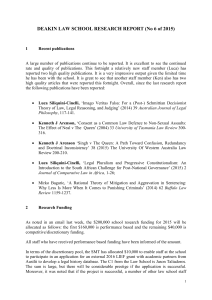

Notes pertaining to Expert Workshop

advertisement

Notes pertaining to Globalization of the International Arbitral Process: Trends and Implications Expert Workshop Tilburg Law School, 25 November, Written by Ana Delic _______________________________________________________________________________ Jamal Seifi, ‘Opening Address’ Focus of this workshop is the globalization of the arbitral process International arbitration is now the principle dispute resolution system aided by the growth of the economy, transnational trade International arbitration is multinational, multicultural Strengths of arbitration: I. brings arbitrators from different cultures to resolve disputes for different personal and economic incentives II. consensual nature III. basis for diversity IV. avoidance of static bureaucracy V. adaption of procedure to the case VI. theoretically, a democratic institution (recent exception: TTIP?) The codification and harmonization has created a common arbitration language and a common framework of laws Recourse to arbitration is in high demand Investment arbitration is a key component in the growth Recent survey on the topic revealed 90% of respondents prefer arbitration with the reasons being: enforceability of award, avoidance of the legal system, choice of arbitrators Recent developments of harmonized arbitration guidelines (Ex. International Bar Association (IBA) Rules on the Taking of Evidence in International Arbitration (1999, latest revision 2010) Greater education, training, and repeated interactions for arbitrators, which creates a common set of expectations and a convergence of norms The Jean-François Poudret and Sébastien Besson book, Comparative Law of International Arbitration (2007) highlights convergences and differences, concluding that in the past twenty five years laws are becoming identical or similar There are divergences in arbitration as well. Examples include: I. No two common criteria for arbitration II. Dissimilar ratione materiae requirements III. Divergence with regards to public policy exception (for example, common law has a specific approach while civil law has a general approach) Arbitration on the world stage: Africa: Recent keynote speech by Judge Yusuf noted the limited participation of African judges and law firms, touching on the problem of legitimacy especially in light of new bilateral investment treaties Asia: The cancellation of sixty seven older investment treaties in Indonesia between this country and the Netherlands Latin America: Prevalent view is that investment treaties are biased towards investors 1 PANEL I: Harmonization/Globalization of the Arbitral Procedure Hans van Houtte, ‘Arbitral Discovery’ Arbitral discovery is divided by legal cultures Some key differences: Common Law Civil Law All law must be presented Only relevant law must be presented Greater emphasis on oral evidence More specific rules on evidence (IBA) Rules on the Taking of Evidence in International Arbitration (1999, revised 2010) meant to harmonize these rifts However, there should be a dispelling this myth since the drafters were mostly from civil law jurisdictions (11/16 members were from civil law countries) Common law approach to written evidence spreading to civil law Yvez Dezalay, Dealing in Virtue: International Commercial Arbitration and the Construction of a Transnational Legal Order (1996) dealt with the questions: I. How should documents be produced? Tendency is to get involved with core bundle of documents and all others are to be handed in electronically II. What are the procedural aspects of document discovery? Common law tradition is that parties need to communicate all documents versus party lists all the documents required and labelling should not be too broad (basic idea behind this: know what your claim is and do not wait for the other side to substantiate your claim) American trend to go farther by hiring costly specialized firms to examine deleted emails Not producing all documents carries a negative inference in common law systems Sanitized documents are also a contentious issue since the arbitrator(s) can decide what the documents should contain but how can they make that decision without first seeing the documents? o Blurring of confidentiality o Could a third party be the answer, for instance, a document manager? Abdulqawi Yusuf, ‘Expanding Role of Appointing Authority’ Appointing authority is a topic worthy of further study EXAMPLE I: International Court of Justice and its predecessor the Permanent Court of International Justice 1923/1924, the First Annual Report of the Permanent Court of International Justice presented eight instruments (involving inter-state disputes) 1952/1953 Report presented a procedure stating the policy of the Court with regards to exercising powers to appoint arbitrators. It stated that requests to appoint arbitrators in inter-state cases were always acceded to, whilst the President ‘sometimes’ acceded to requests to appoint arbitrators