 to 3.0 during

these four and a half centuries. There were medium term movements in prices expressed in grams

of silver. They increased from 1500 until 1640, declined until the early decades of the eighteenth

century, and increased again until the middle of the nineteenth century. All this, however, occurred

around a long-term trend which was rising only modestly. In other words, debasements were the

most important determinant of Ottoman prices in the long term. In the longer term, the so-called

silver inflation also contributed to the changes in the overall price level but its impact paled in

relation to that of debasements.

Detailed indices on the prices of basic foodstuffs expressed in grams of silver and the terms

of trade between foodstuffs and manufactured goods have also been calculated from the Istanbul

data base. (See graphs in Chapter 2)

Wages

In this second part of the study, daily wage data were gathered from several thousand

account books of the construction and repair sites in Istanbul and other cities. These account books

contain daily wages for both unskilled and a variety of skilled construction workers. Urban

construction workers was a relatively homogeneous category of labor over time and space.

Moreover, in contrast to the payments made to other employees, urban construction workers

received a high proportion if not all of their pay in cash rather than in kind or in the form of shelter,

food and clothing. As a result, their wages allow for useful inter-country comparisons between pre­

industrial societies.

The construction account books prepared by the state or by pious foundations of varying

size and utilized for the purposes of this study usually consisted of a series of attendance records

listing the workman employed, craft of the worker, his rank (master, common laborer etc.) and the

wages paid to each. Sometimes the accounts provide a separate record for each day; sometimes a

few days or weeks are covered by a single attendance sheet. Many of the account books also

included lists and prices of materials purchased such as iron, lime and nails the last of which was

utilized in the construction of the price indices.

Information about the length of the workday is rare in these records. Similarly, information

regarding whether food or lunch is provided along with the daily wage is usually not given. For that

reason, we have chosen to ignore those aspects of the daily wage. We have also decided to ignore

the seasonal variations in daily wages. In any case, the overwhelming majority of the available

observations belong to the construction season (April through October in Istanbul).

The wages for unskilled workers referred mostly to one type of worker, called lrgad in the

early period and ren!a'ber after about 1700. In contrast, daily wage rates could be found in for more

than half a dozen categories of skilled construction workers in these account books. In order to

utilize the additional information, an index was constructed for skilled wages which included the

wages of carpenters, masons, stonecutters, ditchdiggers, plasterers and others. Based on the relative

XI frequency with which they appeared in the account books, the greatest weight in this index was

given to the category of ~, specialists who built wooden houses and the wooden parts of

buildings. There also existed a separate category of carpenter (marangoz) which apparently referred

more to makers of furniture. The share of neccar fluctuated between 50 to 60 percent in our skilled

wage index.

It is not easy to judge at this stage to what extent daily wages were influenced by

institutional factors and to what extent they were determined by market forces. However, the fact

that during periods of rapid debasement real wages initially declined but adjusted upwards fairly

quickly suggests that the process of wage formation was open to market forces.

Graph 4.3 presents real daily wage series for skilled and unskilled construction workers

obtained by deflating the nominal daily wage series by the consumer price index for the city of

Istanbul. For both the skilled and unskilled real wage series in this graph, the base years 1489-90

are set at l.0.

These indices indicate that real wages of unskilled construction workers in Istanbul

declined by 30 to 40 percent during the sixteenth century. Population growth must have been the

most important determinant of this trend. After remaining roughly unchanged until the middle of

the eighteenth century, Istanbul real wages increased by about 30 percent from late eighteenth until

mid-nineteenth century and then by another 40 percent during the late nineteenth and early

twentieth century. On the eve of World War I, real wages of unskilled construction workers were

about 20 percent above their levels in 1500. Because the skill premium rose during the nineteenth

century, real wages of skilled workers stood at approximately 50 percent above their levels in 1500.

The purchasing power of the daily wages of both the skilled and unskilled workers were

reasonably high during these four and a half centuries. During the sixteenth century, an unskilled

construction worker could purchase with his daily wage 8 kilos of bread or 2.5 kilos of rice or more

than 2 kilos of mutton. Daily wages of skilled workers were 1.5 to 2 times higher. At these levels of

daily pay, skilled construction workers must have enjoyed standards of living well above the

average for the population as a whole and also above the average of the urban areas even if they did

not work for as many as 200 days per year.

