ALLOWING ACCESS TO SUPERANNUATION FOR HOUSING A Discussion Paper

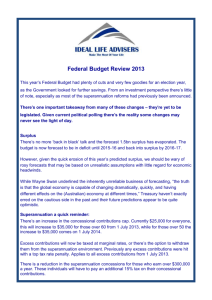

advertisement