in mixed public/private arbitrations. No statistics about acting as appointing authority EXAMPLE II: International Tribunal for Laws of the Sea (ITLOS) 2 Hamburg Tribunal: had an express provision about residual appointing authority in the Convention on Law of the Seas (Annex VII): o President of ITLOS shall make appointment for inter-state arbitration, if unable or if same nationality as party, appointment would be made by next senior member EXAMPLE III: Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) Rules of UNICITRAL Arbitration Rules (1976, revised in 2010): Article 6 and 11 other articles touch on designating and appointing authority and their nature/function: [I]n the event that the parties have not reached agreement on an appointing authority within 30 days following a proposal of one or more institutions or persons, one of whom would serve as appointing authority (Art. 6, para. 2); Except as referred to in Art. 41, para. 4(b), if the appointing authority refuses to act, or if the appointing authority fails to appoint an arbitrator within 30 days after receiving a party's request to do so, fails to act within any other period provided by the Rules, or fails to decide on a challenge to an arbitrator within a reasonable time after receiving a party's request to do so (Art. 6, para. 4). PCA is the appointment authority and appoints arbitrator directly in ad hoc setting Appointing authority provides certain administrative services and helps to institutionalize arbitration Statistics on this matter are available and show that from 2008 to 2014, an average of 27 requests per annum have been submitted to the PCA to designate an appointing authority Main issues emerging from an analysis of different arbitration institutions: 1. Relationship between appointing authority and parties is not clearly outlined o Article 16 of UNICITRAL Arbitration Rules provides for a limitation of liability but is this applicable to the appointing authority? 2. Different standards and functions/actions of individuals as appointing authority 3. Appointing Authority serves more than an administrative function (i.e. fees, replacement of arbitrators) o The question is whether they serve an adjudicatory function as well and thus, what are the legal parameters of this function? For example, the French Appeal Court, Supreme Court (1987) judgments clearly rejected the idea of a function beyond administration but did not address the challenges in their judgements The appointing authority plays a more active role than just appointing: has to deal with evidentiary issues, might have to examine documents, etc., if party challenges choice of arbitrator. Concluding point: extra research needs to be conducted into extra-administrative functions of appointing authorities. Stephen Schill, ‘Harmonization of Arbitral Procedure in Public-Private Arbitration’ Drivers of harmonization: national and international conventions dealing with arbitration Question which arise: o Is private-public arbitration a different field? o What is the perception of arbitrators to harmonization? Main thesis: the interaction between outside (states) and inside (arbitrators) 3 First Stage: ‘Big Bang’ event or the rise of investment treaties and the broadening of arbitration in national laws from the bottom-up o For example, the eventual lifting of prohibitions on arbitration through exceptions, specifically, with Disneyland Paris, Disney achieved in convincing the French government on a recourse to arbitration if disputes arose Investment treaties were embedded in multilateral processes => interpreted and formulated in similar ways Inside perspective: many arbitrators see public-private as no different than commercial arbitration and they are actively developing systems and substantive laws, and are following precedent o All in all, vague standards and a normative context are being created in the realm of commercial arbitration and public-private arbitration Outside perspective: based in domestic and national mainstream critique that sees arbitrators as lawmaker and thus, contrary to rule of law, equality, without constitutional basis o Harmonized responses to this critique have been coordinated and non-domestic have impacted the way that transparency is implemented and the response to intergovernmental bodies (For example, the United Nations Convention on Transparency in Treaty-based Investor-State Arbitration (New York, 2014) (the ‘Mauritius Convention on Transparency)) Arbitrators themselves react to the criticism by claiming that they are settling individual disputes and not creating a system but this argument is unconvincing and highlights the need for further transparency Questions for further interrogation: o Is arbitration a globalized system? o Should there be harmonization? o Is it more democratic to choose arbitrators? Panel II: Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and international Arbitration Norbert Wühler, ‘Opening Remarks’ In the two years since the beginning of negotiations