It needs to be kept in mind, however, that most of our knowledge about the wages of

construction workers has been based upon state records and records of the medium sized and larger

pious foundations. These larger institutions could seek out the best craftsmen and pay wages in

cash rather than in kind and at more consistent rates than the smaller employers.

Graph 4.3 also makes it possible to follow over time the skilled/unskilled wage differential

or the wage premium for skilled labor. After declining during the sixteenth and seventeenth

centuries, this premium began to increase in the second half of the eighteenth century in Istanbul

reaching its peak on the eve of World War I. Not only changing demand but also decline in supply

due to the emigration of skilled construction artisans must have contributed to this important trend.

It was also after 1750 that prices of essentials such as flour, meat, milk, eggs and wood

began to rise much faster than the overall index while the prices of sugar, coffee and imported cloth

which were consumed by the higher income groups began to lag behind. As mentioned earlier, this

divergence further widened the difference between the purchasing power of skilled and unskilled

laborers. This differentiation may be interpreted as one of the early consequences of globalization.

We were also able to collect data on the daily wages of construction workers, both skilled

and unskilled, in other Ottoman cities around the Eastern Mediterranean including the Balkans for

the same period, 1489 to 1914. These observations were obtained from the account books of the

pious foundations operating in these cities and are available from the Ottoman archives in Istanbul.

They show clearly that nominal wages in other Ottoman cities also increased by more than 300 fold

during this period. More interesting for our purposes would be to establish nominal wage trends in

other cities in relation to Istanbul, and more specifically to find out whether there emerged a gap

between the nominal wages of Istanbul and those of other cities during these centuries. Daily wages

in Bursa and Edirne, two cities that had served as Ottoman capitals before Istanbul and that were

XII ex was

larts of

eferred

skilled

~ed by

he fact

s fairly

1I0rkers

city of

489-90

stanbul

een the

ddle of

th until

:l early

rs were

.eteenth

n 1500.

rs were

Iskilled

Jr more

~vels of

Jve the

hey did

ages of

d larger

'ages in

erential

:nteenth

[stanbul

I supply

t trend.

d wood

ed cloth

ier, this

nskilled

mtion.

1 skilled

leans for

s of the

stanbul.

300 fold

rends in

:d a gap

y wages

lat were

close to it geographically, were quite comparable and occasionally higher than those of Istanbul

during the sixteenth century when the latter was still modest in size at 100,000 to 200,000. With the

growth of Istanbul over time, however, the nominal wage gap between it and the other urban

centers began to widen. Graphs 5.3 and 5.4 follow the nominal wage differentials between Istanbul

and the second-tier urban centers of the empire. The wage gap between Istanbul and the smaller,

third-tier urban centers was even greater. Evidence from other sources also indicate that during the

second half of the nineteenth century, nominal wages in Istanbul were, on the average, 40 to 50

percent higher than those in other Ottoman cities. (Boratav et. aI., 1985)

Comparisons across Europe

In a recent study of prices and wages in European cities from the Middle Ages to the First

World War, Robert Allen utilizes a large body of data most of which was compiled during the early

part of this century by studies commissioned by the International Scientific Committee on Price

History founded in 1929. In order to facilitate comparisons, he has converted all price and wage

series into grams of silver and chose as a base the index of average consumer prices prevailing in

Strasbourg during 1700-49. (Allen, 1998)

Allen argues that even though wages in a single city may be accepted as a barometer of

wages in the whole economy, international comparisons need to be made between cities at similar

levels in the urban hierarchy. Since his study uses data from cities at the top of their respective

urban hierarchies such as London, Antwerb, Amsterdam, Milan, Vienna, Leipzig and Warsaw, it

would make sense to insert Istanbul, another city at the top of the urban hierarchy of its region, into

this framework. It is not very difficult to do so since prices and wages were already expressed in

grams of silver in the present study. However, it was still necessary to express Istanbul prices in

terrns of the Allen base of Strasbourg 1700-49=1.0. For this purpose, Ottoman commodity prices

for the interval 1700-49 were applied to Allen's consumer basket with fixed weights. A second and

equally useful method of linking Istanbul's price level to those of other European cities in the Allen

set was to employ the detailed annual commodity price series gathered by Earl Hamilton for

