Document 10420827

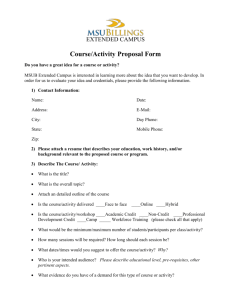

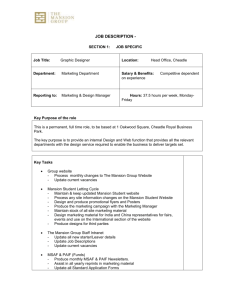

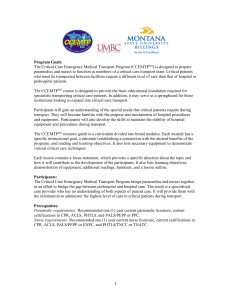

advertisement