An Overview of Guatemala’s Medical Tourism Industry Version

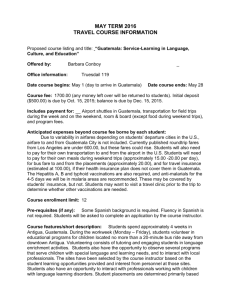

advertisement