Valencia and Madrid for 1500 to 1800 and compare them with the Istanbul prices for the same

commodities. Since Valencia and Madrid prices were already calibrated into the Allen set, it was

then possible to determine the Istanbul price level vis-a-vis European cities for each interval. The

price series for flour, mutton, olive oil, cooking oil, onions, chick peas, pepper, sugar and wood

were used in these calculations. The two procedures produced results that were quite similar. They

are shown in Graph 6.1.

The insertion of Istanbul prices into this framework raises some questions and leads to a

number of interesting observations. First, Allen's data set indicates that during the first half of the

sixteenth century, before the impact of the Price Revolution began to be felt, south European prices

were higher than those elsewhere in Europe. Similarly, our indices show that early in the sixteenth

century, prices in Istanbul were higher than prices in all of the sixteen cities covered by Allen.

Secondly and relatedly, the rise in Istanbul prices expressed in grams of silver was slower than

elsewhere in Europe during the era of the Price Revolution until 1650. As a result, Istanbul prices

expressed in grams of silver tended to converge with those in other Mediterranean and European

cities, with the exception of Spain where prices rose fastest and remained higher than anywhere

else in Europe.

Thirdly, Allen's series indicate that despite the huge growth in trade, the spread of

European prices expressed in grams of silver was just as wide as on the eve of World War I as it

had been in 1500. European prices and price disparities began to increase after 1800 with London

leading the way. Istanbul prices expressed in grams of silver began to rise in the second half of the

eighteenth century but lagged behind other European cities during the nineteenth century. On the

eve of World War I, Istanbul prices in grams of silver or gold were comparable to but lower than

all the other cities in the Allen set.

Istanbul and other Ottoman port cities remained linked to other European ports during

these four centuries through the Black Sea and especially the Mediterranean. In the future, it would

XIII be useful to examine the issue of price integration more closely by applying statistical techniques to

the annual Istanbul and other European price series.

Our indices show that daily wages in Istanbul and other Eastern Mediterranean cities

expressed in grams of silver were comparable to many other locations in northern and southern

Europe in the early part of the sixteenth century. However, because Istanbul prices were higher

than all other cities in Allen's sample, real wages in Istanbul varied between 60 and 90 percent of

real wages in other cities during that period.

Wages as an Indicator of Standards of Living

Istanbul real wages increased by about two thirds from the last quarter of the eighteenth

century until World War I. As a result, the gap in real wages between Istanbul and other cities in

northwestern Europe, London, Antwrb, Amsterdam, and Paris appears to have widened after the

Industrial Revolution but less than one might have expected. On the eve of World War I, real

wages of unskilled workers in London were 2.7 times greater than those in IstanbuL Graph 6.2

shows that real wages of unskilled workers in Amsterdam were 90 percent higher and Paris wages

were 60 percent higher than those in Istanbul during 1900-13.

While these results are broadly in line with our expectations, a comparison with the

purchasing power parity (PPP) adjusted GDP per capita series recently constructed by Angus

Maddison reveal differences that are not insignificant. The Maddison series show that per capita

GDP differences between Turkey on the one hand and United Kingdom, France, the Netherlands

and Italy on the other were wider than the differentials in the real wages of unskilled construction

workers in the leading cities of of each pair of countries. The PPP adjusted per capita GDP

estimates by Maddison point to a 1 to 5 gap between Turkey and the United Kingdom; 1 to 3.8 gap

between Turkey and the Netherlands: and 1 to 3 gap between Turkey and France. The same series

indicate that PPP adjusted per capita GDP in Italy was 2.3 times higher than that of Turkey. In

contrast, Istanbul real wages were close to but higher than those of Florence and Milan in 1900-13.