on TTIP, discussions around it have had a significant impact on Investor State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) systems By the beginning of 2015, more than 1.5 million people had signed petitions against TTIP’s ISDS. Much of this opposition was part of general anti-globalization protests; others targeted specific features of the planned ISDS (“no secret tribunals in 5 star hotels in Washington”). This led the EU Commission to conduct a public consultation on TTIP Proposals for a modified ISDS from political and legal quarters went into the recent draft of the EU Commission for an Investment Court Concerning the wider context in which TTIP is placed, several other such agreements are being considered that provide for an ISDS system; they include: o Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which is driven by the US and excludes China, includes twelve countries of the Pacific Rim; is already signed o Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which is driven by China and excludes the US, includes the ten member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) plus Australia, India, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea: is being negotiated 4 Friedrich Rosenfeld, ‘Institutional Features of the Proposed Investment Court’ Commission proposes a new Investment Court for TTIP. The latest proposal, which was formally tabled for discussion with the U.S., dates from 12 November 2015. Institutional features: o o A Tribunal of First Instance comprised of fifteen judges (five from the US, five from a member State of the EU, and five from third States); the Tribunal shall generally hear cases in divisions consisting of three Judges (one from the US, one from a member State of the EU and one from a third country) An Appeal Tribunal composed of six Members (two from the US, two from a member State of the EU and two from third States) The composition of the divisions shall be random and unpredictable The judges will be appointed for a six-year term with the possibility of one renewal The Tribunal of First Instance and the Appeal Tribunal will be assisted by a Secretariat. ICSID and the Permanent Court of Arbitration have been proposed for this purpose. Five step procedure: 1. Consultation: to be held within three years of the date on which the claimant acquired or should have acquired knowledge of the treatment alleged to be inconsistent with TTIP or within two years of the date on which the Claimant exhausted local remedies 2. Determination of respondent: step becomes relevant where a claim concerns an alleged breach of an agreement by the European Union or a Member State thereof 3. Proceedings of first instance (all claims must be based on treatment identified during consultation phase; a provisional award shall be issued within 18 months of the date of submission) 4. Awards may be appealed (grounds of appeal can be error in the interpretation or application of the applicable law, a manifest error in the appreciation of the facts as well as any additional grounds provided for in Art. 52 ICSID Convention not covered) 5. Enforcement of Awards: (language similar to Art. 54 ICSID Convention) Some procedural particularities: o Move towards greater transparency o More regulated framework on the interplay between the new Investment Court and domestic authorities (e.g. limited fork in the road provision, restrictive provisions on jurisdiction and applicable law) o Provisions on small claims (e.g. goal of adopting supplemental rules on fees for the purpose of determining the maximum amount of costs of legal representation and assistance that may be borne by an unsuccessful claimant, which is a natural person or a small or mediumsized enterprise) o Mechanism to reduce the risk of frivolous proceedings 5 o o Confirmation of the authority to order security for costs Conclusion: the procedure is subject to increasing codification; limitation of party autonomy Further points of discussion: Is this proposed investment court really a court or a (judicialized) permanent arbitral tribunal? It is still consent-based; the proceedings are conducted on the basis of arbitration rules and result in an award. Could such investment court (negotiated on a bilateral basis) become a blueprint for a multilateral investment tribunal? Anne Meuwese, ‘TTIP’s Envisaged Chapter of ‘Regulatory Coherence’’ Procedure for producing rules: o old style (direct and sector specific) o new style (horizontal regulatory cooperation) Regulatory aspects of TTIP include: a) agreement on principles and best practices in domestic regulation (referred to as ‘regulatory coherence’; b) general (horizontal) provision concerning regulatory cooperation; and c) sectorial annexes reflecting agreements made between EU and US regulators both during/after TTIP regulations Contemporary regulation minimized future reliance on permanent regulatory mechanism Establishes regulatory body that makes annual programs US has emphasized concepts of transparency, participation