Communication with Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities and Psychiatric Disabilities:

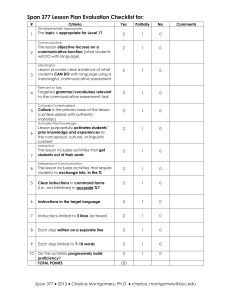

advertisement