In short, the gap in PPP adjusted per capita GDP between Turkey and these European

countries on the eve of World War I appears, on the average, to be twice as high at the real wage

gap between Istanbul and the leading cities in these countries. This is an interesting and potentially

important divergence that needs to be examined further.

Part of this divergence may be due to errors of measurement in the available series. We

doubt, however, that these improvements in the available series can eliminate the divergence

between the urban real wage and per capita GDP series. Instead, we think there are a number of

other factors all or most of which contributed more significantly to this divergence.

First, there were important differences between the nominal wages of construction workers

in Istanbul and those of other Ottoman cities. During the second half of the nineteenth century and

up to World War I, Istanbul wages were, on the average, 40 to 50 percent higher than nominal

wages in other cities within the borders of modern Turkey. In contrast, official data on the prices of

essentials indicate that in 1913-14 prices of essential commodities purchased by the consumers

were closer to each other appeared to be lower in Istanbul than the average of the 20 leading cities

within Turkey.

Secondly, there is evidence for a growing scarcity of labor in urban areas during the second

half of the nineteenth century until World War L With its low population density, Anatolia was a

labor scarce, land abundant area until the middle of the twentieth century. These factor proportions

supported small peasant ownership and production. Landless peasants became sharecropping

tenants and wage labor in agriculture remained limited to seasonal labor for specific crops. The

availability of land and the prevalence of small peasant production may have slowed down rural­

urban migration and contributed to labor shortages in the urban areas.

These urban-rural differences combined with the regional differences or Istanbul vs. the

rest gap mentioned above to create large differences between per capita nominal income levels of

the Istanbul region and the rest of the country. Vedat EIdem's estimates indicate that on the eve of

XIV lues to

World War I. per capita income levels of the Istanbul region, which was mostly but not entirely

urban, were twice as high as the average for the Ottoman Empire as a whole.

cities

luthem

higher

:ent of

All this suggests that the daily wages of urban construction workers in the Ottoman Empire

may have been high in relation to the underlying per capita income, at least in comparison to the

western and northern European context. We doubt that the divergence between the available urban

real wage and per capita GDP series for Istanbul and the Ottoman Empire can be eliminated by

developing more reliable real wage and/or per capita GDP series. Instead, this divergence should

caution us about using daily wages of construction workers in a leading city or more generally in

the urban areas as indicators of the standards of living for an entire country.

lteenth

ities in

:ter the

I, real

Iph 6.2

wages

The volume also presents detailed nominal and real wage indices for workers in Turkey's

manufacturing industry since 1914. These series indicate that real wages in Turkey remained below

their 1914 levels until the 1950s but showed a strong upward trend from 1950 to the end of the

1970s, increasing by three fold in three decades. Nonetheless, a comparison with similar real wage

series for some of the Western European countries suggest that the wage gap between Turkey and

the leading European countries did not close during the twentieth century. If anything, that gap

appears to have widened since 1914. (Graphs 5.5 and 6.4)

I

ith the

Angus

. capita

erlands

ruction

a GDP

3.8 gap

! series

key. In

00-l3.

lropean

U wage

entially

es. We

!rgence

nber of

I{orkers

lIry and

lominal

rices of

lsumers

g cities

second

a was a

)Qrtions

ropping

ps. The

n rural­

vs. the

!vels of

~ eve of

xv GRAFiK LisTESi

Grafik LIST OF GRAPHS

Sayfa

Boliim I 1.1 istanbul tiiketici fiyatlarl endeksi, 1469-1914, [1469=1,0]......................

1.2 Page Chapter I 1.1

9

Ak~enin giimii~ i~erigi,

1469-1914,. [gram]...............................................

10 1.3 istanbul'da tiiketici fiyatlan, 1469­

1914, Gram giimii~, [1469=1,0)......

Graphs

Consumer price index for Istanbul,

1469-1914, [1469=1,0] .............. .

9

1.2

Silver content of the akge, grams,

1469-1914............................. .

1.3 Consumer price index for Istanbul, grams of silver,

1469-1914, [1469=1,0]....................... .......

