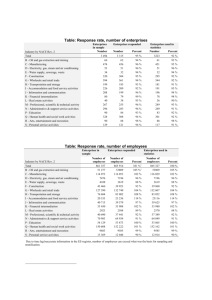

TD Trade and Development Board

advertisement