and accountability; broad terms which have a level of scientific uncertainty The US has put pressure on EU to publish draft legislation and regulation on the internet for comment from stakeholders and before finalization, the EU should account for these aspects before the finalization of proposal This participatory framework is easier to do in the federal American system than in the EU The problem is that this would undermine the EU Commission’s key power to legislate, particularly, if Member States in the Council and Members of the European Parliament would be active in the consultation of the drafts that could eliminate the possibility to initiate legislation Horizontal regulatory cooperation amounts to lowering of standards and allowing lobbying groups to exert more influence, which brings into question constitutional matters and democratic legitimacy EU Commission Report brings to the fore another issue: the impact of this agreement on third parties From the perspective of regulatory analysis, this is a bilateral treaty but with multilateral consequences Concluding remark: The proposal reflects the need for a regulatory cooperation body with an annual report to follow-up and assess common priorities, a system, which is close to domestic regulatory processes Lukasz Gorywoda, ‘Shifting Balance of Power between States and Arbitral Tribunals’ Broad language of investment treaty provisions allows for discretion to arbitral tribunals and relatively unconstrained responsibility for specifying particular regulatory objectives Most favoured nation clauses and fair and equitable treatment provisions have attracted the highest number of divergent interpretations by arbitral tribunals 6 Recurring approach with recent agreement is to re-balance the power relations through the addition of language to treaties in order to clarify scope and intent of original provisions without making changes to substantive standards of protection Three techniques identified to regain re-interpretative power over treaty: 1) Use of self-judging mechanisms 2) Authority to assess the applicability of reservations and carve-outs 3) Clarification of impact of state-state determinations on investor-state tribunals All examples show shift of power between states and tribunals towards greater power given to tribunals via alternative drafting of international investment agreements Concluding questions: In examination of the arbitration procedure of TTIP, can there be an alternative reading to the procedure? Is the adoption of court-like mechanisms a necessary step in the development of arbitration procedure? PANEL III: Current and Future Trend in International Arbitration Dirk Pulkowski, ‘Converging Trends in International Investment Law’ Recent trend is transparency at the centre stage (Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), TTIP, TPP) but with some differentiation Code of conduct is desirable since it moves away from self-regulation to more binding, stateagreed format, and is evident by improved arbitration declarations Composition of arbitrators represents geographic imbalances since most are from Western countries and only 4% are Asian and 6% are African Treaty-making is not the only way to counteract abusive practices, there is also the doctrine of abusive rights, which has been used in recent case law Also there has been a lowering of environmental and health standards and all three treaties address these issues CETA only has the right to regulate in the preamble Why the convergence in horizontal organization of these international treaties? Four hypotheses: 1) Bargaining power on the part of states concluding the agreement 2) Public opinion 3) Shared legal discourse (default deference to previous awards, not formally bound to consider) 4) Institutionalization Freya Baetens, ‘The Future of International Arbitration: Will an Appellate Tribunal increase its Appeal?’ Existing post award recourse in international arbitration: For non-ICSID awards: actively seeking to have the award set aside; or passively opposing enforcement For ICSID awards: annulment applications are filed increasingly frequently; approximately one third result in a partial or full annulment even on the current, highly restricted, grounds, which begs the question, do we need judicial review to ensure quality and consistency of arbitral awards? 