11 Consumer price index for Istanbul, 1910-1998, [1914=1,0]................. 20 11 10

1.4 istanbul'da

tiiketici

fiyatlarl endeksi,1910-1998, [1914=1,0].......

20 1.4 1.5 istanbul'da tiiketici fiyatlannm ytlhk degi~im oram, 1910-1998.......

21 1.5 Boliim II Chapter II 2.1 istanbul'da glda mallan fiyat endeksi, 1469-1914, [1469=1,0].......

40 2.1 2.2 istanbul i~in glda mallan fiyat endeksleri,1469-1863, [Valuf, saray ve narh fiyatlarl, saray, 1469=1,0]

41 2.2 Food price indices for Istanbul, pious foundations, palace and narh official ceiling) prices, 1469-1863, [1469=1,0].......... ........... ......... 41 2.3 istanbul'da temel glda mallannm fiyatlarl, 1700-1850, [Valuflar ve ozel harcama defterleri, 1469=1,0].

42 2.3 Prices of basic foodstuffs m Istanbul, from pious foundations and account books of private individuals, 1700-1850, [1469=1,0]

42 2.4 istanbul'da temel glda mallarmm fiyatlan,1489-1914, [Un, gram giimii~)............................

43 2.4 Prices of basic foodstuffs in Istanbul, flour prices in grams of silver, 1489-1914....................... 43 2.5 istanbul'da temel glda mallannm fiyatlan,1489-1914, [Koyun eti ve pirin~, gram giimii~ ) 44 2.5 Prices of basic foodstuffs in Istanbul, mutton and rice prices in grams of silver, 1489-1914............ 44 2.6 istanbul'da

temel

tiikedm mallanmn fiyatlarl, 1489-1914, [Bal, zeydnyagl, sadeyag ve odun, gram giimii~I....................................

45 2.6 Prices of basic consumer goods in Istanbul, honey, olive oil, cooking oil and wood for burning, prices in grams of silver, 1489-1914........... 45 Annual rate of change of consumer prices

in

Istanbul,

percent, 1910-1998.......................................

21 Food price index for Istanbul, 1469­

1914, [1469=1,0]......................

40 46 XVII Grafik

Sayfa

2.7 istanbul'da

glda

mallarmm

fiyatlan,1489-1914,

[Kabve ve ~eker, gram giimii~]........

Page

Graphs 2.7

Prices of basic consumer goods in

Istanbul, coffee and sugar prices in grams of silver, 1489-1914 .............. 46 2.8 istanbul'da glda mallan/mamul mallar fiyat oraDl, 1489-1914, [1489-1490=1,0]................................ 47

2.8

Food prices! manufactured goods

prices ratio for Istanbul 1489-1914, [1489-1490=1,0].............................. 47 BOliimIII

Chapter III 3.1 Osmanh kentlerinde glda mallarl fiyatlan, 1469-1864, (istanbul 1469=1,0]......................... 54

3.1 Kabire ve istanbul'da glda mallan fiyat endeksi, 1624-1798, (Gram giimii~; 1690=1,0]............... 3.2

3.2 3.3 3.4 46

55

Ankara'da

tiiketici

fiyatlan

endeksi,1914-1998,

[istanbul 1914=1 ,0].........................

56

Ankara'da tiiketici fiyatlannm

yIlhk degi~im oraDl, 1914-1998......

57 3.3

3.4

BOliim IV 4.1 4.2 4.3 5.2 Food price indices for Cairo and

Istanbul, in grams of silver, 1624­

1798. [1690=1,0]......................

55 Consumer price index for Ankara,

1914-1998. [Istanbul 1914=1,0]..........................

56 Annual rate of change of consumer

prices

in

Ankara,

percent, 1914-1998........................................ 57 istanbul'da in~aat i~lYilerinin giinliik

iicretleri,

1489-1914, 66

[Ak~e] ••••...••••..•••••..••••...••••...•.•.....••.. 4.1 istanbul'da

in~aat

i~lYilerinin

giinliik

iicretleri,

1489.1914,

[Gram gumu~] ............................... .

4.2

Daily wages of construction

workers in Istanbul, grams of silver, 1489-1914........................................ 67 4.3 Purchasing power of the daily

wages of construction workers in

Istanbul,1489-1914, [1489-1490=1,0]...............................

istanbul'da in~aat i~lYilerinin

giinliik iicretlerinin satm ahm

giicii, 1489-1914, [1489-1490=1,0].

Osmanh kentlerinde diiz i~IYUerin

(Irgad) giinliik iicretleri,

1489-1914, [ak~e]............................

kentlerinde

vasdll

(neccar) giinliik iicretleri,

1489.1914, [ak~e]............................

67

68 Chapter V 5.1 Daily

wages

of

unskilled

construction workers (lrgad) in

Ottoman cities, 1489-1914, [ak~e] ...

5.2

Daily wages of skilled construction

workers (neccar) in Ottoman cities, 1489-1914, [ak~e] ....................... 5.3 Daily

wages

of

unskilled construction workers (lrgad) In Ottoman

CIties,

1489-1912, [for each year, Istanbul=1 ,0] ........... . 79

Osmanh

Osmanh kentlerinde diiz i~~ilerin (Irgad) giinliik iicretleri, 1489-1912, [Her yd i~in istanbul=I,O]............. Daily wages of construction

workers in Istanbul, 1489-1914, [Ak~e]...............................................

i~~ilerin

5.3 54 Chapter IV BOliim V 5.1 Prices of foodstuffs in Ottoman

cities, 1469-1864, [Istanbul 1469=1,0]..........................

80

81 XVIII 66 68 Page

)ds in

ces in

Grafik

5.4 5.5 47 6.1 54 o and 1624­

55 nkara,

5.4 Daily wages of skilled construction workers (neccar) in Ottoman cities, 1489-1912, [for each year, Istanbul=l,O]............ 82 Tiirkiye imalat sanayiinde i~~i

iicretlerinin satm ahm giicU,

1914-1996, (1914=1,0]....................

5.5 Purchasing power of manufacturing industry wages in Turkey, 1914­

1996, [1914=1,0].............................

83 83 uction 1-1914, 66 uction

.silver,

6.1 Consumer

price

indices

for European

cities,

1450-1913; [prices III grams of silver , Strasbourg,1700-1749=1,0].......... 90 90 Avrupa kentlerinde dUz i~t;i iicretlerinin satm ahm gilcii, 1450-1913, gumu~

cinsinden [Gram

iicretler/tUketici fiyatlan endeksi1 91 6.2 Purchasing power of the wages of unskilled construction workers III European

CItIes,

1450-1913, [wages in grams of silver / consumer price index]...................... 91 6.3 Avrupa kentlerinde vaslfh i~~i iicretlerinin satlD ahm gilcii, 1450-1913, [Gram giimii~ cinsinden iicretler/ tuketici fiyatlan endeksi ]............. . 92 6.3 Purchasing power of the wages of skilled construction workers in European cities, 1450-1913,[wages in grams of silver / consumer price index].................................... 92 6.4 Tilrkiye ve Avrupa ii1keleri imalat sanayiinde i~t;i ilcretlerinin satlD ahm giicii, 1914-1996, [Her ii1ke i~in 1914=1,0] ................. 98 6.4 Purchasing power of manufacturing industry wages in Turkey and in selected European countries, [1914­

1996, for each country, 1914=1,0]... 98 lsumer

57 Avrupa kentleri i~in tiiketici fiyat

endeksleri,1450-1913,

[Fiyatlar birim ba~ma gram

gUmii~

olarak,

Strasbourg,

1700·1749=1,0] ............................ . Chapter VI 6.2 56 ~rcent,

Page

kentlerinde

vasIf1.1 (neccar) giinlUk iicretleri, 1489-1912, [Her Yll i~in istanbul=I,01............. 82 Osmanh

BOIiim VI toman

Graphs i~~ilerin

46 goods

·1914,

Sayfa

67 daily

;:ers in

68 lskilled ld) III lkge] ... 79 ruction

l cities,

80 lskilled id) III ~-1912,

81 XIX LIST OF TABLES

T ABLO LisTESi Tablo Sayra

BOitim I

1.1 istanbul tUketici fiyatlan endeksi,

1469-1918, [1469=1,0]...................................