7 Existing appeal mechanisms and current proposals for an appellate tribunal in an international investment context are examined in light of their (1) legal effect, (2) applicable scope and standard of review, (3) nature and composition, (4) time and cost limits, and, (5) potential to reassert a balance of interests: WTO Appellate Body may uphold, modify or reverse the legal findings and conclusions of the panel; review limited to issues of law; 3 month procedure; no registration fees; collegiality Optional Appellate Rules of the American Arbitration Association (AAA): uphold or replace the award; review based on errors of law or factual determinations; 3 month procedure; parties carry fees Rendez-vous clauses in investment treaties commit the parties to the agreement to look at setting up an appellate mechanism at some point in the future (for example, CAFTA) but this has not led to the creation of an ISDS appellate mechanism as of yet. EU Commission proposal: standing Appellate Tribunal : need to revert back to original Tribunal; review based on errors of law; factual determinations (including domestic law) and ICSID annulment grounds; 9-month procedure; parties carry fees – multiple problems based on ‘merger’ of WTO Appellate Body and arbitration rules Concluding questions: how to regulate the relationship between the new appeal process and the existing review mechanisms? Is a multilateral appellate tribunal feasible and/or desirable? Gerard Meijer, ‘New Arbitration Institutes for Specialized Fields: PRIME Finance’ Panel of Recognized International Market Experts in Finance (PRIME Finance) is a specialized arbitration institute for derivatives with experts in both law and finance Other tasks: a) organizers of conferences in the field; and b) training for judges in finance and arbitration Is the specialization of arbitration a new trend? Open and accessible list of arbitrators and parts of awards may be published without necessary consent of parties in keeping with the transparency trend Party autonomy with regards choice of arbitrator via a list Choice of arbitrator procedure includes deleting arbitrators listed you do not like and ranking those you do o Is this procedure also indicative of a new trend? Emergency arbitration proceedings reflect the need for speediness The PCA will administer cases under PRIME finance rules If PRIME finance should not be around, the PCA would handle cases Costs run from 10,000 to 67,000 EUR Further Questions: Options of third party funding? o The International Bar Association (IBA) Rules on Conflicts of Interest in International Arbitration (adopted in 2014), Explanation to General Standard 6: Third-party funders and insurers in relation to the dispute may have a direct economic interest in the award, and as such may be considered to be the equivalent of the party. For these purposes, the terms ‘third-party funder’ and ‘insurer’ refer to any person or entity that is contributing funds, or other material support, 15 to the prosecution or defence of the case and that has a direct economic interest in, or a duty to indemnify a party for, the award to be rendered in the arbitration. Viktor von Essen, ‘Developing role of the ICC Emergency Arbitrator’ Emergency arbitrator outlined in Article 29 and Appendix V of the ICC Rules of Arbitration. Emergency arbitrator provisions were among the most noted of the 2012 innovations. 8 General Trend in Emergency Procedures: o 1990 ICC’s Pre-Arbitral Referee (Arts 1-7 & Appendix) o 2006 ICDR (Art 37) o 2010 SIAC (Schedule I) & SCC (Appendix II) o 2011 ACICA (Schedule II) o 2012 ICC EA Provisions (Art 29 & Appendix V) & ASA (Art 43) o 2013 HKIAC (Schedule IV) Purpose: Why force parties who choose arbitration over state courts to go to state courts for interim measures? Emergency arbitrator proceedings provide for: Special expertise of decision-maker, confidentiality, neutrality, confidentiality, party autonomy and procedural flexibility. Appointment of emergency arbitrators: impartial and independent (Art 2(4) of Appendix V); act fairly and impartially (Art 5(2) of Appendix V); statement of acceptance, availability, impartiality and independence (Art 2(5) of Appendix V); and shall not act as arbitrator in arbitration related to dispute (Art 2(6) of Appendix V) Proceedings: In absence of agreement, President shall fix place without prejudice (Art 18(1)); possibility of meetings via video conferencing and telephone (Art 4(2) of Appendix V); proceedings conducted with nature and urgency of application taken into consideration (Art 5(2) of Appendix V) Order: Not an award; written form with reasoning provided (Art 6(3) of Appendix V); does not bind the arbitral tribunal with respect to question, issue or dispute determined in the order (Art 29(3)). A priori outside the scope of the New York Convention 1958. Indirect enforcement mechanisms such as emergency relief at the national levels Types of measures sought: 1) Securing enforcement of the future award (Freezing assets); 2) Preserving or restoring the status quo (Preventing aggravation of damages); 3) Anti-suit injunctions; 4) Interim payments. Test to be satisfied to obtain relief: o Article 29(1) ICC Rules: Urgency requirement. o And: prima facie case or reasonable chance; harm that can be compensated; serious or irreparable harm; and harm to applicant outweighs potential harm to respondent. o Not all emergency arbitrators applied all the above criteria. The growing importance of interim relief leading to the facilitation of a settlement despite doubts about enforceability Concluding question: Is there a general trend towards the same test to be satisfied to grant emergency measures? 9