12

1.2 20. YUZYllda istanbul'da tUketici fiyatlan

ve enflasyon, 1914-1998.,..............................

22

1.3.1 Ge~mi~ ylliara ait parasal bUyUklUklerin

1998 ylh sonunda TUrk Lirasl ve ABD

dolan olarak e~degerleri, 1469-1799...........

24

1.3.3 Ge~mi~ Yillara ait parasal bUyUklUklerin

1998 Ylh sonunda TUrk Lirasl ve ABD

dolan olarak e~degerleri, 1915-1998

[llira=100 kuru~J...............................

BolUm II

2.1 istanbul'da glda fiyatlarl endeksi, 1469­

1914; [1469=1,00]............ .... .................

BolUm III

3.1 20. YUzydda Ankara'da tUketici fiyatlan

ve enflasyon, 1914·1998................................

BolUm IV

4.1 istanbul'da in~aat i~~i1erinin gUnlUk iicret­

leri, 1489-1922................................................

BolUm V

5.1 Ttirkiye'de imalat sanayii ticretleri 1914­

1998, [1914=1,0].............................................

BolUm VI

6.1 Avrupa kentlerinde fiyatlar ve ticretler,

1450-1913.......................................................

6.2 20. Ytizyllda Ttirkiye ve Avrupa iilkelerin­

de ki~i ba~Ina gayri safi yurti~i haslla

(GSYiH), (SatIn alma paritesine gijre,

1990 Ylh Amerikan dolanyla J.....................

Pagl

Chapter I

1.1 Consumer price index for Istanbul,

1469-1918, [1469=1,0]. ............................. .

Consumer prices and inflation in 20 th

century

Istanbul,

1914-1998.

1990

purchasing power party (PPP) US

dollars ......................................... ..

1.3.1 Monetary magnitudes of the past years

expressed in 1998 Turkish Liras and US

dollars, 1469-1799 ............................ .

1.2 1.3.2 Monetary magnitudes of the past years

expressed in 1998 Turkish Liras and US

dollars, 1801-1914 ............................ .

1.3.2 Ge~mi~ ydlara ait p

arasal bUyUkltiklerin 1998 ylh sonunda

TUrk Lirasl ve ABD dolan olarak

e~degerleri, 1801-1914.

[1 kuru~=120

ak~e] ..............................

Tables 29

1.3.3 Monetary magnitudes of the past years

expressed in 1998 Turkish Liras and US

dollars, 1915-1998 .............................

32

48

Chapter II

2.1 Food price index for Istanbul, 1469-1914,

[1469=1,0] .................................... ..

58

Chapter III

3.1 Consumer prices and inflation in 20th

century Ankara, 1914-1998 ................ ..

69 Chapter IV

4.1 Daily wages of construction workers in

Istanbul, 1489-1922 ........................... .

84

93 Chapter V

5.1 Purchasing power of

industry wages in Turkey, 1914-1

[1914=1,0] ................................................. .

Chapter VI

6.1 Prices and wages in European

1450-1913 ..................................... .

6.2 97

xx Per capita Gross Domestic Product

in Turkey and in selected [Eur'ooe:an

countries during the 20 th

purchasing power parity (PPP) as

dollars in 1990] ......................................... .

EK BOLUMUNDEKi TABLOLARIN

LisTEsi

Page

Ek

1. Istanbul,

APPENDIX TABLES

Sayfa

istanbul'da temel glda mallarmm

fiyatlan, 1469-1913 ........................

102

Appendix

1.

2. n 20 th

1990

P)

US

22

st years

and US

3.1 3.2 years

and US

fiyat

verileri

i~in

Vakdlarm Odedigi

fiyatlar, 1489-1863 ..........................

142

istanbul

fiyat

verileri

i~in

Saraym

ijdedigi

fiyatlar, 1469-1865 ........................ ..

,t years

and US

3.3 3.1

149

istanbul

3.2

32

48

20th

....... 58

1

5.1 5.2 5.3 In

....... 69

5.4 :turing

·1998,

........ 84

5.5 cities,

93

Gnp)

)pean

ntury

~ US

5.6 5.7 97

fiyat

verUeri

i~in

Narh

fiyatlan,

1520-1839........................................

164

istanbul Zahire BorsaSl'nda toptan fiyatlar, 1860-1880...................

170

istanbul

3.3

1489-1856.............. ............

142

Sources for price data for

Istanbul: prices paid by the

pious foundations, 1489-1863...

149

Sources for price data for

Istanbul: prices paid by the

palace, 1469-1865..................

154

Sources for price data for

istanbul: narh (official ceiling)

prices. 1520-1839.................

164

4.1

Wholesale prices in the Istanbul

Commodity Exchange,

4.2

Wholesale prices in the Istanbul

Commodity Exchange,

1860-1880... .............................

4.2 )-1914,

154

kaynak~a:

4.1 istanbul Zahire BorsaSl'nda toptan fiyatlar, 1884·1914 ...................

Bursa'da glda mallarmm fiyatla­

n, 1674·1864,

[Birim ba~ma ak~e ].......................

Edirne'de glda mallarmm fiyatla·

n, 1490-1864,

[Birim ba~ma ak~e J.......................

Konya'da glda mallarmm fiyatla·

n,1682-1862,

[Birim ba~ma ak~e ].......................

172

5.1

Trabzon'da glda mallarmm fiyat­

lan, 1714-1862,

[Birim ba~ma ak~e ).......................

KudUs'te glda mallarmm fiyatlarl,

1699-1866,

[Birim ba§ma ak~e ].......................

Kahire'de glda mallarmm fiyat­

larl,1624-1798,

[Birim ba~ma ak~e ].......................

170

1884-1914 ................................. .

172

Prices of basic foodstuffs 10

Bursa, ak<;e, 1674-1864......... .

174

Prices of basic foodstuffs in

Edime, ak~e, 1490-1864..........

177

Prices of basic foodstuffs 10

Konya, ak~e, 1682-1862..... ....

180

Prices of basic foodstuffs 10

Damascus, ak~e, 1643-1831.....

181

Prices of basic foodstuffs 10

Trabzon, ak~e, 1714-1862......

183

Prices of basic foodstuffs in

Jerusalem, ak~e. 1699-1866.....

183

Prices of basic foodstuffs in

Cairo, para. 1624-1798..........

184

174

5.2

177

5.3

180

~am'da

glda mallarmm fiyatlan,

1643-1831,

[Birim ba~ma ak~e ].......................

102

Prices of non-food consumption

items in Istanbul, ak<;es per unit,

kaynak~a:

29

:ers

istanbul'da

glda

dl~mdaki

mallarm

fiyatlan,

1489-1856

[Birim ba~ma ak~eJ ....................... .

kaynak~a:

~t

Prices of basic foodstuffs in

ak<;es

per

unit,

Istanbul,

1469-1913.................. ........

............. 1;

Page

5.4

181

5.5

183

5.6

183

5.7

184

XXI Ek

6.

7.

8.

Sayfa

Diger kentlerin fiyat verileri i~in

kaynak~a: Valuflarm odedikleri

fiyatlar, 1489-1866.........................

186

istanbul'da

in~aat

i~~i1erinin

gtinliik ticretleri, 1489-1922.........

192

istanbul

kaynak~a,

9.

10.

iicret verileri I~m

1489-1922.....................

AppendIx

6.

7.

8.

198

Diger kentlerde in~aat i~~ilerinin

gtinliik

ticretleri,

1489-1912,

9.

[ak~e]...............................................

202

Diger kentlerde ticret verileri i~in

kaynak~a, 1489-1912......................

205

lO.

XXII Page

Sources for price data in other

Ottoman cities, 1489-1866.. ....

186

Daily wages of construction

workers in Istanbul, akye,

1489-1922..........................

192

Sources for wage data for

Istanbul. 1489-1922...............

198

Daily wages of construction

workers in other Ottoman cities,

akye, 1489-1912....................

202

Sources for wage data in other

Ottoman cities, 1489-1912......

205